Taken from a distant country:

the girls from Salonika in Ravensbrück1

By Stefania Zezza*

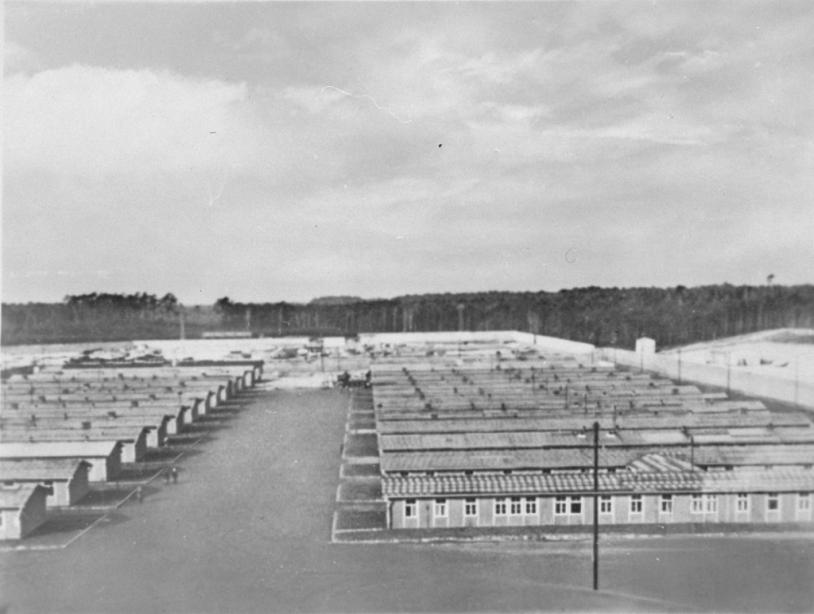

Exterior view of barracks at the Ravensbrück concentration camp between May 1939 and April 1945. USHMM archives.

The history of the Jewish community of Salonika during the Holocaust and, more in general, that of the deportation of the Jews from Greece, have not been studied as deeply as the fate of other Jewish communities. Specific research has been done and excellent works focused on Sephardim have been published only during the last decades, nevertheless the Jews from Greece and from Salonika, the city where the majority of them lived, were originally mentioned and remembered by many survivors already in their memoirs in the late 1940s and 1950s.

The men and women from Greece stood out among the prisoners in the camps for their particular characteristics and in the Auschwitz Birkenau complex they constituted what Primo Levi defined as the most civilized national nucleus. The girls from Salonika, especially, the few of them who managed to survive the first selections, were remembered for their beauty, their singing, their exotic features, but also for their skills, their language issues and their kindness. While many accounts and studies focused on the situation of men, only a few have dealt with the women from Salonika.2 Their fate in the Auschwitz Birkenau complex, during the evacuations and in the camps in Germany, deserves to be studied more in depth by focusing on their perspective and their testimonies. In particular it is interesting to examine their fate in Ravensbrück and its sub camps, which were their final destination after the evacuations in the winter of 1945.

In the spring of 1943 the Greek transports began. Greece overflowed Birkenau with her rich individuality. Greek women brought with them the exotic beauty of their sunny country. Their violent speech breathed the rhythm of seaboard cities, incomprehensible, sounding like running water, the noise of the ports. In the hubbub after roll call it overruns all the other tongues. Their tawny bodies, sometimes very beautiful, have been clothed in the tatters of old army uniforms. Their hair has been cut.

