Kerem Tınaz and Oscar Aguirre-Mandujano (editors)

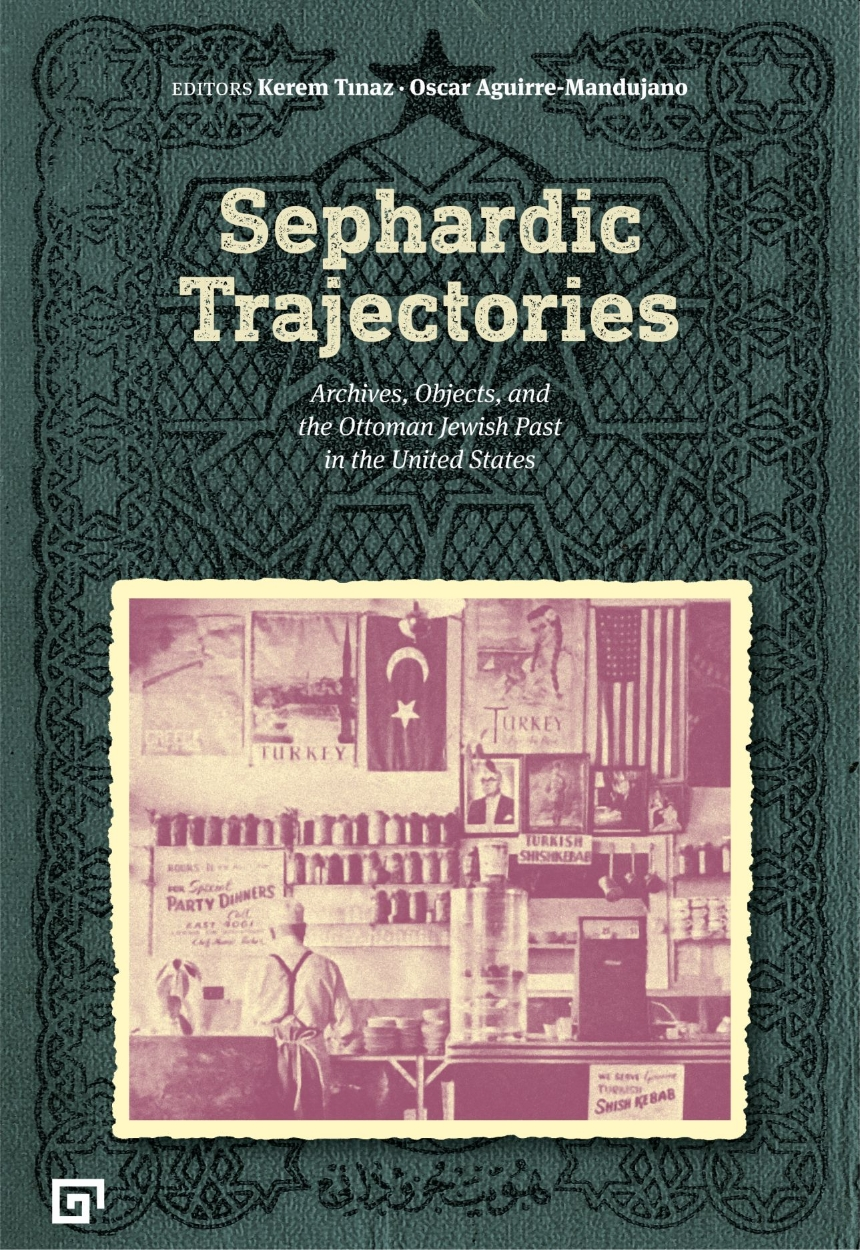

SEPHARDIC TRAJECTORIES: ARCHIVES, OBJECTS, AND THE OTTOMAN JEWISH PAST IN THE UNITED STATES

İstanbul: Koç University Press, 2021. ISBN: 6057685369

Reviewed by Semih Gökatalay1

Sephardic Trajectories is a collection of nine essays arranged in three parts with an introduction. The focus of this book is the University of Washington Sephardic Studies Collection (UWSSC), which offers an impressive quantity of new material on Sephardic Jews, even though not all the chapters are based on these archives or are about Sephardim. Under the leadership of Devin E. Naar, the Isaac Alhadeff Professor in Sephardic Studies at the University of Washington, a team of scholars and researchers uncovered evidence of a thriving culture of Jews from the Ottoman Empire and its successor states who settled in Seattle. Sephardic residents of the city and surrounding areas donated an amazing collection of texts and artifacts that belonged to their families to the Naar-led team.

