My Uncle: A Memoir of Postwar Hungary, Italy and Israel

by Israel Rodolfo Lichtner1

I have seen my Uncle only three times.

Actually, he had seen me two more times previously, but I was little more than one year old, and cannot remember.

He arrived suddenly after having disappeared for four long years. Nobody knew whether he was still alive.

He arrived at dawn in the house where I was born, in via Pontedera, a little street with just two buildings, in Rome, near the place where the Beth El is now, the Libyan Shul that replaced my movie theater where, as a child, I used to watch Western films. My house was number 5, had four floors and some gardens around, and I lived on the fourth floor. In the flat next to ours lived Mrs. B., who according to my mother had received German soldiers during the occupation, and maybe had informed on my father when policemen came to look for him. In the flat under ours there was Mrs. P., who had helped my father to escape, climbing down from his balcony with a rolled sheet. I routinely met both ladies in the elevator.

It was a beautiful and strong house with thick walls and balconies with wrought iron railings. There was a long L-shaped corridor on which all the rooms opened their doors. In that corridor I launched my toy cars.

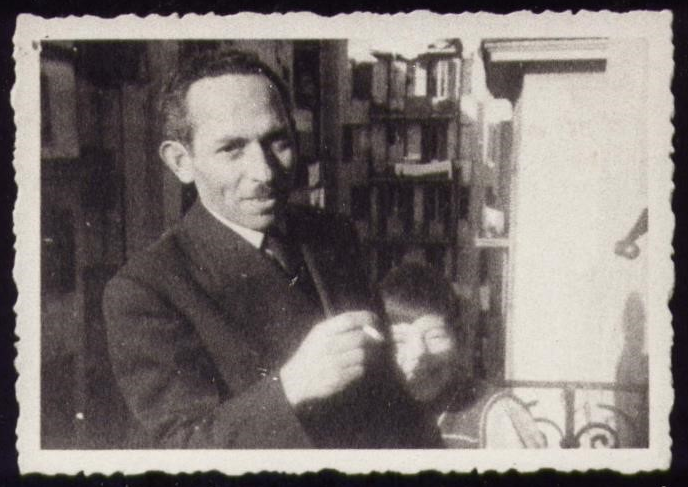

Babbo and I in the via Pontedera balcony, 1952

My Uncle rang the doorbell and the housekeeper opened, while we were still asleep. The poor woman drew back in horror in front of that view: she saw a man terrified, worn out, ragged, dirty and unshaven from his long travel on foot. She tried to push him out, but he forced his way in, and searched all the rooms until he found the one where my parents were sleeping.

My mother did not know him. She told me that she had heard both brothers screaming and crying in their stranger language. She was terrified.

At home he was called the Uncle David, always with the article, while letters were arriving in Hungarian signed by Dezső, his Hungarian name. The other (maternal) uncles and aunts who lived in Italy were instead just called ‘Uncle’ and ‘Aunt’ without the article.

When their wailings were at last translated, it was understood that my father kept insisting:

“It’s not possible that they are all dead! Someone must be left alive!” while the Uncle kept saying: “No, there is no more!”

He was talking of my grandmother Anna Golda, of their other five brothers (they were seven brothers, my father was the sixth one and my Uncle David the fourth or fifth one) and their families, including Uncle David’s wife and children.

Like many other Hungarian Jews, Uncle David had been enlisted in the army when, in 1941, Hungary had invaded the Soviet Union, but not to fight, rather to work, unarmed, on the front, in the hands of a pack of torturers with full powers. Forced to dig trenches the whole day, in the Ukraine’s frozen earth, with hardly any food, every time he fell to the ground out of exhaustion, a tooth or a nail was extracted as punishment, until there was nothing left to extract.

The Jews enlisted to the front died at 90%, but my Uncle found a way to save himself. During a Soviet offensive, he ran in the opposite direction, and ‘surrendered’. They sent him to a prisoner of war concentration camp in Siberia.

When the war ended, the Russians did not show any willingness to set their prisoners free, but my Uncle did not give in; he wanted to find his family that he had left back home, in Miskolc, in Eastern Hungary.

