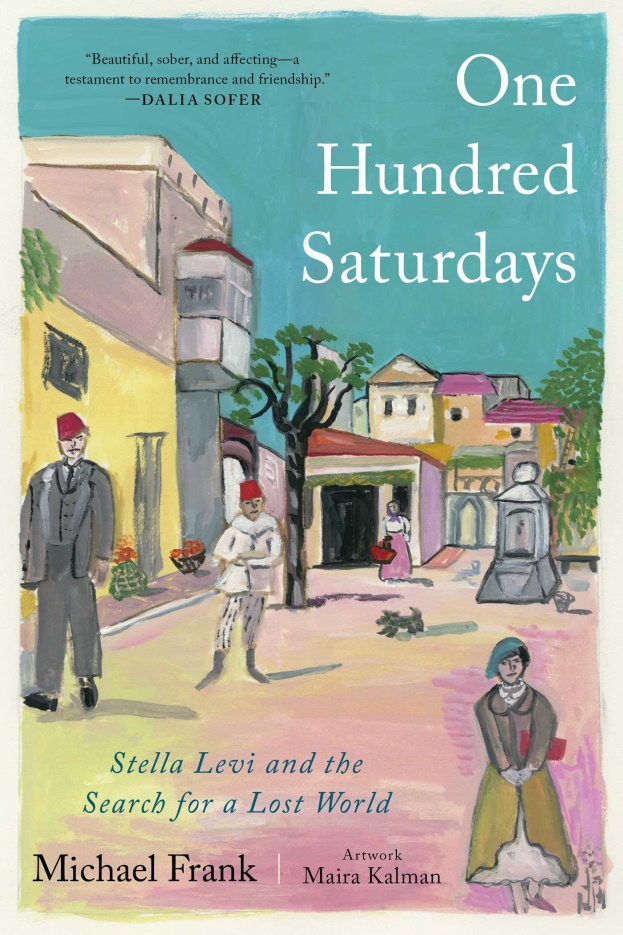

Michael Frank

Artwork by Maira Kalman

ONE HUNDRED SATURDAYS

STELLA LEVI AND THE SEARCH FOR A LOST WORLD

New York: Avid Reader Press, 2022. ISBN: 978-1-9821-7622-6 (978-1-9821-6724-0 [e-book])

Reviewed by Rosemary Lévy Zumwalt1

I pose a question about this account of One Hundred Saturdays. Is this book written in the genre of the interview? the life story? the history of a place and time? or the memoir? In truth, it is all of these and it is more. It is an intensely personal life story, situated in a place and time that was shattered by the Nazi deportation of the Jews of Rhodes in 1944; it is an emotional tapestry of what was lost when Stella, with her budding brilliance in 1938, in accord with the racial laws, was not allowed to go to school (see pp. 78–80). It is a history embroidered with the personal life of Stella. In a YouTube presentation on One Hundred Saturdays held at the Casa Italiana in New York City on September 20, 2022, Michael Frank and Stella Levi addressed a receptive and adoring audience. Frank said, “Stella has given me—and I think at this point, not just me—the gift of her story.” And Stella said, “I am still the little girl and young woman from Rhodes you will find in this book.”2

I should add that for me there is an intensely personal connection to Stella Levi and to her story of the enchanted isle of her birth. My husband of blessed memory, Isaac Jack Lévy, was born on the Isle of Rhodes in 1928 and left with his family in 1939 for the international city of Tangier, Morocco. The two of us knew Stella and knew her sister Sara, the latter whom we visited in her home in Berkeley and in Capitola, California. Isaac, who published on Sephardic topics, frequently pertaining to Rhodes, would call Stella to ask her questions. He regarded Stella Levi as one of the repositories for information about the Sephardic life of Rhodes. Stella Levi is indeed, a treasure for us all and now we have the arc of her life in this book.

In much of One Hundred Saturdays, it is as if my husband of blessed memory and Stella were having a conversation. On page 3, Stella says,

“When I arrived in Auschwitz . . ., they didn’t know what to do with us. Jews who don’t speak Yiddish? What kind of Jews are those? Judeo-Spanish speaking Sephardic Italian Jews from the island of Rhodes, I tried to explain, with no success. They asked us if we spoke German. No. Polish? No. French? ‘Yes,’ I said, ‘French I speak.’”

