A Moroccan Jewish Family Saga in Two Volumes:

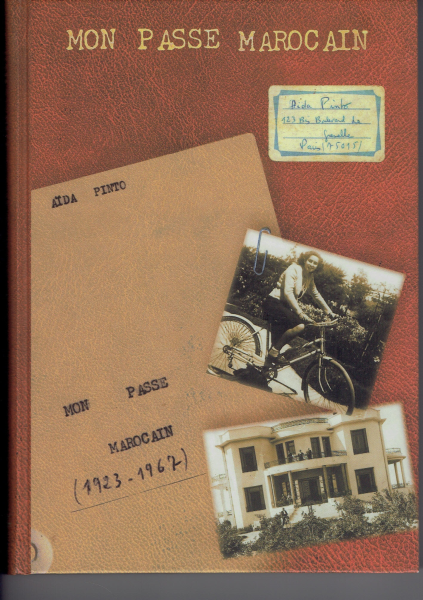

Aἲda Pinto. Mon Passé marocain [My Moroccan Past]. Jerusalem: Abraham Albert Cohen Editions Erez, 2004.

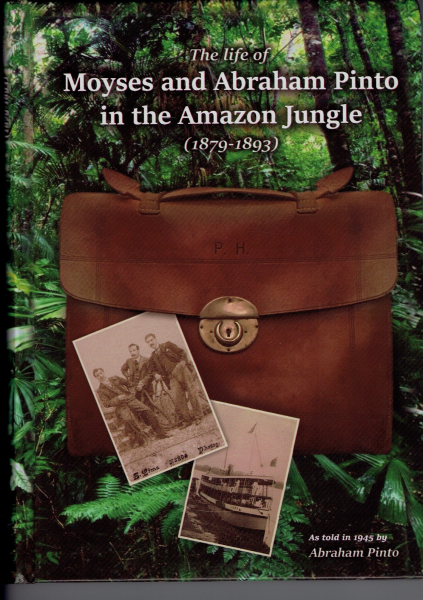

Abraham Pinto et al. The Life of Moyses and Abraham Pinto in the Amazon Jungle. As Told in 1945 by Abraham Pinto. Abraham Cohen Erez Publishing, 2017.

Reviewed by

Judith Roumani *

These two books are private publications by the Pinto family and explicitly state that they are not published for commercial purposes. They are truly fascinating, though, so I felt it would be of interest to Sephardic Horizons readers to learn about them.

The second book, published in 2017, relates to the earlier history of

the Pinto family of Tangiers so I will begin with that one, even though

it was published much more recently. It is presented in this volume in

four languages: Spanish (the language originally used in the family),

French (the language they gravitated to after receiving French-language

Alliance school educations in Morocco), Hebrew and English (more recent

additions for the far-flung contemporary members of the extended Pinto

family). This account (as told in 1945, edited by several new-generation

Pintos) relates how the family rose from poverty (the original nuclear

family lived in two rooms under a synagogue in the Old City of Tangiers)

to join the wealthy class of Jewish Tangiers, constructing two

magnificent twin villas on the outskirts of the city.

The second book, published in 2017, relates to the earlier history of

the Pinto family of Tangiers so I will begin with that one, even though

it was published much more recently. It is presented in this volume in

four languages: Spanish (the language originally used in the family),

French (the language they gravitated to after receiving French-language

Alliance school educations in Morocco), Hebrew and English (more recent

additions for the far-flung contemporary members of the extended Pinto

family). This account (as told in 1945, edited by several new-generation

Pintos) relates how the family rose from poverty (the original nuclear

family lived in two rooms under a synagogue in the Old City of Tangiers)

to join the wealthy class of Jewish Tangiers, constructing two

magnificent twin villas on the outskirts of the city.

One has to admire the courage and drive of two brothers (a third one, Mimon or Mauricio, died soon after arriving in the area) who risked their lives to make good in the Amazon region during the rubber boom of the late nineteenth century. They risked so many dangers that the account, reported to be absolutely faithful and accurate, becomes a hair-raising adventure story. Common dangers were jaguars hunting at night (a fire had to be constantly burning to deter them, with guards at the ready with guns), stampeding herds of wild boar, boa constrictors swimming in the lakes and crawling into the forest, cannibals, quicksand, electric eels, Indian tribes with arrows, political confrontations between Brazilians and Peruvians, and, not least, canoes and steamboats that would sometimes sink. After describing the sinking of one steamer he was sailing on, and after describing his years of adventures as a trader moving about by canoe, Abraham Pinto casually mentions that he actually did not know how to swim!

These brothers had had absolutely no training for their chosen profession: they learned on the job how to canoe from one small Amazonian port to another in their quest to trade. They started small and only gradually began to participate in the rubber trade which was then growing tremendously due to demand for rubber tires for the first cars. Living extremely frugally off the land, and both reinvesting their profits and sending about half of them back home to Tangiers, they imported goods made in England and elsewhere and sold them on the upper Amazon and its tributaries. Though deeply attached to each other, they would separate for many months at a time, trading on different rivers, until they would meet again for Yom Kippur:

Many times while on the Jurua (river), even when we were months’ distance apart, he in one canoe, me in another, we would always write each other to plan where to meet for Yom Kippur. When we finally met, our rowers would build a hut in some removed spot in the woods and light fires that they would tend through the night to ward off snakes and wild creatures. With our canoes secured to the banks, our helpers stood guard each with Winchester in hand ready to shoot any beast that wandered too close. One time our guards killed a jaguar that came near the hut; but even this did not take us away from our prayers (p. 229)