I don’t know how, but he managed to escape from the camp. He started to walk, and kept walking for thousands of kilometers, eating whatever he could find, until he reached Hungary.

The town was in ruins. It had been largely bombed by the Soviets during their advance in the winter of 1944-45. Before they arrived, the Hungarians had seen to it that all the Jews be arrested and delivered to the Germans to be carried away by train.

He searched through the ruins, found his own house’s ruins, his mother’s, his brothers’; he found no one. All that had lasted was Grandfather Moshe’s tomb in the city’s Jewish cemetery. My grandfather had died five years before the war started. This I found out when I was already grown up, because when I was a child I was told that both my grandparents had died because of the war.

Someone who had known them in the city confirmed: all had been carried away and none had returned.

Uncle David did not lose heart: he took to the road again, still walking. Other relatives were in Eger, Budapest and other Hungarian cities, maybe they were alive. There too he found nobody.

Uncle Bela, the youngest of the seven brothers, inscribed picture from Miskolc,1941

His last hope was to find his brother Gyulá (Giulio, my father), who since 1923 had moved to Italy.

In 1918, with the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire caused by Italy’s surprise aggression, nationalism and anti-Semitism had spread through the new independent states, which started to approve laws limiting Jews’ power in their territories. Young Gyulá, the sixth of Moshe’s and Golda’s seven sons, had left when he was just eighteen years old, after finishing his Classical High School in Miskolc, because the universities of independent Hungary no longer accepted Jewish students. He had to choose between Germany and Italy and chose Italy, although he did not know one word of Italian, and had to study with a dictionary.

After his medical degree, in 1930, he had decided to stay in Rome, and had not come back to Hungary but for short summer vacations, traveling by hydroplane.

David decided to try: maybe Gyulá had escaped the extermination.

He crossed the Alps on foot, crossed frontiers, reached Rome, found the street, found his brother, and with him his two children, the only ones left of the new generation.

I was born one year earlier, shortly after Rome’s liberation, and my father, back home from hiding, had helped deliver me in our home in via Pontedera where there was no electricity; he worked in the dark, but at two a.m. the light came back and I was born.

Uncle David remained in Rome for some time. He was fed and cared for. A little dwelling was set up for him in our attic, on the fifth floor of our building. My father used to give him a little money for the day, and he came back home with chocolates for us children, having spent nothing for himself.

It was soon clear that he had no chance of finding a job in Italy, where he did not know the language and had no visa, and as he could not go to any other place (Palestine being still forbidden to survivors by its British occupants) he had to accept to go back to Hungary, where he could start his old job again, trading cloth as my grandparents had done.

Still on foot, as trains had not been restored yet, he reached the border with Austria. Along the way Jews were walking, extermination camp survivors, some of them trying to reach Italy and there later embark, illegally, to reach the land of Israel.

Among that crowd he met the woman who was to become his second wife, Janka (Anna) Kornauter bat Yitzchak, also from Hungary, a survivor of Auschwitz and the butcher Mengele’s experiments that had made her barren.

Janka had no intention to head back East, where she had suffered all those years at the hands of the Hungarians first and the Germans later. So she convinced him to go back to Italy.

On the 8th day of Kislev 5707 (December 1st, 1946) David and Anna married in Rome’s Great Synagogue. They were married by Rabbi Isacco Vivanti, who was also their witness.

Unfortunately, this time too they had to leave, and so my last chance of growing up with my Uncle David vanished.

Of course, nobody knew that within one year Hungary would be separated by the Iron Curtain and it would no longer be possible to go and see the Uncle, nor for him to come back and see us.

For twelve years ,the only contact with the Uncle were his long letters written in that incomprehensible language riddled with accents, and to me just the news came that “the Uncle David has written,” along with nice stamps for my collection. I was told nothing else about him, but from conversation and face expressions I understood that he was not getting along very well.

