The Mellah of Fez

Abode of Moroccan Jews and Center of Their Activities

Mohamed Chtatou1

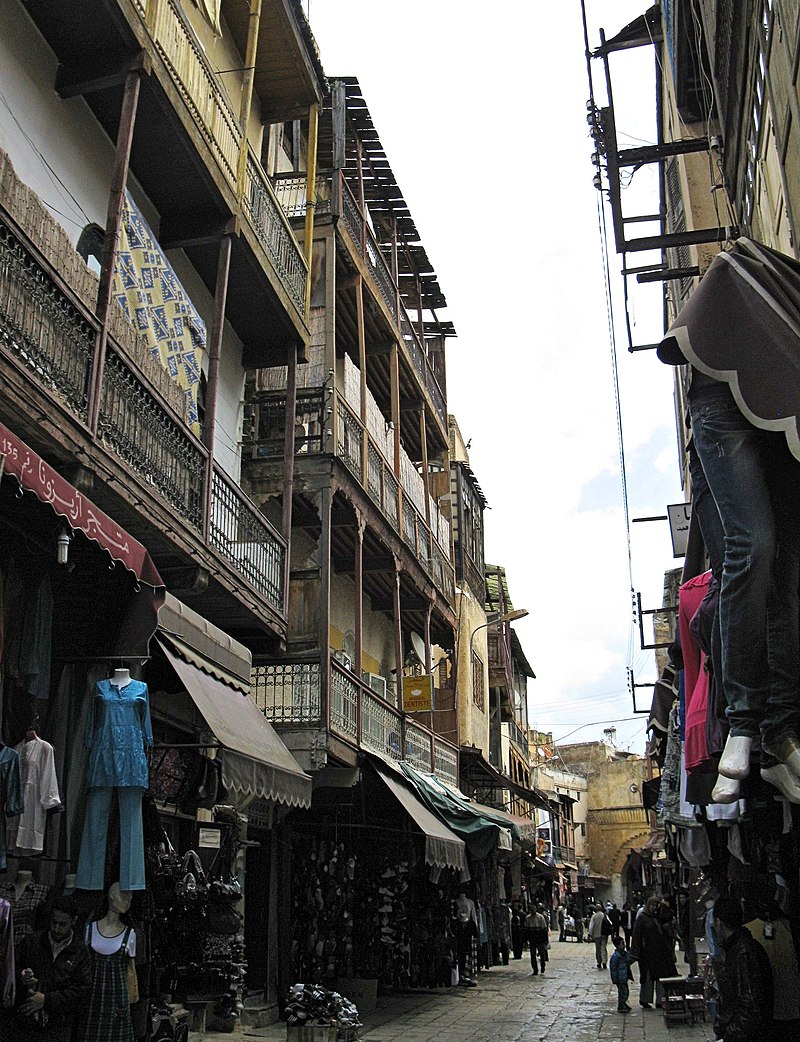

Mellah of Fez (Photo by Robert Prazeres)

Jews have lived in Morocco for over two thousand years.2 In the countryside, they lived in the midst of Amazigh people with whom they shared many particularities such as tribal identity and solidarity, and matriarchal features.3 In the cities, they first lived in the outskirts of the urban organization; later because of pogroms, they were placed in walled structures near royal palace, or the residence of the governor, to protect them from periodic revolts, but there were, also, separate rural mellah villages inhabited by Berber Jews.4

First, there was the mellah of Fez

In 1276, the Marinid Sultan Abu Yusuf Yacqûb (1212-1286) founded Fâs aj-Jdid, a new fortified administrative city to house his troops and the royal palace. The city included a southern district known as Hims, which was initially inhabited by Muslim garrisons, particularly the sultan's mercenary contingents of Syrian archers, who were later disbanded.5 The same district, however, was also known as the mellah (salt area) due either to a source of salt water in the area or to the presence of an ancient salt warehouse. It was this name that was later retained as the name of the Jewish quarter.6

The mellah of Fez is the oldest Jewish quarter in Morocco. It was established in 1438.7 Previously, from 808 to 1438, Jews and Muslims lived together in the medina. There the Jews had properties, synagogues,8 and a cemetery. The Jews were settled in various districts of the medina. The last one to date is Ezensfor where the Jewish cemetery was within the walls, next to Bab l-Guisa.9 In the Blida quarter there was a street called Derb Essefer, or the street where there was the Sefer, the Book of Law among the Jews. Derb Zniara is named after a Jew, Zniara, who was the vizier of a Sultan Bel Messâl at that time. Trade was developed, and local industry was diversified: goldsmithing, jewelry, silver, gold wire, trimmings, and clothing.

