The Passover Scarf

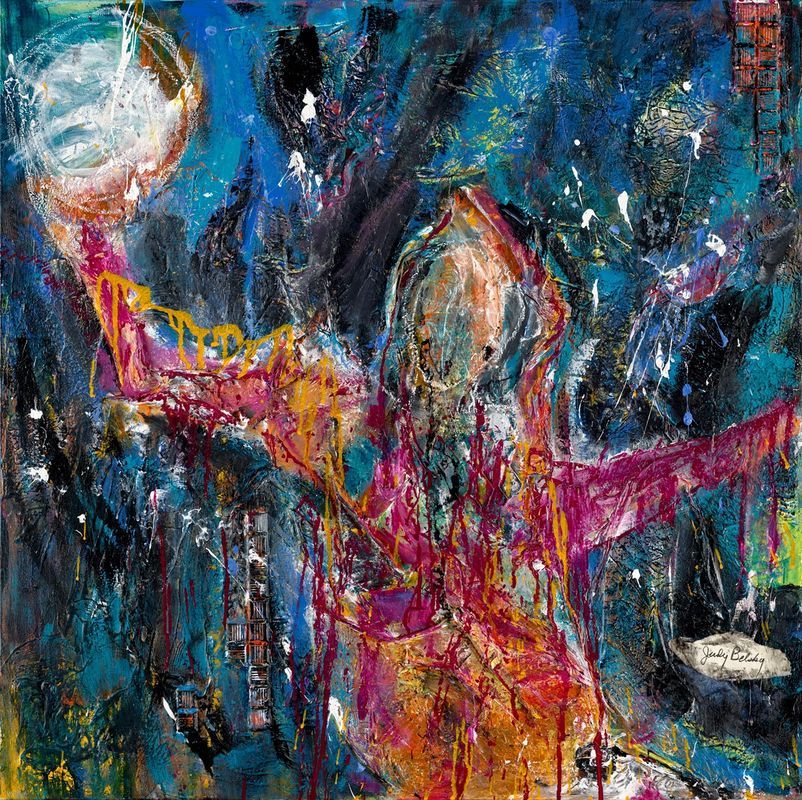

by Judy Belsky*

Miriam at the Sea. Acrylic on canvas.

Courtesy of the artist, Judy Belsky.

My first memory is fragrance. I was born in Seattle on April 8 when crocuses, snowdrops and daffodils push their tightly furled leaves past the surface of the earth. I was born with the earth’s release from a fragrance-bound winter. I was born on Passover, when my mother creates the intrigue of a new kitchen with fresh supplies and utensils.

The kitchen is the same but new. The faces peering above their dress shirts and print dresses are the same but new. The words in the Haggadah are the same but new every year when I awaken to them. There is always another Egypt to leave. My mother chops fresh spinach leaves and young leeks. She puts spinach frittata in the oven and fries leek patties on the stove. I touch the back of her neck. She murmurs into my ear, “Press harder.” My touch relaxes her tired muscle. I bury my face in her neck. I breathe deeply of her perfume. She shows me how to cook the prassa, to wait until one side is golden brown. The oil creates translucent bubbles. As I turn the patties, I misjudge where the surface of oil ends and my finger touches the hot oil. As the bubble bursts, I see my error. Pain shoots through my hand. I was so sure I knew what I was looking at. The pain in my hand brings home to me the nature of illusion. Is this how the Jews in Egypt stray? Leave their camp and follow the strange rhythms and get lost in the smoke of their offerings? What ends the illusion? Pain. Searing pain awakens them. They groan below the level of speech. That injured hand is the very one they will point with when they say at the sea: “This is my God and I will glorify Him.”

Hyacinths, blue shot through with purple, are in bloom. Hyacinthus Orientalis, originated in Turkey. Someone brought them over the ocean. I count formations of florets in the stalks until I grow dizzy, my head lolls to one side, and I lie down in the grass. Later on in the spring, the flower stalks get top heavy and fall over in our wild garden.