During the long trip from Salonika to Oswiecim they had become infested with lice and boils. None of the transports which has arrived in Oswiecim up to now had as many lice as the Greek women.3

With these words in 1947 Seweryna Szmaglewska, a Polish political prisoner, remembered the Greek women and devoted many pages of her memoir to them. She wrote about Alegri, the fifteen year old girl, who could sing well and used to sing sad songs: she was portrayed by the writer as a symbol of those girls who died in Birkenau as a result of the harsh living and working conditions, in her case in the Fischerei, the ponds near Harmeze.4

Only a few girls from the Greek transports managed to survive until January 18th, when the evacuation of Auschwitz and their odessey began. The Nazis then evacuated them to the camps in Germany in order to be exploited as forced laborers in the German factories. At the time of the liberation, in spring 1945, they found themselves deprived of any point of reference. One of them, Rita Benmayor, was interviewed by David Boder5 in Paris in August 1946. The psychologist recorded more than one hundred interviews on a wire recorder as part of his project and study on trauma. They represent some of the earliest oral documents about the Holocaust. Rita had been deported when she was 16 and was liberated in May 1945, when she was 19 years old. Her story, which can be heard in Boder’s original recording,6 is similar to the stories of other girls who had been taken to the camps from a distant country.

“They took away the best years of our life”: these are the words which can be constantly read or heard in the later testimonies given by these young women who were deported from Salonika to Auschwitz Birkenau in 1943 and then were evacuated to Ravensbrück in 1945. They were the remnants of the Salonikan women who had arrived at the camp during the spring and summer 1943. On average they had spent two years in the concentration camps while they were teenagers or in their early twenties. During the Holocaust they had lost the majority of their relatives and at the time of the liberation they were mostly alone.

Lola Seror Putt’s experience is extremely meaningful from this point of view. In a video interview given to the USC Shoah Foundation on November 27, 1996, she repeatedly talked about her feelings of loss and grief, which had accompanied her all of her life. Born in 1926 in a middle class Salonikan Jewish family, she was deported with her parents and three siblings to Auschwitz by the transport which arrived on March 25, 1943. She was the only one in her family who survived the deportation and the camps. Her older sister had escaped the deportation and lived in hiding in Greece for two years. Lola was then 17 years old and, above the terrible sufferings she underwent and could see inside the camp, she felt deprived of what a young girl needed most: a family, freedom, the opportunity to live a normal life.

“It was too much, it was too much for me,”she said.7 All the girls from Salonika who gave their testimony, both earlier and later, share this same feeling of loneliness and loss: the majority of them never went back to their hometown, where nobody was waiting for them and nothing of their previous life was left.

Rita Benmayor told David Boder: “I am left alone from the whole family… I did not want to go to Greece, why, I had no family . . .And I [would be] all alone in . . . In Greece . . .[If] I went to Greece, see my house without my mother, without father, I cannot see that . . .”8

The Jewish Community in Salonika was almost completely annhilated during the Holocaust: the percentage of losses had been among the highest in Europe: about 90% of the Salonikan Jews were murdered.

It was one of the most tragic events of the Holocaust: the loss of the largest Sephardi community in the world. The peculiarities and features of the Salonikan Jews, who at the end of the fifteenthcentury had moved from Spain to the city, then under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, made them quite recognizable and different from the majority of the prisoners in Auschwitz Birkenau. When Frieda Medina Kovo arrived with her family at Auschwitz Birkenau on April 13, 1943, she saw for the first time some Hassidim who were taken to the gas chambers. She remembered that she could not understand who they were. She told the interviewer of the USC Shoah Foundation that she had never seen in Greece Jews who wore black hats and garb, and also had long side curls.

Frieda was later deported to Ravensbrück, where she was evacuated, and her name may be found in the list of the January 23th, 1945 transport, which is one of the few existing written documents available about Ravensbrück.

The evacuations from the camp had began as a result of the approaching advance of the Red Army: the largest of them took place on January 18, 1945, when about 60,000 prisoners were moved to the camps inside the Reich to be exploited as slave laborers. Many of them died en route, some got to their destination after days, or weeks, walking on the icy roads or travelling in open wagons, without any food or opportunity to rest.

The prisoners were transferred, chaotically, to camps which had not been originally set up to lodge more than a few thousands prisoners, and where the living conditions became even more unbearable due to the influx of thousands of people and the consequent overcrowding.