Since 1438, according to legend, because of a dispute caused by the presence of a few bottles of wine, there were massacres of Jews in the medina. The sultan at the time ordered their transfer to a new district close to the palace to provide them with better protection. Thus, the first mellah came into existence in Fez in 1438; other cities built similar such walled quarters for the Jews much later. On May 14, 1465, almost all the Jews of Fez were killed,10 in the bloodiest pogrom in Moroccan history, by rebels who killed Sultan Abu Muhammad Abd al-Haqq (1420-1465), bringing down the reigning dynasty in defiance of the Marinid dynasty. The immediate cause of the anti-Semitic violence was the appointment of the Jewish vizier Harun (Aaron) ibn Batash by the sultan.11

Another legend places the residence of the philosopher rabbi Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides and referred to by the acronym Rambam (Hebrew: רמב״ם),12 in the district of Fondoq Lihûdi, in Bab l-Guisa, where the Transatlantic Hotel was built in 1923. Until the Protectorate, it was traditional that Jewish women, especially those who had no children, made a pilgrimage to this place in the Talca, an uphill section of the medina where they implored the intercession of the Rambam to have children. A Muslim moqaddem (civilian official) was in charge of this place.13

The unification of Morocco and Muslim Spain by the Almoravid dynasty (1050-1147) promoted the exile of scholars to Fez, the new center of civilization.14 It also contributed to the material prosperity of the city15 which became the cultural, economic, and military center of this vast empire in which Jewish traders played a leading role. The great Arab geographer of the time, al-Bakri,16 wrote:

"The Jews are more numerous in Fez than in any other city of the Maghreb and it is from there that they radiate for their business in all parts of the world."

Star of David on a door of a cemetery in the Fez mellah. (Photo by Werner 100359)

The exact reasons for and date of the establishment of a separate Jewish quarter in Fez are not firmly agreed upon by all scholars. Historical accounts confirm that in the mid-fourteenth century the Jews of Fez were still living in Fâs al-Bali (the old city), but that by the end of the sixteenth century they were well established in the mellah of Fâs aj-Jdid.17 Some authors argue that the transfer probably occurred in stages throughout the Marinid period, late thirteenth to fifteenth centuries, particularly after episodes of violence or repression against Jews in the old city.18 The urban fabric of the mellah seems to have developed gradually. It is possible that a small Jewish population settled there just after the founding of Fâs aj-Jdid and that other Jews fleeing the old city joined them later.

Some scholars, citing historical Jewish chronicles, attribute the date of the move more specifically to the "rediscovery" of the body of Idris II in his zawiya in the center of the old city in 1437.19 It became an important place of pilgrimage in the fifteenth century and is still considered the holiest place of Fez. The surrounding area, located in the middle of the city's main commercial districts where Jewish merchants were very active, was transformed into a horm (sanctuary) where non-Muslims were not allowed to enter, resulting in the expulsion of Jewish inhabitants and their businesses.20 Others date the movement generally to the middle of the fifteenth century. In all cases, the transfer, whether gradual or sudden, occurred with some violence and difficulty.21 Many Jewish households chose to convert, at least officially, rather than leave their homes and businesses in the heart of the old city, resulting in a growing group called al-Baldiyyin, Muslim families of Jewish origin, often retaining Jewish surnames.22

The Muslim community, in general, did not deny the Jewish and Christian communities, Ahl al-Kitāb the "people of the book." They were recognized as "imperfect" religions, certainly, but respectable in their monotheistic anteriority, which is rooted in a common Semitic cultural heritage conferring on them legal status. As a result, such status provided them with dhimma protection, and obliged them to pay the jizya, a head tax for protection.23

Origin of the word mellah

The word mellah in Arabic: ملاح, means literally مِلَحْ,"salt" or "salt area." It also refers to a place where products are preserved with salt. In every Moroccan city, however, it refers to the Jewish quarter. This may be because a chore imposed on the Jews of Morocco was to salt the heads of executed criminals to preserve them before they were displayed at the city gates, to set an example to any future rebellion against the makhzen (traditional central power).24

This etymology seems to be considered popular. The origin is more likely the Hebrew מִילָה ("mila," circumcision, the covenant made with Abraham) which passed into classical Arabic in the feminine form "مِلَّة" ("millah," Abrahamic religion), and then into Moroccan Arabic with shortening of vowels ("mella," moral principles, religion). The terminal H of this word is a Ta marbota which is never pronounced in modern Moroccan Arabic. The transition to the devoiced H (ح), making the word sound like the family of ملحة (“melHa," salt in Moroccan Arabic) remains poorly documented. Indeed, historical writings, French or Spanish, cite the word in Latin characters, with confusion of "ة" (feminine final where H is unpronounced), "ه" (H voiced), and "ح" (H devoiced). Other writings in Hebrew are not widely available.

