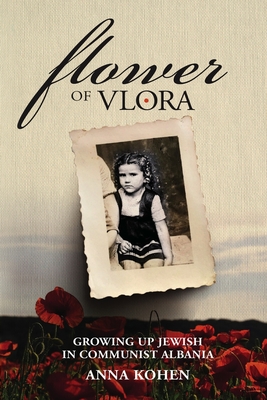

Anna Kohen

FLOWER OF VLORA

GROWING UP JEWISH IN COMMUNIST ALBANIA

The Netherlands: Amsterdam Publishers, 2022. ISBN: 9789493276246

Reviewed by Annette B. Fromm1

Dr. Anna Kohen is a singular Jewish woman who grew up in Albania during its darkest years. In this volume, she documents the history of the Kohen family history in Vlora, now the Albanian Riviera, from the late 1930s to the present. Actually, her text briefly introduces tidbits of Albanian Jewish history including how her family, originally from Ioannina, Greece, found themselves working and living there. She amply illustrates how they, and other Albanian Jews, were able clandestinely to keep alive their traditional practices while living in what might have been the most stringent of communist regimes. As well as hiding evidence of their faith, they spoke little of their experiences during World War II.

Saimir A. Lolja briefly introduces readers to the history of Jews in Albania. His introduction emphasizes the story of their fate during World War II, a story only recently coming to light. He writes in some depth about the remarkable and unique characteristic of Albanian identity, besa, a pledge that ventures beyond simple hospitality or the so-called Golden Rule.2 The history of the saving of Jews in neighboring Kosovo during the same time is also detailed.

Kohen starts her meandering narrative with memories of her childhood in Communist Vlora. Her grandparents were relative latecomers to Albania, having emigrated from Ioannina in 1938. Her family was not able to become Albanian citizens. This situation was a slight handicap when Kohen entered medical school. It also helped the family escape from the country before the fall of the communist regime.

In Vlora, they joined other Jewish families who had ventured northward some decades earlier. Her grandfather was seeking a better economic situation in taking the family to Albania. With a brother, he established a textile business specializing in dying fabrics and printing scarfs. Her father frequently took merchandise to surrounding villages in the region, trading with Muslim villagers. Eventually readers learn that the entire family took part in the textile business, even the children pitched in before playing in the summer. The Kohen family was anchored by a strong, business-minded paternal grandmother, well-known and respected in the marketplace for her bargaining skills. The author credits her own business acumen in later life to lessons learned from her grandmother and her parents as a youth.

She also writes about her own experiences during the many years of the communist regime. One of the difficulties during the time under the leadership of Enver Hoxha that Kohen relates in detail was her strategy to get around the standing in endless ration lines. Other necessities and conveniences lacking in the lives of Albanians during that period ranged from an inadequate healthcare system; modern household items such as refrigerators, vacuum cleaners, and televisions; automobiles; limitations of travel within the country; and access to books from the West. On the other hand, primary and secondary education was available for everyone. Despite the deprivations and stress associated with the repressive political regime in which she grew up, she recalls her youth with Jewish, Christian, and Muslim friends. All the teens socialized together at the beach and elsewhere. Interwoven in her narrative of growing up in Albania are a few relationships with young men and several instances of matchmaking. Each step of the way, Anna left behind a boyfriend. She regales readers with her various romances until finally she met her husband in the United States.

Among the memories that Kohen briefly shares are the Passover celebrations led by her grandfather and phrases of the so-called Romanioti language spoken in her family. She writes that holiday celebrations in her home included special recipes that the family brought from Ioannina. They often included walks in the city center or long bus rides to the seaside.

She also describes the Muslim villages in the area around Vlora. These were villages in which Jewish families were hidden during the German occupation, from 1943 to 1944. Her stories of the war years and earlier, however, were those she heard as a child some years afterwards.

At eighteen, Kohen enrolled first in medical school, then dental school in Tirana. While living in the university dormitory, she established connections with Jewish families in the capital. Kohen stood out from her fellow students because her family remained citizens of Greece; she did not receive free tuition as did the Albanian students nor could she eat for free in the cafeteria. For the same reason, her older brother could not enter university. The siblings, however, were eventually able to continue their studies.

By the mid-1960s, Kohen’s father put into action a plan to get his family out of Albania. With his mother, he was able to travel to Greece, a rare occurrence during the communist years. They also went to Israel to visit family they had not seen since before World War II. They convinced officials that he would return with some inheritance waiting for him there and he would then, become a citizen. Upon their return, with the money, the Albanian secret police came to hold him to his promise to become an Albanian citizen. He feigned an illness that required specialized surgery not available in Albania. Kohen skillfully weaves together the long and convoluted efforts through which the family was able to leave in July 1966 from a country closed off to the world. Among her experiences during their departure from Albania was her first encounter with a banana on the flight from Tirana to Rome. It was a fruit the family had never met before. They watched their fellow passengers, all from China, and followed suit.3

Kohen had finished two years medical/dental school in Tirana. After the family departed, she was able to complete her studies in Athens. Most of her family, however, left Greece to settle in New York. Upon the completion of her education, she joined her family there and eventually was able to practice the skill she had learned. Dentistry was the career that she successfully continued her entire professional life.

Helping has always been at the forefront of Kohen’s life. Her descriptions of the kindness her parents showed their customers in Vlora, especially the frequent bartering for goods and services during what she calls the “dark years” of communism is probably what established a life-long sense of philanthropy. She shares many examples of how she reached out to others. Once she established her own dental practice, she started offering services to the members of the Albanian mission to the UN. As a result, in 1989, Kohen and her family were invited to visit her homeland, still closed to most outsiders. After that visit, Kohen’s efforts turned to arranging for the Jews remaining in Albania to leave. Many of them went to Israel; members of Kohen’s family went to America instead.

Kohen writes of the limbo that was a crucial part of her life: her family never took Albanian citizenship. Yet, she has always “considered myself an Albanian Jew” (xii). Furthermore, through an active life of nonprofit and charity work with Albanians and Albanian immigrants in the United States, she has shown herself to be “Albanian.” Her philanthropic commitments are divided between Albanian American organizations and Jewish institutions such as the Albanian American Women’s Organization (Motrat Qiriazi) and the International Holocaust Remembrance Day in Sarasota, Florida. The Albanian government and the Jewish community have recognized her for the charitable activities that have been part of her professional life.

This book introduces readers to the complex life of a remarkable Albanian Jewish woman. It also provides glimpses into the little-known history and life of Jews living in Albania, especially during the indescribably harsh years of extreme communism. One message I took away from her narrative is that Anna Kohen, following the example of a strong Greek-Jewish grandmother, has successfully worked against restrictions inherent in patriarchal societies. She prides herself on her heritage of a Greek-Jew from Albania as well as the strides she has made as a feminist.

1 Annette B. Fromm is a museum specialist, folklorist, and lecturer in Romaniote and Sephardic studies and associate editor of Sephardic Horizons.

2 A recent film titled Besa, was widely viewed during the two years of Covid. See review in Sephardic Horizons, Vol.3- Issue 3. Another film, The Albanian Code, traces one family who found the Albanians who saved them.

3 While on a recent trip to Albania, a tour guide related a story of the response to the introduction of bananas in the country. Like the Kohens, others did not know what it was nor what to do with it. His comments made me recall oral history interviews I collected in the late 1970s from European immigrants to America. They did not understand that the outer peel was not an edible part of the fruit.

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800