My husband would always talk about the Sephardim who were deported to the camps and who did not speak Yiddish and therefore were not accepted by the Ashkenazim as Jews. He wrote about this and about other cultural differences that set the Sephardim apart from the Ashkenazim in The Sephardim in the Holocaust, A Forgotten People.3 In a recollection that preceded the tragedy of the deportation of the Jews of Rhodes by about four decades, Stella tells about her paternal grandmother, Mazaltov Levi, who overheard tourists from Spain—in the early part of the twentieth century when ships with tourists began visiting Rhodes—speaking Spanish as they walked through the Juderia (the Jewish section of the old city of Rhodes): “But how wonderful,” she remarked. “They’re all Jews!” (p. 21).

Michael Frank opens the book with a description of the sea, embedded in the soul of all Rhodeslis (inhabitants of Rhodes). The next paragraph of the opening passage focuses on the day of deportation when Jewish life in Rhodes ended. This is also embedded in the soul of all Rhodeslis, whether or not they were among the one thousand six hundred and fifty who were deported in what was known as the longest journey to Auschwitz—a trip of three and one half weeks (pp. 1, 134). Frank gives us a portrait of Stella Levi that is true to the person—her complexity, her intelligence, and her stubbornness or prickliness. We are fortunate that Stella’s personality was so strong, for this insured that she would bring forward what she lived and what she lost. Frank writes in a forthright way in telling us how he conducted the interviews, and, in the process, he reveals Stella’s personality. On page 40, I note in the margin that this is “straight Stella,” when she fires back to his question about boyfriends, “I’m not ready to tell you about that.” In similar fashion, on page 46, Frank asks if her boyfriends were Italian, to which she replies, “That part comes later, Michael—forse”—with the latter word in Italian conveying that there is a possibility that this information will be forthcoming. Stella will choose her time for sharing details of her life. Michael Frank might be the author, but Stella is the director of how this life story will be told.

In what is known among folklorists as meta-narration or the aside, Stella reflects on the passage of time and how this layers new meaning onto old memories;: she brings knowledge from the present to the memories of the past. She recalled a Rhodesli, a wealthy businessman named Rossi, who was a guest at lunch. Always punctilious with his gracious manners, in this instance, learning of the arrival of the Germans on the island, he immediately rose up from the lunch table, went down to the harbor, and hired a boat to take him to Turkey. She reflects on the telling of the story:

“Obviously now when I tell you that story—when I hear myself tell you that story—I hear it differently, but at the time we failed to see the consequences of the Germans taking over as clearly as he did” (p. 102).

Frank shows creativity and wisdom in the transparency with which he reveals the process of the interview; in so doing, he renders it all very immediate and real to the reader. On their second Saturday, Frank relates that after settling into their places, they “sit in awkward silence.” Then Stella queries, “Aren’t you supposed to ask me a question to get me going, like where I was born, or my first memory, or something like that?” She looks at him with eyes that are at once suspicious and provoking (p. 9).

I should have known that Stella Levi was related to Rebecca Amato Levy, who was a friend of Isaac’s and mine. Rebecca was Stella’s cousin (p. 23)—just as I should have known that Stella was a cousin of our friend Aron Hasson (p. 180). As Stella says, everyone is related to everyone else in Rhodes. All of the Rhodesli Jews are “connected—interconnected”; Stella adds, “except when they chose not to be” (62, emphasis in original). “In the Juderia,” Stella says, “everyone knew everyone’s business. More than that: everyone was in everyone’s business” (p. 62). How did news arrive so promptly in the Juderia, Frank asks,

“[W]as it printed in the paper, or came by word of mouth, or . . .,” to which Stella immediately retorts, “The streets themselves spoke. . . . No sooner had something happened, or been disclosed, then everyone knew” (pp. 106–7).