Mellah can also be traced to a biblical expression that means "lasting." It is, in fact, used in the text, "bereth melah" to designate a lasting covenant (Bereth melah ôlam, the covenant of salt forever, Bamidbar 18/19).25 If this explanation were true, the Jews themselves would have given their neighborhood the name mellah to wish themselves a lasting settlement. Another explanation is traced to the word mellah which could come from the Hebrew "malahim" which means “sailors’’ (pl.) or mallah (singular).

The name, mellah, therefore, originally had no negative connotation but was rather just a local toponym. Nevertheless, over the generations, a number of legends and popular etymologies have come to explain the origin of the word, such as "a salty and cursed ground" or a place where Jews were forced to "salt" the heads of beheaded rebels.26

Nature of the mellah

The most important characteristics that differentiate the Jewish quarter from the Muslim communities can still be appreciated. One of the most important details concerns the construction of the buildings. Jewish homes have exterior balconies with wrought iron latticework to, apparently, protect women from inquisitive external eyes. The windows in Muslim houses face an interior courtyard.

For the Tharaud brothers, who visited Marrakesh at the beginning of the twentieth century, the mellah was:27

Un des lieux les plus affreux du monde

(one of the most dreadful places in the world).

Today, when you walk through the old quarter of the mellah of Fez, which is no longer in good condition, you will notice that it differs from the other part of the old medina by the very particular architecture. On the main street of the mellah, jewelers' shops occupy the ground floor of the buildings. Above are beautiful facades and wooden balconies.

The mellahs, walled on all four sides and generally closed, housed the Jewish population of Moroccan cities.28 As a result, these spaces fostered Jewish communal life. Mellahs were generally organized into neighborhoods with synagogues, a Jewish cemetery, and kosher markets located among other public spaces. Even the synagogue itself facilitated a wide variety of Jewish communal needs, including education, ritual baths, and spaces for children to play.29 While at first in the fifteenth century, these neighborhoods, with spacious homes and protection due to the proximity of the royal palace, offered considerable comfort to Jewish families, these luxuries soon came to an end.

However, over time, the narrow streets of the neighborhoods became crowded and overrun with people, and they became synonymous with ghettos. Jews were confined to the inner walls of dilapidated mellahs, and the areas became associated with cursed and "salty" lands, just as Jews were perceived in Moroccan society.30

Because Jews were key players in artisanship, trade, and commerce, mellahs were often located on major waterways and were generally close enough together to effectively facilitate trade networks.31 Even more, the mellah market became a prominent space not only for the Jewish community, but also for non-Jewish people who came to shop on market days. Because Jews generally held positions as merchants and artisans, the mellah was an attractive trading post for the entire city, not just the Jewish quarter.32 The separation certainly stifled cultural interaction to some extent, but Muslims were allowed to enter the mellah and did so if they needed goods and services that fit into the Jewish niche.33 The mellah also played the role of the financial center of Moroccan cities; makeshift banks, located in tiny shops, offered loans to ordinary people and conducted financial transactions.

The mellahs of Morocco emerged mainly when Jews migrated to Morocco after being expelled from the Iberian Peninsula in 1492 during the Spanish Inquisition.34 There were two main justifications given for their construction:

First, these Jewish neighborhoods were often in close proximity to the ruling local authorities, offering a form of protection to the Jews. This explanation also relates to the resulting effective authority over the different religious populations; if all the Jews are physically together, it is easier to maintain effective control over them, assess taxes, and count the community; and

The second justification for the cause of the institution of the mellah is the idea that the mellahs were a "collective punishment for specific transgressions." Jews were associated with ethical deviance, physical deformity, and disease, and were therefore separated from the Christian and Muslim populations.35 The organization of the city as a whole provides insight into the situation of Jews in relation to the Muslim majority and the relevance of these justifications to specific mellahs. As Gilson Miller et al. write:36

Sometimes the neighborhood is contained within the larger city and forms a microcosm of it, such as the Jewish quarter in Tetouan; at other times it is removed from the molecular city and attached to the royal enclave, as in Fez. The neighborhood invites speculation about its origins and the relationship between the Jewish minority and the Muslim majority. Was the purpose of the neighborhood to isolate its inhabitants, to safeguard them, or both? In Fez, the proximity of the mellah to the royal palace is often read as a sign of Jewish dependence on the power and protection of the ruling ruler.

