Michèle Sarde

RETURNING FROM SILENCE1

Translated from the French by Rupert Swyer

Chicago: Swan Isle Press, 2022. ISBN: 9781736189306

Reviewed by Jelena Filipović2

Returning from Silence by Michèle Sarde is a multilayered and polyphonic novel, at the same time a memoir, an autobiography, a biography, and a history book. The author, herself, and her mother, Janja or Jenny, are the principal narrators. The book is written in four hands, a narrative technique that Michèle Sarde uses intentionally in order to give her mother her voice back, the voice silenced by fears and horrors of her ancestors and her own. The text is linear, comprised of facts and details of a family life, skillfully supported by historical facts, names, dates, and toponyms which provide the reader with a perspective of a “grand historical” narrative. Yet, at the same time, it is highly interpretative; Michèle Sarde tries to evoke memories of the events of her early childhood, she tries to imagine feelings of the other protagonists (often providing them with space to use their own voices), she offers her personal visualizations of settings and places. She makes masterly decisions about the historical facts to be included: the general ones, such as the onset of World War II or the Normandy landing, and the particular ones, e.g., the details of the last days of the German occupation of the small village in the Alps where she and her parents spent the last war year.

The storyline covers a period of over forty years, 1917 to mid-1950s, but the voices of its protagonists travel through the barriers of time and can be felt and heard loud and clear by readers of all generations. The history of an extended Sephardic Jewish family starts with their exile from the post-Ottoman Salonica at the beginning of the twentieth century, 1917. Michèle Sarde makes sure to contextualize her narrative. The faith of the Sephardic Jews who had lived in the Balkans for over three centuries was deeply disturbed by the modernist political movements and the creation of nation-states which resulted in marginalization and collective movement of Sephardic communities from some of the newly founded countries, Greece being one of them. The fact that forced migrations have been underlying the Sephardic faith since 1492 has not made them any easier. When describing the abandonment of their burnt houses in 1917, the Jewish cemetery, the life in Salonica, and the family’s movement to France, Michèle Sarde applies an extremely powerful metaphor, often present in Sephardic ballads, of the key to the house left in the Spanish lands to describe the sense of homelessness that has been at the core of the Sephardic existence from 1492. In the novel it is quoted according to the performance of Flory Jagoda, a Bosnian-Jewish-American composer and singer:

Onde esta la yave ke estava en

kashon? Mis nonus la trusheron kon grande dolor. De su Kaza de Espanya, de Espanya.”

Where, but where is the key that was in the drawer? My forefathers brought it with

such suffering from their house in Spain, in Spain.”

Consequently, France is just another geographical and political destination, a modern European state, where they arrive with hopes for an opportunity to live in dignity and free of persecution. At the same time, the family is very much aware of dangers that loom everywhere; the author’s parents change their names to Jenny and Jacques to make sure their Jewish identities are less transparent in their new homeland. The hope for a safer life is, however, short-lived. World War II breaks out; the horrors are back and much worse than ever before in the long history of the Jewish diaspora.

The largest part of the book is dedicated to the wartime years: to the fear, the suffering, the cruelty, and instances of occasional kindness of strangers, acquaintances, and family members alike. The final chapters are extremely heart-wrenching. In them, Michèle Sarde shifts the perspective and uses only her own voice to “return from the silence”: the political silence of the first few post-World War II years in which France refused to acknowledge the Holocaust as a unique historical tragedy never experienced before; the silence of the survivors who had to forget in order to keep on living; and her mother’s silence, the silence of a woman determined to protect the future of her child by total assimilation. This led to Michou’s (Michèle’s) temporary conversion to Catholicism, through which the silence about the Holocaust and the tremendous losses in her family and among her people could be maintained. Michèle Sarde cites her contemporary, Annie Ernaux, to account for the “world of (their) childhood,” when Christianity (…) “was the official framework of life and governed time,” in a country in which,

“as Annie Ernaux points out, they could speak only of what they had seen and known (…) There was no talk of sealed wagons filled with children headed for the slaughterhouse, nor of the large-scale round-ups, (…) nor of the walking dead (…) at holding camps for Jews awaiting shipments eastward.” (Sarde, pp. 316, 318).