With her characteristic honesty, Stella admitted that it was “potentially claustrophobic” (p. 63). From the discussion of the interconnectedness, Frank posed the rhetorical question, “Related to 10 percent of the people you live among? Is such a thing possible?” Stella replied, “Not only is it possible. I’m still meeting people today that I didn’t know I was related to” (p. 61).

I have witnessed this interconnectedness of Rhodeslis myself. In the reception area of a hotel in Salonika, Greece, in 1990, my husband was waiting for his turn to talk on the hotel phone. I could tell that he was leaning forward to listen to the man using the phone who was speaking in Judeo-Spanish. As soon as the man hung up, I said to myself, “I’ll give them five minutes to find out how they’re related.” It took less time than that. Isaac turned to me and said, “Rosemary, we’re cousins!” To which I said to myself, “Of course you are!”

And I have new-found confidence in the number of relatives my mother-in-law said she had lost in the Holocaust—one hundred and fifty. How is it possible, I always thought to myself, to have lost one hundred and fifty relatives from such a small island? But Frank calculates that ten percent of the entire population of the Juderia, following the number of inhabitants in 1944, would have been one hundred and sixty to one hundred and seventy people (p. 61). So certainly, my mother-in-law’s estimate of relatives she had lost was confirmed by Michael Frank and Stella Levi.

Once the embrace of the narrow, winding cobblestone streets of the Juderia had been loosened, and after the brutal decimation of the Holocaust, a Rhodesli was ecstatic to find and claim relatives. It was a way of convincing oneself that the life of the Rhodesli continued, even though it had been destroyed in Jewish Rhodes. While she was still on the island, the connection with a beloved place had been torn asunder. Walking with her sister Renée to retrieve some items from their home in the Juderia, which they had abandoned because of the incessant bombardment by the British and had taken temporary shelter in the countryside, Stella recalls,

“I knew that the life that had been lived there, with such intensity and for so many years—centuries—was finished. . . . Even if on this actual day I couldn’t put this into words, it is what I knew, what I sensed, in my heart, in my flesh” (p. 119).

In their initial conversations, Stella refused to talk to Michael Frank about her time in the camps (p. 8). But toward the end of their Saturday conversations, she had told him about the whole arc of her life. Frank asks her why she had relented and had told him about the camps: “She thinks for a long time before answering. ‘Because you were patient with me, and because you wanted to know the whole of me’” (p. 162). Stella Levi and Michael Frank take the readers of One Hundred Saturdays on a saga from the embrace of Rhodes to the treachery of the camps, to Italy, New York, Los Angeles, and back to New York, the latter place where Stella felt most at home because there are “so many exiles, so many wanderers like herself” (p. 48).

With pathos, Stella tells of the moment the Americans liberated the camp she was in, the Munich-Allach labor camp. The soldiers were on their way to Dachau; they didn’t even know of the existence of Allach: “The American soldiers threw chewing gum and chocolates over the fence. Just like in the movies.” Stella continues:

“Once we realized we were free, we fell to our knees and started weeping. For all we had been, for all we had lost. We could feel things, we allowed ourselves to experience the pain. We came back to ourselves, we became human once more—we didn’t have to protect ourselves from life” (p. 160, emphasis in original).

Stella Levi lost Rhodes in the ashes of Auschwitz. But she and Michael Frank have given it to us in words and have traced her path from the pain of loss to the connections through friendships. She never was successful in her Search for a Lost World. But she has lived a long, dignified life, and a brilliant life in the world as she found it and shaped it.

1 Rosemary Lévy Zumwalt is co-author with her husband Isaac Jack Lévy of Ritual Medical Lore of Sephardic Women: Sweetening the Spirits and Healing the Sick (University of Illinois Press, 2002). Her most recent publication is Franz Boas: Shaping Anthropology and Fostering Social Justice (University of Nebraska Press, 2022). She is Dean of the College Émerita at Agnes Scott College.

2 Book Presentation by Michael Frank, “One Hundred Saturdays, Stella Levi and the Search for a Lost World,” at the Casa Italiana in collaboration with the Primo Levi Center, September 20, 2022, accessed October 6, 2022.

3 Isaac Jack Lévy with Rosemary Lévy Zumwalt, The Sephardim in the Holocaust, A Forgotten People, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2020.

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800