After about a decade of this strenuous and dangerous life, Abraham decided to retire from it and set up a shop or trading post in Iquitos. Their successes were due not only to their business acumen and courage but also to their engaging personalities and their absolute trustworthiness. Operating often with credit for large sums, they always reimbursed their clients and extended trust generously to others. Abraham’s reliability and honesty earned him great respect and at the same time success. He always thanked the Almighty for maintaining him in good health, saving him from so many dangers, and bringing success to his efforts, which lasted fourteen years in the Amazon. Though Abraham did not wish to see his memoirs published, his grand-nephews and nieces, asking his pardon, have done so as a memorial both to him, who died childless, and to his siblings, their own grandfathers and grandmothers, who did not manage to write their own.

The second book, Aïda Pinto’s memoirs, Mon Passé marocain,

published in 2004, covers almost a century of family history from two

generations later, up to the end of the twentieth century. It describes

more tranquil lives, fortunately hardly affected by the war and the

Holocaust, and seriously disrupted only by the independence period in

Morocco, when the majority of Morocco’s Jews, including most of this

family, over time sought more secure shores. The Pinto family initially

lived in the two villas originally outside Tangiers but later engulfed

by the city. Aida became a Pinto by virtue of marriage, her maiden name

being Toledano.

The second book, Aïda Pinto’s memoirs, Mon Passé marocain,

published in 2004, covers almost a century of family history from two

generations later, up to the end of the twentieth century. It describes

more tranquil lives, fortunately hardly affected by the war and the

Holocaust, and seriously disrupted only by the independence period in

Morocco, when the majority of Morocco’s Jews, including most of this

family, over time sought more secure shores. The Pinto family initially

lived in the two villas originally outside Tangiers but later engulfed

by the city. Aida became a Pinto by virtue of marriage, her maiden name

being Toledano.

Despite the Pintos’ humble origins, following the success of the Brazilian enterprise the family came to form a part of the Jewish bourgeoisie -- or perhaps one should say aristocracy -- of Tangiers and Casablanca, both families having overseas business connections. Aida was born in Tangiers in 1923, grew up in a warm but conservative family, moved with her family to Casablanca, attended the Lycée de Jeunes Filles de Casablanca, where there were a few other Jewish young women, many colonial French students, and one Muslim student who hid the fact that she wore a djellaba on the way to and from school. Aïda benefitted from piano lessons, all the accoutrements of a Western education, but still, being Jewish, she felt “A cheval sur deux civilisations” [straddling two civilizations]. She describes the Moroccan Jews as being “une Nation sans Patrie” [a Nation without a Homeland] – a phrase taken from Angel Pulido -- despite having lived in Morocco for centuries. Speaking Haketía and Spanish at home, French in school, and a form of Arabic always mixed with French words (p. 79), like other Moroccan Jews she felt she had no native language.

Aida was a teenager and young adult during the terrible years of the Second World War. Fortunately the lives of her family, though ruled by the Vichy government, remained tranquil and undisturbed. Almost contritely, she describes visits to the beach with friends and family during the thirties and forties. They did not learn about the Holocaust until 1945, but following the terrible revelations, launched themselves into Zionism and Hebrew lessons. From 1948 onwards, life for Jews in Morocco became more insecure and the family lost its carefree character. Nevertheless, Aida led the life of a sociable young woman, working for a charity that gave clothing to poor Jews (Malbish Arouim), and belonging to a carefree circle of young Jewish people which included two Pinto brothers. From 1947 on they witnessed Morocco’s independence process. Having lost her father suddenly in 1945, she lived alone with her mother, learned to drive an enormous Lincoln, travelled often between Tangiers and Casablanca. With her mother she toured Spain and France, took flights from Casablanca, and stayed in hotels in Spain and France, where they often met friends from Morocco and where her mother sometimes regained her joie de vivre.

Eventually Aida married her second cousin Jacques Pinto, giving birth to three children. They lived in the Casablanca villa in which she had partially grown up and where her mother still lived. Family harmony was in contrast with the new sense of insecurity experienced by all Moroccan Jews, French-educated, deficient in Arabic, and emotionally ill adapted to identify with the new nation of Morocco. Photos of family groups and groups of friends attest to years of happiness, which came to an end suddenly with the loss of the family fortune, accidents experienced by a brother and her mother, the death of the same brother due to an allergic reaction two years later, the mother’s passing a little later, all in the early sixties. In 1967, at the time of the Six-Day War, the family decision was taken: they would all move to France. Aida mentions, though, that they have now become déracinés [uprooted] everywhere: able to pick up and move easily but, on the other hand, not connected to anywhere in particular, “Notre vraie place n’est nulle part” (p. 274) [Our real place is nowhere].

The book ends with a chapter of nostalgic reminiscence: of a land of warmth where they were happy, where one could not go out without meeting acquaintances at every corner, a land they felt part of. She reflects that just as Morocco has changed, she too has changed. A large annex reproduces family letters of love and nostalgia from over the decades, most of them in Spanish.

She returns many years later to visit their villa, which has become a municipal museum. On her son’s door she finds his name that he had once carved, all that remains in Morocco of “notre passé marocain.”

* Judith Roumani is editor of Sephardic Horizons.