Ravensbrück, a camp established for women in 19399, was one of the destinations where the evacuated prisoners, mostly women in this case, were sent.

In January 1945 the camp looked very different from what it had been at the beginning and in the following phases: the number of arrivals drastically increased in 1944 and 1945, when approximately 100,000 prisoners were deported there from other camps or occupied countries. The number was almost ten times bigger than that of the deportees who had arrived to the camp in the previous four years. Located in the woods alongside the lake Schwedt, in the proximity of Füstenberg, Ravensbrück began functioning on May 12,1939, when the first 867 prisoners were transferred there from Lichtenburg: they were German, Austrian political prisoners or Jehovah’s Witnesses, some of them were also Jews arrested for political reasons. From then on the conditions inside the camp, the origin of the prisoners and the events of the war shaped its features. In 1939 the small number of prisoners allowed the existence of acceptable living conditions, in 1940 and 1941 the arrival of thousands of Polish women, and later Russians, brought about a change in the camp’s population: the Poles constituted the majority of the prisoners for a long time. In 1942 the Jewish women were murdered as part of the implementation of Action 14f13, or they were sent to other camps in the East, since Germany, according to Hitler’s aim, had to be Judenfrei. In 1944 the arrival of the French political prisoners changed the features of the camp’s population once again. Thousands of Jewish women were sent to the camp again only between the end of 1944 and in 1945.

It is in this final phase, that is from late autumn 1944 to April 1945 that the majority of the Greek women arrived at Ravensbrück. Eleven of them are registered in the list of transport no. 42 from Auschwitz Birkenau,10 some others, whose names are not present in the few lists which were not destroyed, gave testimony about their deportation and imprisonment in the camp after the war. The analysis of both the 23 January list and the written and oral testimonies can provide interesting information on the Sephardi women from Greece in Ravensbrück and on their particular situation in comparison with that of other prisoners deported from other countries. The eleven women’s average age was 22, the oldest was 23, the youngest 17.

Unlike the majority of Ravensbrück prisoners coming from other countries, the Greek women were not deported to the camp directly from their country of origin. They were taken there after being kept in Auschwitz Birkenau for about 20 months, and for many of them this was only a step to sub camps like Rechlin/Retzow, Malchow or Neustadt Glewe. Actually, Ravensbrück was the center of a system of 40 sub camps, which were established for female prisoners in different areas of Germany. Those closer to the main camp, about 20, stayed under Ravensbrück’s jurisdiction until the liberation, the others were handed over to geographically closer camps in summer 1944.

There is no evidence documenting the presence of Greek women in Ravensbrück before their arrival during the evacuations.

The first big group of Greek women arrived in late October 1944.11 Karolina Lanckoronska, a Polish prisoner wrote in her memoir:

In the late autumn a transport of some fifty Greek women arrived. It was a troublesome situation, because they knew no language but their own. We were struck by the way they pointed out the P on our sleeves to one another. They behaved very cordially towards the Poles, but in a respectful and disciplined way. They appeared to be rather simple women, with the exception of one whose orders they obeyed like lightning. Her name was Sula and she was a nineteen-year-old law student from Salonika… Later we learnt that she was the commander of a small military unit, captured, fully armed, in the Greek mountains. Sula was also their interpreter because she was said to 'know' French.12

Soon these Greek prisoners were transported to another camp.

The Greek women left Auschwitz Birkenau on January 18th in different transports which ended up in Ravensbrück. From the analysis of their testimonies and documents it is possible to outline some key elements and general patterns. They were mostly young women who had survived the first selection at their arrival in Auschwitz, when older women were all murdered. The percentage of losses in the transports from Greece was extremely high because the camp was overcrowded and new crematoria were being put in function at the time of their arrival, that is, in the case of Salonika, spring and summer 1943. Also many of those who had been considered able to work and entered the camp, died like flies, as the survivor Kitty Hart remembers. They suffered for the cold Polish weather and in the majority of cases couldn’t communicate in German, Polish or Yiddish.