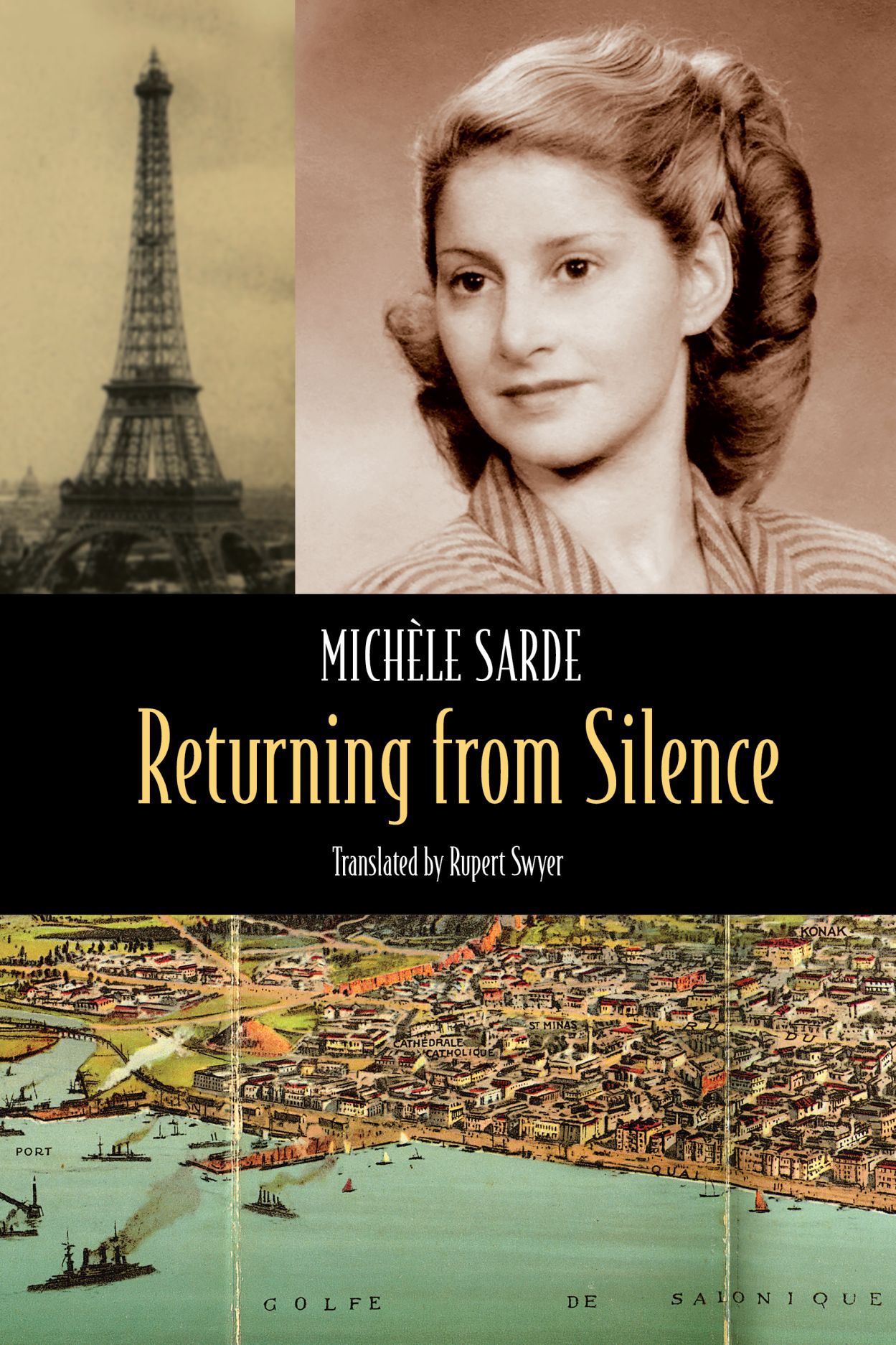

If we look at the novel from critical sociolinguistic and historical points of view, Returning from Silence is a true historical, performative narrative,3 in which the author avoids “imposing her narrative order upon the disorder and multiplicity of histories, and by that token ignoring or erasing other narratives and silencing other voices”.4 Quite to the contrary, Michèle Sarde constructs a multimodal text using not only words, but also visual materials including family photos, family trees, postcards, and so forth to open space to her readers for a more profound understanding of the complex storyline. Moreover, and more importantly, in Returning from Silence Michèle Sarde shares with her audience a feminine, personalized, and very private account of the most tragic period in Jewish history. By combining her mother’s memoirs with her own experiences and with general historical knowledge, Sarde provides us with an exceptional opportunity to not only accept her interpretations, but also create our own reconstructions of complex historical processes and their impact on lives of concrete individuals.3

1 This book in the original French "Revenir du Silence" won the Grand Prix WIZO in 2017.

2 Jelena Filipović, Ph.D., is a professor of Spanish and Sociolinguistics at the Department of Iberian Studies of the Faculty of Philology, University of Belgrade.

3 Munslow, A. 2012. A history of history. London: Routledge.

4 Weinstein, B. 2005. History without a cause? Grand narratives, world history and the postcolonial dilemma. International Review of Social History, pp. 71-93.