While the location of Jewish settlement was generally imposed by Muslim rulers, the mellah existed relatively autonomously, with Jews building and sustaining their own communities within the walls of their neighborhood. Indeed, there was resistance to forced relocation, but eventually, the Jewish mellah became a sanctified space of which Jews were proud.

For Gottreich, the door of the Marrakesh mellah had a special significance for the Jews:37

The one gate that gave way to the medina, which could easily have been repudiated as an emblem of imprisonment, was instead treated as an object of reverence by the inhabitants of the mellah, as we see in this early twentieth-century description: If one stops for a moment in front of this door, one sees a curious thing: all who pass by, children, beggars, peddlers driving their donkeys loaded with goods, old women, bent men, all approach this dusty wall and press their lips against it as fervently as if they were kissing the holy Torah.

Moses Ben 'Attar was one of the Jews who rose to fame from the mellah of Meknes. This merchant became one of the Jewish favorites of Moulay Ismail (1645-1727) and ultimately: tâjer as-sultân (sultan’s merchant), a very prestigious and rewarding position, politically and financially. His financial genius and the gifts he lavished on the ruler's favorites ensured his great credit. Appointed sheikh of the Jews, Sheikh Lihûd, jointly with Abraham Maymorān whose daughter he married after having been his rival, he commanded all his co-religionists. His actions had been the cause of the ruinous setback imposed in 1716 on French trade.38 In 1720 and 1723, he took part in the negotiations for the redemption of the English and French captives and made them pay dearly for his help. The wealth he had amassed aroused the covetousness of the sultan, who demanded from him a tribute of twenty quintals of silver. He fell into disgrace at the end of his life and died in Meknes in September 1724.39

The expulsion of the Jews from the mellah of Fez

In 1790, the Alaouite sultan Sidi Mohammed (1721-1790) died in Rabat. His son Moulay al-Yazid (1750-1792) who had rebelled against his father during his lifetime, was proclaimed sultan in his place.40 He transferred the black slaves who were camped in the vicinity of Meknes to Meknes itself, and the Oudayas (sultan’s military tribe), numbering 3,000, were moved to Fez from their camp in Meknes. The location chosen was the mellah. In the same year, the Jews of Fez were ordered to vacate the mellah, their houses, and their synagogues to settle in the qasbah of Cherarda. It is not necessary to describe in what conditions this hasty transfer took place. They could not take their belongings or their furniture because the deadline was only one day.

As soon as they settled in the qasbah, they erected nwâlas, or huts made of reeds covered with earth, in the manner of the nomads. There was no water and they had to buy it from the peasants who brought it from the distant wâdî (river bed). The dead had to be buried in another remote location called al-Guisa, which was located upstream from the Dhar l-Mehraz neighborhood.

Berbers from the Ait Yammûr and the Oudayas settled in the mellah. To make themselves comfortable, they destroyed the synagogues, the tombs, and the cemetery of the Megorashim, Jewish expellees from Spain, who had lived there for three hundred years. Their dead were dug up. The Jews were allowed to take the bones of their dead only one day a week, on Friday. These bodies, collected in earthenware jars, were transferred and reburied in the al-Guisa. The new residents of the mellah built a mosque and a minaret on the site of the synagogue with the materials from the demolitions.

To make matters worse, and one can also say that something bad is good, a fire broke out in the nwâlas or huts of the qasbah in 1792, on the feast of Sukkot. This was after the evening prayers on the seventeenth month of their stay in the qasbah, on the day before Simha Torah. The qasbah's caid (governor), his men, and all the Jews struggled all night to control the fire. More than two hundred nwâlas with their furniture, a synagogue, a Sefer Torah, books, and provisions accumulated for the year fell prey to the flames.

In their growing misery, the Jews turned to Sultan Moulay al-Yazid’s mother, who wrote a letter to her son in Meknes, imploring him to return the mellah to the Jews. In the meantime in the same year, Sultan Moulay al-Yazid died during a battle near Marrakech and his grandson, Moulay Slimane 1766-1822), a wise and pious man was proclaimed sultan.

Later in 1792, the Jewish notables were received by Sultan Moulay Slimane when he left for Meknes. He welcomed them and asked them to designate three men to travel with him to Meknes, promising to give them satisfaction. The three notables, Joseph Attia, David Lakhrief, and Benyamin Bensimhon, accompanied the sultan to Meknes where they stayed until the second day of Passover. They were brought to the Caid Ayyad, governor of Fez, and the order to evacuate the mellah and to reinstall the Jews in their neighborhoods and homes was issued.41

Having been forced to note that the mellah was the property of the Jews and that the mosque had been built with stolen materials from Jewish cemeteries, the sultan ordered the destruction of the mosque and the minaret. A house was built on the same site which still bears the name of Dâr Ezcamâ (House of Bravery). The Jews stayed in the qasbah twenty-two months.