As Maria Ossowski, then a young Polish woman, remembers:

The misfortune of the Greek girls was that they didn’t know any other language than Greek; they couldn’t speak Yiddish or German, and that made their life a double misery because you had to understand what all the shouting was about, and the shouting was all in German. I remember they were still quite lovely because they were fresh arrivals in May 1943 and they were singing beautiful songs. They didn’t last long, not only the lack of food and hard work, but the climate took its toll and they perished extremely, extremely quickly.13

The situation can be easily understood if the list of the August 21, 1943 selection in Birkenau is considered. On that day a big selection for the gas chambers was carried out in the women’s camp, 498 women were selected by the SS and by Maria Mandel, among them 438 were Salonikan Jewish women arrived in the previous three or four months. They had already become unfit for work, as had those who had arrived in May.

The girls who were later evacuated to Ravensbrück had managed to survive, as can be understood from their testimonies, mostly because they had been working indoors. Some of them had also beenexperimented upon for sterilization in Block 10. Even though survival in the camps didn’t actually depend on explicit rules, the opportunity to work in the Canada Kommando, in the Schue Kommando or in the Union Fabrik made the difference in the Polish climate, especially for people accustomed to much warmer temperatures. As Rita Benmayor said to David Boder, in Auschwitz Birkenau:

The first month, three month[s], I worked at the road, through road, eh, did stones . . . And then I was in the shoe detail, I repaired shoes, I was [in] the shoe detail . . . I was one year in the shoe detail.14

These young women had been deported in spring 1943, mostly between March and May. Their registration numbers are important for understanding precisely when they arrived.15 Often small groups of relatives (sisters, cousins) and friends arrived together at the camp and supported each other from the beginning for a long time, sometimes till the liberation.

Annette Florentin Cabelli16 (n. 40637) arrived with her mother, siblings, aunts and cousins on April 10, 1943. She stayed with her cousin Laura Amir until they were both sent to work in the Revier. She worked as a door warder in the typhoid block, while her cousin died in the dysentery block.

All the testimonies agree on the great importance of mutual help both in Auschwitz-Birkenau and in Ravensbrück and its sub camps. In the case of some Salonikan girls, they also befriended the French women, with whom they could communicate. Many of them had in fact studied at the schools established in Salonika by the Alliance Israëlite Universelle, where they had learnt also to speak French.

For instance, Lisa Pinhas (n. 41117), who had been deported to Auschwitz on April 13 1943, could stay in touch and work with her sister and cousin, some friends, and also a French girl deported from Marseille, Annette Amouch. The relations among the Greek women were very close, and their knowledge of French made it easy to communicate with the French prisoners.

In April 1945, when she was put into the block of the French prisoners in Ravensbrück, Lisa talked to one of them who asked her

- Vous êtes française?

- Non, je suis grecque.

- Tiens, on parle si couramment le français en Grèce?

- J’ai fait mes études dans une école française en Grèce.17

Frieda de Medina Kovo18, one of the girls in the January 23 list, managed to stay together with her sister and some friends. When they were sent to work in the Kanada, she lived in Block 27 and shared her bed with Desi Barzilai (later de Kalderón), who after the war moved to Chile, and Stella Aruch who later went to the United States. They spoke Ladino among themselves, but Frieda was fluent also in French and could speak German. She contracted typhus but managed to avoid the selection of August 21, 1943. Due to her language skills, she was later transferred again to work indoors: as she said, she was in charge of registering the train trucks. She was evacuated on January 18, marched to Breslau and was put on a train. Half of the prisoners were left in Bergen-Belsen, the others, among them Frieda, got off the train at Ravensbrück.

Lisa Pinhas also worked in the Kanada Kommando and later, when the transports were less frequent and the number of workers in the kommando was reduced, in the Union-Fabrik. After the doctor who had protected her had been sent away and she had been kicked out of the Revier, Annette Cabelli also managed to be sent to work in the Union Fabrik, thanks to the help of Mala Zimmembaum, a girl from Belgium who was an interpreter inside the camp and with whom she spoke French.