The Introduction by Oscar Aguirre-Mandujano and Kerem Tinaz sets the stage for the book. They address the need to explore Ottoman Sephardic culture beyond the limitations of the Ottoman Empire and the nation-state by looking at the transnational characteristics of Sephardic migration. Further discussed is the role of private collections, local communities, and digitized archives in shaping the scholarly understanding of the past.

In Part One, the formation of the UWSSC is detailed. Naar provides a detailed study of the experience of Ottoman Jews in Seattle in Chapter One, “Ottoman Imprints and Erasures among Seattle’s Sephardic Jews.” Building on the insights of his previous studies on the Sephardic migration from the Balkans and the Middle East2 and engaging effectively with the social or political aspects of the United States, he elucidates the evolution of Sephardic identity in the first decades of their migration to the Americas. Although many Jews preserved their Ottoman identity in the early twentieth century, the American entry into World War I against the Ottoman Empire and the partitioning of the latter profoundly transformed the self-designation of Ottoman Jews. They actively sought to fit into the fabric of American society in the following decades.

Ty Alhadeff in the next chapter, “The Seeds for a New Judaeo-Spanish Culture on the Shores of Puget Sound,” explains the formation of the UWSSC and its importance for the study of Sephardic history. He points out that contrary to the richness of digital sources in Yiddish, only limited archives and collections of Judeo-Spanish sources exist. The opening of this collection, thus, has presented scholars with a unique opportunity to delve into the history of Sephardic life in the United States, albeit mostly in the Pacific Northwest. Its holdings include communal records, correspondences, family letters, Judeo-Spanish novels, postcards, photographs, prayer texts, travel documents, and visas. According to Alhadeff, an examination of these sources, or in his words “crowdsourcing the past” (pp. 83-84), not only sheds light on the material culture of Sephardic Jews in the United States but also challenges the orientalist assumption that Ottoman Jews were not part of universal cultural trends in Judeo-Spanish.

Examples of how the UWSSC has brought original approaches to the past of Ottoman-originated Sephardim are presented in Part Two. Maureen Jackson in Chapter Three, “From the Aegean to the Pacific: Ottoman Legacies in Seattle Sephardi Synagogues,” presents a lively picture of the emergence of Seattle as a cultural center for Ottoman Jews. While many studies of Sephardic culture in the United States have focused on Spanish-Portuguese Jewish institutions in New York,3 Jackson convincingly illustrates the development of a novel culture by Ottoman Jews in Seattle, as evidenced by Ottoman-style liturgical music and prayer books. Specifically, she discusses the role of music and prayerbooks to unify the Sephardic communities in this city.

In Chapter Four, “Walking Through a Library: Notes on the Ladino Novel and Some Other Books,” Laurent Mignon provides a comprehensive overview of Ladino literature in the late Ottoman Empire. In contrast to the conventional wisdom that ruled out the development of Sephardic literary traditions, he redresses the growth of new genres and readership among Ladino-speaking communities in the empire. National consciousness and Zionism created the political space for the growing popularity of historical novels among the Ladino literati.

A nuanced picture of the link between military service and non-Muslim subjects in the closing decades of the Empire is sketched by Özgür Özkan in Chapter Five, “Sephardic Soldiers in the Late Ottoman Army.” Using a rich trove of primary and secondary sources, Özkan argues that the number of non-Muslim soldiers, especially high-ranking officers, was much higher than previously supposed. The discovery in this archive of the diary of Leon Behar, who was an officer in the Ottoman army, illustrates the emotional fervor and nationalistic pride that a series of wars inspired in Ottoman Jews. Özkan concludes that this manuscript proves the significance of non-traditional archives for the study of Ottoman Jews.