The communal authorities of the mellah of Fez

The organization of the Jews in their neighborhood took into account many questions that were generally unknown to the Muslim milieu. The Jewish community of Fez was run by three different organizations:

The Rabbinate was in charge of justice between Jews;

The Hebrot were responsible for all the charitable works such as the traditional religious ceremonies related to weddings, deaths, and charity, in general.

The Sheikh Lihûd acted as an intermediary between the pasha (governor of the city) and the Jewish community. Simply stated, he was the official representative of the Jewish community before the authorities and the sultan.

The Rabbinate: Jews enjoyed religious autonomy in Morocco. The Rabbinical Court dealt with civil status and settled disputes between Jews. Among rabbis, there were rabbi-judges (dayanim) and other rabbis whose functions were different. There were several rabbi-judges who had an important influence on the community. Each one separately could make judgments about any dispute between Jews who came before him. When a significant dispute arose and the parties concerned requested the composition of a court, three rabbis were appointed. When the community needed to make important decisions, the assembly had to be composed of all the rabbi-judges and seven notable members of the community.

Each rabbi had his own private synagogue where he taught Talmud during the week. The rabbi-judges supervised the application of the Jewish faith within the community. Other rabbis (sohatim) were responsible for the slaughter of animals for the consumption of kosher meat. Others served as rabbi-officiants in the synagogues. Still, others were appointed as notaries (suffrim). Those who performed circumcisions were the mohelim. Finally, some rabbis were singers and sang liturgical songs in Hebrew on all festive occasions, in the synagogues on Saturdays and holidays and for wedding ceremonies, tifilim (bar mitzva), circumcisions, and so forth. These singers were called paytanim. It was customary to make offerings on the Sabbath (orally, that is, since the exchange of money is forbidden on Saturdays) for the benefit of the officiating rabbis, the rabbi-judge, the paytanim and the beadle of the synagogue at the synagogue where the family prayed. These emoluments alone allowed them to provide for their needs.

The Hebrot: "Hebrath gomle hassadim" was composed of several distinct groups with different functions. They were made up of pious and honest people, with a real influence in the community. Each was responsible for the management of the property allocated to the poor and for charitable works. They were well-equipped and well-organized, and were also solicited in case of necessity to bring immediate help to members of the community in case of disaster, fire, flood, epidemic, or other calamity. Thus, many of the hebrot members went to the aid of the inhabitants of the neighboring city of Sefrou during the floods in 1890.

Among the different hebrot, there were those who were in charge of collecting and distributing the bread prepared in each family for the needy on the eve of Shabbat. From the community leaders, the annual subscriptions for the benefit of the poor were collected for the distribution of subsidies on the eve of each of the three major religious holidays: Pesach, Sukkot, and Shavuot.

Another hebra took care of the funeral services on a voluntary basis. A team of fourteen moqaddams or leaders was in charge of all the work to be done at this time of need. Some assisted the dying person by reciting the customary prayers. The washers or rohussim took care of the mortuary rites, which included the ablutions. The haffarus carried out the digging of the grave and the burial. A team of gravediggers, led by one of the hebra members, prepared the grave on the day of the death, as it is traditional not to dig a grave before the confirmation of a death. Another group called Hebra Sghira, the little hebra, took care of the ablutions and the burial of the little children.

When the deceased was a rabbi or a prominent person, hebra members accompanied the family to the cemetery after the morning prayers and recited psalms and prayers. This continued for thirty days except for Saturday. On Saturday, the members of the hebra would visit the family of the deceased after the morning prayers in the synagogue and again recite the appropriate prayers.

Synagogue Danan in the mellah of Fez. (Photo by Ricardo Tulio Gandelman)]

The hilûla pilgrimage42 of Jewish saints was the responsibility of another hebra. For example, a hilûla is held on the anniversary of the death of Rabbi Simon Bar Yohai in all Moroccan Jewish communities with a ceremony when the Zohar (Splendor), part of his writings, is recited. In Fez, this pilgrimage is celebrated with prayers in the synagogue and singing in Hebrew, including songs composed in his honor. Candles are also lit in his honor and in honor of his disciples. These candles are sold at an auction beforehand.