On January 18, 1945 all the girls working there were forced to march to Auschwitz 1 from where they were evacuated.

Lisa Pinhas wrote:

C’était environ vers les 5 heures de l’après- midi; on nous intima l’ordre de nous tenir prêts à partir car on aurait évacué le camp le soir même. On ne peut pas facilement imaginer la folie qui s’empara de nous tous. Hommes et femmes s’embrassaient en pleurant de joie, de crainte, d’incertitude. Se reverrait-on jamais? On échangeait des paroles d’encouragement, conseillant d’être forts devant l’épreuve à subir afin de se revoir un jour. L’émotion nous égarait. Jacques Strumza vint embrasser une dernière fois sa sœurette en me la confiant. Instants inoubliables!...19

Le froid et le vent avaient redoublé de violence. Sous les rafales de neige, sous suivions la colonne interminable ; nous avions peine à avancer, à respirer et nous glissions très souvent. Chaque pas demandait un effort surhumain, nos jambes s’alourdissaient de plus en plus, nos pieds engourdis s’enfonçaient lourdement dans la neige profonde.20

Palomba Allalouf on the day of the evacuation met another girl from Greece, Frieda, and together they left. They supported each other:

Three nights and three days… The two of us had a blanket, a bit of bread and a bit of sugar. I told her to hide under the blanket and that we are not going to speak to anyone, we will eat a bit of bread, a bit of sugar to stay alive. …Schnell, schnell, the dogs, the Germans… We took each other’s hands. We were on our own, the only two Greeks.21

Also Lisa Pinhas remembers that she walked together with three friends, Bella Stroumsa, Annette Amouch and Anna. They helped each other during the march to Ravensbrück which lasted four days and five nights: they walked to Breslau, then were put onto open wagons and passed through Frankfurt-on-Oder and Berlin before getting to their destination. They managed to survive thanks to their mutual support and to their friendship with some French women.

Also Lisa Pinhas remembers that she walked together with three friends, Bella Stroumsa, Annette Amouch and Anna. They helped each other during the march to Ravensbrück which lasted four days and five nights: they walked to Breslau, then were put onto open wagons and passed through Frankfurt-on-Oder and Berlin before getting to their destination. They managed to survive thanks to their mutual support and to their friendship with some French women.

When in the middle of the night they arrived at a camp, they didn’t know where they were, they were forbidden to enter the barracks and had to lie in a courtyard. There they met other friends and relatives, who had been evacuated from Birkenau and had arrived earlier. Lisa Pinhas met her sister Maria and Mini Avayou, who had worked with her at the Kanada. During the night they were forced into a big barrack and they eventually found out they were in Ravensbrück.

All the witnesses agree on the overcrowding and the lack of water and hygiene they found in the camp. In Ravensbrück, Anna Florentin Cabelli said:

There were people from different backgrounds and confessions, but the conditions of that camp, which were already bad, worsened ostensibly with the arrival of those who came from Auschwitz. For 8 or 10 days we observed how the Germans were becoming fewer and more concerned about destroying papers and leaving no trace or evidence than to organize us for work. And of course, the food was still scarce. We became real unscrupulous beasts with food. Food was often wasted by the struggle that was fought for it. From there, shortly afterwards and in the same deplorable conditions, they moved us to the Malchow lager.

Palomba Allalouf also remembers: “We had arrived in Ravensbrück… it was very dirty… we were hungry and we had no food.”22 The overcrowding was the main problem in the camp and caused epidemics, “There were five people sleeping in one bed…we had so many lice,” remembers Rita Benmayor.