My uncle’s hyacinths would not dare to fall. In his garden every blade of grass, every tomato plant, every daylily and cucumber stands at military attention. They shine and thrive. I like our ramshackle garden where growth is an unexpected boon, given the benign neglect. One day I discover raspberries. Nobody knows if someone planted them or if they seeded themselves, carried in on the wind.

I help my uncle stake tomatoes one day. He takes the time to teach me how to make different knots with a bit of leftover string. Slip knot, figure eight, butterfly and a Spanish bowline. The Spanish bowline is a double-looped knot that is easy to adjust because the rope “communicates” between the two loops. If the knot is too loose, the bow will slip. I don’t know what makes the bowline Spanish. I imagine all of us with Ladino under our tongues, like fresh mint from his garden. That flavor directs our speech; we communicate between two loops of culture. If the knot is too loose, we will slip into one extreme of the loop.

My father carries pots and pans of food to the seder. The back alleyway is hung with honeysuckle like lace in the approach to a castle. In his pressed suit and gleaming white shirt, he is a prince. My aunt’s house is four doors and an ocean away. Her house is Turkish. The cool parlor is laden with Turkish rugs, brass urns, paisley throws, velvet cushion and leather footstools. Sepia photos in curved tortoise shell frames preserve the ancestors. My aunt speaks Ladino every day. My mother keeps hers for special occasions. “Pesach Alegre!” Their voices ring out with deep feeling. When they go to light the candles, my mother takes my hand to accompany her. Her veins are alive with anticipation. The code of her blood imprints itself into my hand forever. Their hands shake as they light the match. Their voices tremble when they bless the candles: “Blessed art Thou, O Lord, King of the universe who kept us alive and preserved us and brought us to this day.”

After the Seder, on the way home from my aunt’s house, I stumble, and my father catches me. It is not sleepiness that causes me to fall over my feet, nor the four small cups of wine. I am off-kilter from emotion. On this night, speech is redeemed. The crushing silence of exile is removed from us, brick by brick. Pesach breaks down into two words: peh sach, a talking mouth. Suspended between my aunt and my mother, I am mute. Too many things go unnamed. I was not born in Turkey. I don’t speak Ladino. I need to find out why I am Jewish in America. I know I am missing something, but I don’t know how dependent I am on words. My mouth does not yet know how to claim my share of the events, how to place my signature on them. I need a bridge of words to stretch between my identity and my experience. I am swamped with oceanic feelings.

The custom in our family is to take the old silk scarf edged in gold, from Turkey, wrap the matzah in it and take turns carrying it on our shoulders, reenacting the Exodus. It rests on my shoulder, an oddly light burden. I want to know how the scarf came to travel over the ocean to rest in my aunt’s oak bureau. I can’t know myself if I don’t know the story of the scarf. How the scarf is a journey, and we are not home. How, in this world, going is our home. I want to be a Journey. I want to reject a map whose destinations are too flat. I want to go out of Egypt.

Can I dare to love this scarf and not be embarrassed by it? Nobody in my school has this exotic scarf or this simple, profound enactment with which to fulfill the commandment to “see yourself as if you are going out of Egypt.” There is a powerful push to erase differences, to assimilate, to look the same. Sephardic girls want to be Americana. Ashkenazic girls want to be cool. Non-religious girls want to be goyim. All around me, there is laughter. The persistent, wordless rhythm demands: Laugh away your differences.

These words are never articulated. If they were, they might be questioned and resisted. Everywhere around me, girls follow the silent signal—Laugh! Laugh away Ladino and Yiddish and Torah and matzah and milk and meat.

And not just girls. I watch as the mothers obey the command: Laugh away the hidden Jewish woman. Laugh her out of her home and into the car. Seat her at the bridge table, the mahjong table. Portray her as a silly, bumbling, cute, irrelevant girl. I watch as they unwind her out of her head wrap, straighten her hair and the nuances of her accent. They lift her head away from Psalms. They make her laugh at her silent grandmother until one day she will leave the family album out in the sun. Figures will lose their identity, and a white halo will envelop entire families. Then she will look at the distorted image and say: how mystical, how quaint.