Another hebra handled the wedding ceremony. Members of the hebra would go to the groom’s house after the Saturday prayers on the week of the wedding. They would make him walk to the bride’s house while songs about the wedding and other events were sung in Hebrew. His parents were part of the procession. It should be remembered that on Saturdays all the stores in the mellah were closed and no foreigners were allowed to enter the Jewish quarter. The celebrations continued with the help of the hebra at the bride’s house on the following Wednesday. After the morning prayers, the members of the hebra would go to the bride’s home in order to bring her to her husband-to-be. Dressed in rich clothes and covered with gold jewels, her face veiled, she would be seated on a chair that a man carried on his head. The whole journey to the bridegroom's house was carried out in an equally picturesque way, with wedding songs sung in a loud voice in Hebrew. Festivities continued there including the wedding ceremony.

Other uses of the mellah

It was customary in the makhzen (central power) for unofficial foreigners coming to settle in Fez to be placed with the Jews in the mellah. In addition, by order of the pasha or governor, exotic animals offered as gifts to the sultan were installed in the vicinity of the mellah. Thus, a menagerie of a few lions was housed in two appropriate buildings located in the street of al-Qaser, in the mellah in 1776. A small apartment called Mesrîyah d-Nesranî was built next to these houses for the European trainer who, assisted by a Jew, Jacob Malka, took care of the lions.

In 1880, Queen Victoria of England offered a large Indian elephant called Stoke, accompanied by his Indian mahout, to the sultan of Morocco, Moulay al-Hassan I (1836-1894). The admiration of the local residents was aroused when the mahout went up on his elephant. A Moroccan chronicler recounts that the pachyderm landed in Tangier, not without difficulty. The landing was done in the harbor and it was very difficult to get him from the ship to a boat. When he was placed in the boat, it almost capsized with its crew.

When the elephant arrived in Fez, the caïd of the time made him and his companion stay at the house of Sheikh Lihûd, chief of the Jewish quarter, who lodged the cumbersome animal in a large fondoq, a vast room located near the Jewish cemetery. The mahout lived in a small house next to the fondoq. This place kept the name of Derb al-Fil, the “street of the elephant,” for a long time

When the elephant died a few years later because of the climate and the lack of freedom, he was given a resounding funeral due to the elephant’s status as a sacred animal for the Indians. He was buried in a plot of land in the Jewish cemetery at the time, in a space limited by the walls that separated the cemetery from the premises adjacent to the Palace. A mound called Râs al-Fîl was built over his grave, where the tombs of the old cemetery remained and where wild herbs grew freely. This place, often frequented by truant children and card players, has been flattened over time and as a result of the construction of the new doors of the Royal Palace (Dâr al-Makhzen).

Jewish cemetery in the mellah of Fez. (Photo By Selina Bubendorfer)]

In Conclusion

For nearly twelve hundred years, the history of the Jews of Fez was intertwined with that of the city and its human, economic, and cultural components. At certain times, it even marked the course of the city, as in the 1465 rebellion and pogrom of Fez. From the eleventh century until the beginning of the twentieth century, the large groups of Jewish origin who converted, willingly or by force, to Islam (the Baldiyyîn) and the expellees from Spain contributed to the social and intellectual movements that nourished the economic and political life of Muslim Fez and forged its reputation as a great and influential metropolis in the history of Morocco.43

Compared to the other Jewish communities in Morocco, the community of Fez44 has, since its formation, held the undisputed role of creative and cultural leadership; more often than not, it has had the largest Jewish population.

Oren Kosansky writes on the Jewish nature of Fez:45

“Moroccans also consider Fez to be a Jewish city. The "Jewishness" of Fez and its population often entails two claims. First, Fez was home to Morocco's original segregated Jewish quarter (est. 1438), which later became known as the mellah. Second, some of the most renowned Muslim families of Fez had Jewish origins. Family names like Ben-Choukroun or Ben-Soussan, shared by both Muslims and Jews, are said to indicate a Jewish source. Ben--read as a Hebrew word meaning "son of," and opposed to the Arabic variant, Ibn--is commonly taken by both Muslims and Jews as proof of Jewish ancestry. To situate this possibility in historical terms, Moroccans sometimes invoke periods of mass conversions of Fasi Jews under the rule of medieval Moroccan dynasties.”

1 Mohamed Chtatou is a senior professor of North Africa and Middle East Culture at the International University of Rabat -IUR-. He is also a specialist in Moroccan Jewish legacy and a political analyst on Islamic politics and Islamism.

2 Zafrani, Haim. Two Thousand Years of Jewish Life in Morocco. Brooklyn, New York: Ktav Publishing Inc., 2005, trans. of Deux mille ans de vie juive au Maroc: histoire et culture, religion et magie. Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose; Casablanca: EDDIF, 1998.

3 Ben-Layashi, Samir & Maddy-Weitzman, Bruce. "Myth, History, and Realpolitik: Morocco and its Jewish Community," in Abramson, Glenda (ed.). Sites of Jewish Memory: Jews in and from Islamic Lands. London: Routledge, 2018.