At that time my father, whom I called Babbo, after all the suffering at the hands of the Fascists, was attracted by the Communists, and was convinced that life was not too bad in the countries under Russian occupation, and that the Uncle’s problem may be due to his inability or his obstinacy in not cooperating with the regime. Even at the time of the 1956 revolt, he still believed the official version, that the revolt had been staged by the Fascists with West German help.

It must be told that Uncle’s letters went through censorship as much as they had done during the war, so it was difficult to realize the real situation.

Thus my Uncle saw me at the time of his wedding.

Eyes were opened when in 1958, at last, the Uncle managed to get a visa and landed in Rome. By that time we had moved to a house with large terraces in via Lanciani. After new long discussions, Babbo translated, in his usual concise style, “He said that one cannot live in Hungary, as Hungarians are all Fascists.” That was what he believed at that time.

I was fourteen, and did not feel much in confidence with the newcomers, who were very loving, but talked in an unintelligible way, so I could not communicate with them much.

My Uncle was a man almost as little as my father, and rather similar to him. He looked nice.

A few days later Uncle and Aunt left on Aliyah to Israel.

I did not know whether I would see them again, and at that time nobody at home ever talked about traveling to Israel. As boys, we were sent to England and France to learn languages, and to Spain for a holiday, where we also learnt Spanish, but going to Israel or learning Hebrew was not in the family’s plans.

At the same time, Babbo refused to teach me Hungarian, saying I would never have a chance to use that useless language in my life.

My Grandparents and my six Uncles

Four years later, while I was studying for my High School diploma, my brother, three years older than I, came home from university, where he was studying philosophy, with something new: he had found an advertisement that a Greek cargo ship was going to carry passengers on the deck for little money from Venice to Haifa. This news opened a whole new world to me and I started to read about Israel. We were able to go with our own savings, without asking our parents; nobody raised any objection.

So we embarked with our sleeping bags, backpacks and camp beds and, lying under the sun in the middle of a few dozen passenger-campers, sailed to Piraeus, then Rhodes, Famagusta and at last, after a week, Haifa. I was moved when I first saw the Carmel coastline.

We had made ourselves an ambitious travel plan that in one month would let us see the whole of Israel, from Upper Galilee to Eilat, hitchhiking the whole way. We worked on the grapefruit plantations in the Nir David Kibbutz, not far from the Kinneret. We reached Jerusalem, where we slept in the Hebrew University’s student accommodation, then Be’er Sheva, then at last Dimona, the new desert city where the Uncle David had come to live.

The town was made of low, long houses, all lined up. We found the Uncle’s address (I don’t remember what it was). Uncle and Aunt were waiting for us with enthusiasm, they were happy to have us as their guests, at last. In their building, and in the buildings nearby, there were recently arrived Jews, mainly from Hungary and Romania. They called a neighbor who knew both Hungarian and Romanian, and asked him to translate for us, as Romanian is more easily understandable to Italians than Hungarian.

I must say that I did not assign that historical meeting the importance it deserved. I had reached the age of eighteen in Israel, and had only recently freed myself from the constraints of my Italian relatives, and the last thing I needed at that time was to find additional relatives.

It was a simple home, but it possessed more the character of a Central Europe house rather than an Israeli one, although it had not yet become that perfect little mittel-European home that I was to find during my second trip. From outside, however, it could not be distinguished from the other pioneer houses of the town, later to become famous for its nuclear plants.

The Uncle David took me to visit the factory where he worked. It was a textile factory, wholly automated, and his task was to keep watch over the machines, and brush the moving threads that would show any part out of place.

Uncle David and Aunt Janka in Tel Aviv, 1973

Now the letters were arriving from Israel, no longer from Hungary, but still full of incomprehensible accents, and still stamped with beautiful stamps. Three years after my trip to Israel, I left my parents’ house to get married, so even the Uncle’s news reached me less often. Anyway, Babbo, who had given up Germany’s compensations in favor of his brother, kept sending him dollars, and my Uncle used to send chocolate boxes and other Israeli sweets.

Sometime later, my parents started to regularly travel to Israel. My father had found a schoolmate again, who was an ophthalmologist, and had asked him to treat my mother’s glaucoma. So they were often going, and my Uncle was traveling from Dimona to Tel Aviv to meet them.