Additional benefits that private collections and family memoirs bring to the students of the Ottoman Empire are examined in Part Three, even though the articles in this section do not necessarily draw on the UWSSC. Benjamin C. Fortna addresses the contents of the trunk belonging to Kuşçubaşı Eşref in Chapter Six, “Artifacts and their Aftermath: The Imperial and Post-Imperial Trajectories of Late Ottoman Material Objects.” Eşref was an influential special agent who worked for the Ottoman state in the waning decade of the Empire. Fortna explains how the private collections influenced the research for his book on Eşref.4 He asserts that the use of such sources can help historians correct prevailing narratives that are determined by state archives and traditional sources.

I found the essay by Chris Gratien and Sam Negri, Chapter Seven, “Deporting Ottoman Americans,” to be arguably the most interesting part of the book. Gratien begins with an excellent discussion of the life of Leo Negri who migrated from the Ottoman Empire to the United States. His subsequent deportation from and reentry to the United States is discussed within the broader framework of migration and race in American society in the interwar period. Leo was only one of the thousands of immigrants who faced significant challenges in obtaining visas. Next, Sam Negri, a son of Leo Negri, offers his personal experience as a person of Sephardic heritage in Brooklyn. He shares his encounters with mainstream Jewish culture that was dominated by the Ashkenazim.

Chapter Eight, “Amid Galanti’s Private Documents: Reflections on the Legacy, Trajectory, and Preservation of a Sephardi Intellectual’s Past,” by Kerem Tinaz, traces the story of Avram Galanti, a well-known Turkish Jew. Galanti’s life was emblematic of the different trajectories of Ottoman Jews who moved to various parts of the world in the early twentieth century. Tinaz makes judicious use of the private documents found in Israel about Galanti; he links them carefully to secondary literature on Ottoman and Turkish Jews.

The final chapter, “Galante’s Daughter: Crafting an Archival Family Memoir,” by Hannah Pressman undertakes an in-depth exploration of the life of her great-grandparents. As with Sam Negri, Pressman provides a striking account of the experience of Sephardim in the United States. She gives invaluable information about her project-in-progress that elaborates on her family history within the broader schema of modern Sephardic identity in the United States.

Sephardic Trajectories represents an exemplary mix of sources and creative thematic structure. A number of prominent researchers were assembled to contribute to the study of the lives of Ottoman Jews after the end of the Empire. This book further stands out for its novel treatment of private collections and their use in compiling the history of Sephardim in the United States. Another strength is the insightful analysis of the global context in which Sephardic migration and integration into American society took place.

One major problem with this book is its broad subject matter. Although the title refers to Ottoman Jews in the United States, not all chapters deal with this issue. Indeed, Fortna’s chapter is not even about Ottoman Jews but about a person of Circassian background. Furthermore, the structure of the book gives the reader a segmented feel, perhaps more than an average edited volume of this magnitude. The contributors could have explained the content of the UWSSC in more detail, especially since the introduction promises to emphasize this collection. For example, the author of Chapter One could have taken a closer look at the potential benefits of the UWSSC for amateur and professional researchers. One might have expected him, as the driving force behind this project, to provide more insights into the richness of this unique collection.

Despite this criticism, there is no doubt that this volume and the novel sources that it introduces will inspire future works in Sephardic studies. Researchers who are interested in the Sephardim will certainly find value in this book. The large swath of materials from the UWSSC and the revisionist approaches of the authors will become an invaluable tool for Sephardic scholars, in general, and historians of Ottoman Jews, in particular.

1 Semih Gökatalay is a Ph.D. candidate in history at University of California, San Diego. His dissertation in progress is a political and economic history of the modern Middle East during the transition from the Ottoman Empire to nation-states.

2 For example, see Devin E. Naar, “From the ‘Jerusalem of the Balkans’ to the goldene medina: Jewish Immigration from Salonika to the United States." American Jewish History 93, no. 4 (2007): 435-473; Devin E. Naar, “‘Turkinos’ beyond the Empire: Ottoman Jews in America, 1893 to 1924,” The Jewish Quarterly Review 105, no. 2 (2015): 174-205.

3 For example, see Herman P. Salomon, “KK Shearith Israel’s First Language: Portuguese,” Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought 30, no. 1 (1995): 74-84.

4 Benjamin C. Fortna, The Circassian: A Life of Esref Bey, Late Ottoman Insurgent and Special Agent (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).