4 Gottreich, Emily. Jewish Morocco: a history from pre-Islamic to postcolonial times. London: I.B. Tauris, 2021.

5 Bressolette, Henri & Delarozière, Jean. "Fès-Jdid de sa fondation en 1276 au milieu du XXe siècle." Hespéris-Tamuda, 1983, pp. 245–318.

6 Le Tourneau, Roger. Fès avant le protectorat: étude économique et sociale d'une ville de l'occident musulman. Casablanca: Société Marocaine de Librairie et d'Édition, 1949.

7 Gilson Miller, Susan; Petruccioli, Attilio & Bertagnin, Mauro. "Inscrire l'espace minoritaire dans la ville islamique: le quartier juif de Fès (1438-1912)," Journal de la Société des historiens de l'architecture, 60 (3), 2001, pp. 310–327. doi : 10.2307 / 991758. JSTOR 991758.

8 Weill, Julien. Le Judaisme. Paris: Félix Alcan, 1931. ‘’La petite synagogue moyenâgeuse d'un mellah marocain,’’ ‘’ The small medieval synagogue of a Moroccan mellah,’’ p. 88.

9 Tolédano, J. L'esprit du mellah: humour et folklore des juifs du Maroc. Jerusalem: Editions Ramtol, 1986.

10 García-Arenal, Mercedes. “The Revolution of Fās in 869/1465 and the Death of Sultan ’Abd al-Ḥaqq al-Marīnī.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, vol. 41, no. 1, 1978, pp. 43–66, pp. 46–47. JSTOR

11 Ibid., pp. 45–46.

12 Kraemer, Joel L. Maimonides: The Life and World of One of Civilization's Greatest Minds. New York: Doubleday, 2008.

13 Gerber, Jane S. Jewish Society in Fez 1450-1700: Studies in Communal and Economic Life. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1980.

14 Chetrit, Joseph. "Juifs du Maroc et Juifs d'Espagne: deux destins imbriqués." In Lintz, Yannick; Déléry, Claire & Tuil Leonetti, Bulle (éds.). Maroc médiéval: Un empire de l'Afrique à l'Espagne. Paris: Editions du Louvre, 2014, pp. 309–311.

15 Blachère, Regis. “Fès chez les géographes arabes du Moyen Âge,” in Analecta. Damascus: Presses de l’Ifpo, 1975, pp. 541-548.

16 Al-Bakri. Kitâb al-masâlik wa l-mamâlik. Translated by de Slane. Paris, 1911. Translated also, Description de l’Afrique septentrionale. Paris, 1859. In his Masâlik, al-Bakri wants to be known as an explorer. Thus, he describes the routes and cities of the different known regions of the world in his time.

17 Le Tourneau, Roger. Fès avant le protectorat: étude économique et sociale d'une ville de l'occident musulman. Op. cit.

18 García-Arenal, Mercedes. “The Revolution of Fās in 869/1465 and the Death of Sultan ’Abd al-Ḥaqq al-Marīnī,” op. cit., 47–48.

19 Gilson Miller, Susan; Petruccioli, Attilio & Bertagnin, Mauro. "Inscrire l'espace minoritaire dans la ville islamique: le quartier juif de Fès (1438-1912)." Op. cit.

20 Rguig, Hicham. "Quand Fès inventait le Mellah," in Lintz, Yannick; Déléry, Claire & Tuil Leonetti, Bulle (éds.). Maroc médiéval: Un empire de l'Afrique à l'Espagne. Op. cit.

21 Gilson Miller, Susan; Petruccioli, Attilio & Bertagnin, Mauro. "Inscrire l'espace minoritaire dans la ville islamique: le quartier juif de Fès (1438-1912)." Op. cit.

22 Chetrit, Joseph. "Juifs du Maroc et Juifs d'Espagne: deux destins imbriqués." In Lintz, Yannick; Déléry, Claire; Tuil Leonetti, Bulle (éds.). Maroc médiéval: Un empire de l'Afrique à l'Espagne. Op. cit.

23 Cahen, Claude. “D̲h̲imma,” in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel & W.P. Heinrichs (eds). Leiden: Brill, 2006. “Bibliographie des Travaux de Claude Cahen.” Arabica, vol. 43, no. 1, 1996, pp. 264–95. JSTOR.

24 Zafrani, H. "Mallah," in Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (éds.). Encyclopédie de l'Islam, deuxième édition. Barbue.