The hygienic conditions were the worst possible, as Lisa Pinhas remembered

Mais l’unique Block des water-closets était continuellement embouteillé tellement il était peuplé de dysentériques… D’ailleurs, à l’intérieur, l’air était irrespirable et on pataugeait dans les immondices des autres jusqu’aux chevilles ; c’était affreux. Vraiment, on ne peut pas décrire les choses. Donc, il était exclu d’entrer dans le Block des toilettes, il ne fallait même pas y penser. On préférait alors un coin de la cour. Cette opération effectuée en plein air devenait un véritable supplice, car le froid était devenu intolérable et nous n’avions pas de vêtements pour nous protéger de ses cruelles morsures. Je me demande comment nous n’avons pas perdu la raison en ces jours de cauchemar.23

Only after some days the prisoners who had arrived together with Lisa Pinhas got their numbers and were admitted to a block where they could find a place to sleep. According to Pinhas’registration number, 99575, she arrived at the camp between January 20th and 23rd, since the numbers registered on the first day were from 97693 to 97774, and those registered on the twenty-third were from 101577 to 102304. It was in this group that eleven Greek girls, present in the list of the transport from Auschwitz, were given their numbers. They were Daisy24 Alchanati (101647), Sara Asael (101667), Bella Rason (101765), Estella Arouch (101766), Bella Ziko (101767), Bella Kapon (101771), Alegry Löwe (101772), Ester(sch) Chasi (101773), Frieda Medina25 (101827), Desi26 Barzilai (101828), Ester Macyl (102259). Some of the names in the list are spelled incorrectly, but their registration numbers in Auschwitz and other testimonies made it possible to understand what the correct spelling was.

Like many other prisoners, among them the Greek girls, Lisa and her group of friends were sent to one of the subcamps after some weeks, in February.

From 1944 on, the use of female labor in the Ravensbrück camp complex had become more and more intensive. At that time, at least every second prisoner who was taken to the Ravensbrück camp was taken to one of its subcamps. Ravensbrück became a gigantic transit point for the deployment of labor in the subcamps.27

Palomba Allalouf and Frieda, like Annette, were sent to Malchow:

One morning after eight days they told us Zählapell, Zählapell... We all were outside and a German came: you out, you out. Frieda and I were among the ones he called out. They put us in a bus…28

The destination of Lisa, Rita Benmayor and some others was Rechlin/Retzow, an airfield and Luftwaffe testing site located close to the Lärz airport. Women had began being transported there in July 1944, they were exploited in excavation and construction work. From autumn 1944 on they had to build camouflage pits to hide the aircrafts or to clear the site after the bombings.

C’était au mois de février. Nous travaillions alors dans les forêts ou les camps d’aviation, à creuser des fosses, à couper des branches d’arbres pour camoufler les avions.29

Since more and more prisoners were taken there as a result of the evacuations, the women who arrived were lodged in the large barrack formerly used as a cinema. The living conditions were extremely harsh due to the overcrowding, the reduction of rations and the epidemic caused by the lack of hygiene. This was the situation the Greek women had to face in the camp when they were transported there from the main camp. “In Retzow, it was not good, there was nothing to eat, we had soup once and a little piece of bread to eat…Many people died from hunger.”30

Lisa Pinhas, who suffered from dysentery, remembers the conditions inside the camp and the Cinema barrack where the recently deported were gathered:

La saleté, la faim, l’épuisement et les maladies faisaient tous les jours de nouvelles victimes. Ainsi la mort arrivait-elle à grands pas dans ce lieu maudit où toutes les maladies infectieuses s’étaient donné rendez-vous et prenaient des proportions inquiétantes.31

There were weekly selections: women considered unfit for work were sent back to Ravensbrück and murdered in the newly functioning gas chambers. Lisa Pinhas managed to escape this fate thanks to the help of other prisoners. In March 1945, for about one month she was kept inside a block, together with other inmates, they were not allowed to go outside except for the rollcall. The living conditions there were unbearable. After they got back to work in the woods, a devastating bombing destroyed the airfields on April 10, therefore they were forced to clear the ruins. After a few days some of the prisoners were taken back to Ravensbrück, where the Greeks stayed in the block of the French. They worked in what Lisa Pinhas calls ‘paplans’32 dans le Kommando Kanada de Ravensbrück. They had to carry outside filthy mattresses, blankets, pillows and leave them under the sun.