I am a spectator at the ruins. I sit behind a gossamer barrier, a mechitzah with gilt edges, its weave so delicate, threads pull apart.

I dream. Four Mothers visit me while I sleep. They hum with strength. Water flows from their hands as does firelight and fresh bread. The vision haunts me. I awaken hungry for their bread and thirsty for their water. Am I the only Jewish girl in Seattle in 1958 who dreams this dream?

If others do, in the morning they dismiss it. By lunchtime, they will laugh at kosher sandwiches. They will always leave for California vacations on Saturday morning. On the runway, in the last minute before take-off, a memory arises of Shabbat morning in Beit Knesset. “Adon Olam” is rising off young lips, like homage from young princes to the King. They will leave anyway. I hear the static between what they hear and what they ignore.

There is a part of me that wants to die and start over laughing. I imagine having nothing on my mind but pink Capezios, a new twin set and a circle skirt, how my hair curls, how wide I smile. I imagine putting down the burden of the matzah and melding with girls my age whose only burden is to look good and convince their indulgent parents that they are happy girls. They are always laughing and always leaving.

In some recess of mind, I realize they are on their way back to Egypt. Back to Before. Back to impression formation. Back to barely distinguishable. Back to before we are Israel, God and Torah are One.

From some perfectly preserved interior chamber, my real identity sends up messages in code. I have a recurring dream that I lose my breath, and I cannot tell anyone that I need to be saved, that my speech is stuck in Egypt. I recognize a feeling of horror as I watch something precious casually wrecked.

Once I go to the attic where an old trunk holds a cream organza dress I wore to my brother’s wedding. I think the dress is childish now, and I need a Purim costume. I imagine that I can redesign the dress, and I take my mother’s sewing shears to it. In a few seconds the delicate fabric frays, the dress is no longer a dress, but a mere limp rag.

Once I leave a favorite doll out in the backyard. Months later, I stumble against her, half hidden in the dirt and foliage, her face eaten away by weather, her once bright eyes clouded over with dust. Her dress is so worn its gingham disassembles in my hands. I could say it is only a doll.

I could laugh. But if I laugh, I am afraid I will lose myself. I might laugh myself down to the forty-ninth rung of a ladder that descends into an abyss. I am afraid if my mother kisses me, I might not taste Jewish. I am afraid to grow weak like an endangered species, an organism that sees itself as an alien. I am afraid I would laugh until I could no longer recognize my aunts, Kadoun and Luna, my grandmothers, Sultana Vida, Ledicia or Judith.

Judith is my name.

If I begin to laugh, I might forget my name. I might laugh until I am less than one-sixtieth of myself, a rough estimate of how much it costs to give away five thousand years.

These unnamed feelings press on the veins of a Passover child. Who am I? How will I go out of Egypt if I do not know who I am? If I do not know who I am, maybe I will refuse to go out of Egypt. Maybe when the Redemption comes, I will be left behind—a mute, abandoned doll. Laughter obscures the borders where Egypt begins and ends. Every year at the Seder, I see visions of seas to cross, deserts to survive, promised lands to travel toward. God to worship. To crown Him King, I have to stretch above my head. To make Him King, I have to awaken from the hypnosis of culture and resist the laughter. In the silence, I imagine I can hear the rhythm of His Breath. Desire washes over me like an ocean swell. This Passover child can be soothed only with words. Who can find the words to feed my hungry heart?

At the Seder as we recite the Haggadah and take turns carrying the matzah, I imagine that above our heads hovers a girl wrapped in yellow silk. No one else can see her. Can I reach up for her and carry us both out of Egypt?

In an age of extreme conformity, I am left holding a scarf.

* Judy Belsky is a writer, artist and clinical psychologist. She lives in Israel. She has published a memoir and several volumes of poetry. One of her main themes is her Sephardic background in Seattle, Washington. A second memoir in progress is entitled The Passover Scarf.