25 Bamidbar 18:19 הברית מלח עולם היא לפני ה'. ע"ד הפשט ברית כרותה, כי מקום המלח נכרת, וכה"א (ירמיהו י״ז:ו׳) ארץ מלחה ולא תשב. ברית מלח עולם היא לפני’, “It is an eternal salt-like covenant before Hashem.” According to the plain meaning of the text the meaning is that the covenant is “cut off,” absolute, final, just like salt is cut off from the mine in which is it detached from the mother lode. The word means that something is final, irreversible. We find the word used in this sense in Jeremiah 17,6 ארץ מלחה ולא תשב, “a land so full of salt that it will never be habitable again.”

26 Rguig, Hicham. "Quand Fès inventait le Mellah", in Lintz, Yannick; Déléry, Claire & Tuil Leonetti, Bulle (éds.). Maroc médiéval: Un empire de l'Afrique à l’Espagne. Paris: éditions du Louvre, 2014, pp. 452–454.

27 Leymarie, Michel. "Les frères Tharaud. De l'ambiguïté du «filon juif» dans la littérature des années vingt", Archives Juives, vol. 39, no. 1, 2006, pp. 89-109.

28 Tharaud, Jerome Jean. Rabat, ou les heures marocaines. Paris: Emile-Paul Frères Editeurs, 1918, p. 44.

29 Gottreich, Emily. The Mellah of Marrakesh:

Jewish and Muslim space in Morocco's red city. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007.

Gottreich, Emily. Le Mellah de Marrakesh: un espace judéo-musulman en partage. Rabat, Maroc: Faculté des lettres

et des sciences humaines de Rabat, no. 16, 2016.

30 Shmulovich, Michal. "Entrevoir des souvenirs juifs au milieu des mellahs du Maroc," The Times of Israel, March 9, 2014.

31 Goldberg, Harvey. "Les Mellahs du sud du Maroc: rapport d'enquête," La Revue du Maghreb, vol. 8, no. 3, ser. 4, 1983, pp. 61-69.

32 Gottreich, Emily. Mellah de Marrakech: espace juif et musulman dans la ville rouge du Maroc. Op. cit., p. 73.

33 Gilson Miller, Susan; Petruccioli, Attilio & Bertagnin, Mauro. "Inscrire l'espace minoritaire dans la ville islamique: le quartier juif de Fès (1438-1912). Op. cit., p. 323.

34 Frank, Michael. “In Morocco, Exploring Remnants of Jewish History,” The New York Times, May 30, 2015.

35 Gottreich, Emily. Mellah de Marrakech: espace juif et musulman dans la ville rouge du Maroc. Op. cit., p. 21.

36 Gilson Miller, Susan; Petruccioli, Attilio & Bertagnin, Mauro. "Inscrire l'espace minoritaire dans la ville islamique: le quartier juif de Fès (1438-1912)." Op. cit., p. 311.

37 Gottreich, Emily. Mellah de Marrakech: espace juif et musulman dans la ville rouge du Maroc. Op. cit., p. 34.

38 Windus, John. A journey to Mequinez, the residence of the present emperor of Fez and Morocco: On the occasion of Commodore Stewart's embassy thither for the redemption of the British captives in the year 1721. US: Gale ECCO, 2018. Windus, John. A journey to Mequinez, the residence of the present emperor of Fez and Morocco: On the occasion of Commodore Stewart's embassy thither for the redemption of the British captives in the year 1721. London: Jacob Tonson, 1725.

39 Pillet, É. "L’avanie de 1716 et la suppression du consulat de Salé," SIHM France (2e série), t. VI, pp. 572-579.

40 Abitbol, Michel. Histoire du Maroc. Paris: Perrin, 2009, pp. 278-279.

41 Rguig, Hicham. "Quand Fès inventait le Mellah," in Lintz, Yannick; Déléry, Claire; Tuil Leonetti, Bulle (eds.). Maroc médiéval: Un empire de l'Afrique à l'Espagne. Op. cit., pp. 452–454.

42 Hilûla (Judeo-Aramaic הילולא, a feminine noun formed from the root הלל, HLL, the primary meaning of which is "to shout with joy and fear" is a Jewish custom of visiting the tombs of tzaddikim (i.e., the righteous) on the anniversary of their death, and commemorating their death with a festive ceremony in which the pilgrims read Psalms and other sacred or considered sacred texts (such as the Zohar).

43 Heller, Marvin J. ‘’A Fleeting Moment, A Short-lived Press: Hebrew Printing in Sixteenth Century Fez,” Sephardic Horizons, Volume 11, Issue 1.

44 Kosansky, Oren. “Reading Jewish Fez: On the Cultural Identity of a Moroccan City,” The Journal of the International Institute, University of Michigan, Volume 8, Issue 3, Spring/Summer 2001.

45 Ibid.