Frieda Medina Kovo was at Ravensbrück for some weeks and remembers the harsh living conditions: there were no shoes to wear for the majority of the prisoners, the food there was rarely distributed. After a few weeks, spent inside the tent in the camp, she was transported to Neustadt Glewe, Meklenburg. On September 1,1944, this sub camp had been established to provide a workforce to the Dornier Works at the military airfield in the proximity of Neustadt-Glewe, district of Ludwigslust (Mecklenburg). In the last phase of its activity, from February 1944 to April 1945, the number of inmates increased from 900 to approximately 5,000: they were mostly Jewish women evacuated from Auschwitz Birkenau and transported there from Ravensbrück.

The Neustadt-Glewe camp prisoners, who were already dangerously enfeebled by their previous sufferings and the death march, lived in disastrous conditions. The women were crowded into unheated storage rooms, factory halls, and barracks. There was hardly enough room to sleep, and the hygienic facilities were completely inadequate. The majority of the women suffered from undernourishment and disease. Some of the most severely ill were taken “back” to Ravensbrück on trucks.33

They worked in the airfield as well as in the Dornier workshops and in digging and construction. Frieda was assigned to camouflage the airplanes. She remembers that on April 23, 1945, the airport was heavily bombarded and the girls hid in the woods which were burning like the airfield. On May 2, the guards locked the prisoners inside the barracks and left the camp. Maria, a Greek friend of Frieda, who was strong enough, broke the window bar. They went out and understood that the Germans had left. In the afternoon the Russians entered the camp.

On April 27 the evacuation from Ravensbrück had begun. Lisa Pinhas remembers:

Toutes les Grecques, nous marchions en un groupe séparé; nous faisions des projets pour les jours à venir. Les chrétiennes pensaient à la joie des parents lorsqu’elles rentreraient chez elles, tandis que nous, la tête basse, le cœur en deuil, nous gardions le silence. Un problème très grave se posait pour nous avec la fin des camps. Avec la liberté naissait en nous la peur, une peur pire que le crématoire : la peur de rentrer dans une patrie où personne ni rien ne nous attendaient plus. Non, plus personne.34

They arrived at Malchow on April 28:

À la nuit tombante, nous arrivâmes à Malchow. On nous fit entrer dans le camp où déjà d’autres prisonnières étaient assises avant nous. On nous jeta pêle-mêle dans une salle immense. Quel chaos, mon Dieu ! On se disputait, on se battait pour avoir une petite place par terre.

On mourait littéralement de faim dans ce camp.35

Rita Benmayor was sent to Malchow, directly from Retzow though. There she stayed until the Germans left the camp when, together with some other prisoners, she went to the village looking for food. When the Russians arrived, they went back to the camp “and the Russians gave us much to eat, we fixed ourselves up, we had soap to wash . . . They were good to us.”36

Lisa Pinhas and other Greek women had instead been evacuated from Malchow, they walked in the woods controlled by SS guards. She remembers an event that occurred to one of the eleven girls of the January twenty-third list, Daisy Alchanati:

Soudain, une Frau SS, un vrai monstre de laideur et de cruauté, lança son chien sur une jeune fille grecque de 19 ans, Daisy Alhanaty, en lui ordonnant de la mordre.37

Daisy was born in Salonika on January 28 1925, and she had arrived in Auschwitz on April 19, 1943. The dog injured her severely but she managed to walk with the help of her friends. At night the SS disappeared and the women found themselves alone. Among them were the eleven Greek girls.38 They were confused and didn’t know what to do but kept on walking; in the next days they met Russians, Italians, and prisoners from the camp, including Daisy, whom they had lost in the crowd of prisoners and whose wound had been treated by the Americans she had run into.

The war was over, they were free.

* Stefania Zezza is a teacher at Liceo classico Virgilio in Rome and a researcher. Graduated from the International Master on Holocaust Studies (Roma Tre University), she collaborates with it. This article is the result of a study on testimony and translation presented at the workshop on this topic at the Wiener Library in London in November 2015. She has recently completed research on the fate of the Salonikan Jews during the Holocaust, focusing also on the early testimonies and the work of David Boder: “With their own voices: the interviews of David Boder with the Salonikan survivors”. Her current research interests include the relation among trauma, memory, testimony and language.

References

Kounio Amariglio, Erika. From Thessaloniki to Auschwitz and Back.

London: Valentine Mitchell, 1998.

Bernadac, Christian. Le camp des Femmes Ravensbrück.

Neuilly-sur-Seine: Michel Lafon, 1998.

Blatman, Daniel. The Death Marches, Cambridge, Mass. and

London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2011.

Bowman, Steven. The Agony of Greek Jews, 1940-45. Stanford:

Stanford University Press 2009.

Caplan, Jane and Nikolaus Wachsmann (eds.). Concentration Camps in

Nazi Germany: The New Histories, New York: Routledge/Taylor &

Francis e-Library, 2009.

Fleming, K. E. Greece: A Jewish History, Princeton , NJ:

Princeton University Press, 2008.

Lanckoronska, Karolina. Michelangelo in Ravensbrück: One

Woman's War against the Nazis,(translated from the Polish by Noel

Clark): Cambridge, Ma, Merloyd Lawrence / Da Capo, 2008.

Levi, Primo. If This Is a Man: The Truce. Translated by Stuart

Wolf. London: Abacus, 2013.

Lewkowicz, Bea. The Jewish Community of Salonika: History, Memory,

Identity, London/ Portland: Valentine Mitchell, 2006.

Mazower, Mark. Salonica, City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and

Jews, 1430-1950. London: Harper Colllins, 2004.

Novitch, Miriam. Le Passage des barbares : contribution à l’histoire

de la déportation et de la résistance des Juifs de Grèce, 2e

édition, Israël: Ghetto Fighters House Publishers, [1re éd. en français,

1967, Paris : Presses du Temps Présent],1982.

Philipp, Grit. Kalendarium der Ereignisse im

Frauen-Konzentrationslager Ravensbrück 1939-1945, Berlin: Metropol,

1999.

Pinhas, Lisa. Récit de l’enfer Manuscrit en français d'une Juive

de Salonique déportée, Paris: Edition Le Manuscrit, 2006.

Szmaglewska, Seweryna Smoke Over Birkenau. Translated from the

Polish by Jadwiga Rynas. Chicago, Il: Pickle Partners Publishing, 2015.

(Text originally published in 1947 under the same title.)

Smith, Lyn. Forgotten Voices of the Holocaust, London: Ebury

Press, 2006.

Tillion, Germaine. Ravensbrück, Paris: Points, 2015.

Tomai, Photini. (Hellenic Ministry of Foreign Affairs), Greeks in

Auschwitz-Birkenau, (translation by Alexandra Apostolides), Athens:

Papazisis Publishers S.A. 2009

Varon‑Vassard, Odette. ”Voix de femmes,” Cahiers balkaniques [Online],

43 | 2015, Online since 25 July 2017. URL :

http://journals.openedition.org/ceb/8528 ; DOI : 10.4000/ceb.8528

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and

Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. I, Bloomington and Indianapolis: published

in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Indiana

University Press, (Kindle edition), 2009

Websites

This article is the result of a research study the author has been engaged in over the last two years and that is still ongoing.

2 The number of memoirs written by male Salonikan survivors is much higher than that of those written by women. Among the latter, the most important are: Lisa Pinhas, Récit de l’enfer Manuscrit en français d'une Juive de Salonique déportée, Paris: Edition Le Manuscrit 2006; Erika Kounio Amariglio, From Thessaloniki to Auschwitz and Back, London: Valentine Mitchell 1998.