Meanwhile, my first three children were born. We used to travel often and were taking the children with us to all parts of the world. At a certain time the idea was raised to go and see the Uncle together with my parents. So we went on a journey, stopped over in Tel Aviv and in Jerusalem, where I could visit the recently conquered Old City for the first time, and see the Kotel, that my father was particularly fond of visiting. He explained to me the meaning of the Kotel for the Jews during the long centuries of exile. Babbo was very afraid of the Arabs in the narrow lanes, but I did not realize the danger and thought he was going too far.

We went to Dimona. The house was not the same – or it had changed, even outside. The town had grown very different, was inhabited by Jews of the most diverse origins, even from India. On the stairs of the Uncle’s house, women and children were eating on the steps and chatting, the doors to their flats left open. But when we entered the Uncle’s home we found ourselves in another world. The home was filled with food, the table set with great plenty and with great care for the Shabbat.

We were getting ready for the dinner. My Uncle sat down and took my eldest son Giulio, then little more than five years old, on his lap. On a shelf, among other pictures, there was a photo of a boy about his age, and very similar. My mother told my wife: “Please tell Giulio to let the Uncle do as he pleases, not to shirk him, as he is thinking of his son.” Giulio patiently sat on the lap of that unknown aged man while he silently recited his blessings. For some reason that I don’t know, he did not do the same with my other children.

After spending some time at the Uncle’s, we planned a trip together. My parents and my wife had not seen the Dead Sea before, so we decided to visit the Ein Gedi waterfalls, which I remembered pleasantly from my previous travel, when I had reached that then backwater location on a military lorry and had slept under the soldiers’ tents.

The Uncle came with us, while the Aunt remained at home. We had hired a car with an Arab driver. Once arrived at Ein Gedi, we climbed the sharp hill, with the children on our necks. When we saw the beautiful little pools fed by the waterfalls, bright under a gleaming sun, the children wanted to dive, and I myself wished for a good bath. So we took off our shoes and entered the water, while my wife cautiously remained on the dry ground, keeping the bags. My Uncle had remained somewhat behind and was not in sight. At that time he was about seventy-five, and it was already surprising that he could have managed to reach that high place. My father was seventy.

At that very minute we heard a huge rumble, a noise similar to the one evoked by the victims of earthquakes. The sky was still bright and blue, and the water was still cheerfully running, but we understood that something was happening. An instant later large and small stones started to rain down on us like at Sodom and Gomorrah.

We looked for shelter as best we could, but stones were falling everywhere. Together with the stones, water kept falling from the falls, suddenly enlarged tenfold. We went out of the water and climbed on a rock. At our side a stream was running fast towards the valley, carrying everything in its path hundreds of meters downstream towards the Dead Sea.

In that stream suddenly I saw my mother falling; not finding a hold, she was about to be carried away by the water. I went down the rock and grabbed her neck, holding strongly until I felt she had stopped, then slowly helped her to climb on to the rock.

While we were in vain trying to shield ourselves from the flying stones, we were wondering what had become of my Uncle, but we were unable to move. Babbo was praying.

After some time, while the flood was not showing any sign of decreasing, we saw a soldier coming our way. Having heard what was happening, he had rushed up from the kibbutz. With him there was the Uncle. The soldier showed us an escape way that we had not seen, on the opposite side, towards the mountain. He helped us to cross the stream and reach the dry rock. All the tourists were lined up and driven through a long mountain path, which after having climbed up for a while, went down to the road and the car waiting for us. The children had walked that entire route in swimming wear and with bare feet.

We asked my Uncle how he had managed to save himself. As he had seen the water flood the path, he had climbed up a tree. A German woman had helped him to climb. He did not look exceedingly tired or scared.

The day after, we left for Sharm El-Sheikh, that was Israeli at that time.

About five years later, unfortunately, my Uncle left us. He had undergone surgery for a minor disease; the surgery ended without problems, but he did not wake up.

Babbo, who had had surgery several times, and was fighting for his health every day, was deeply stricken by that unexpected death due to such a trivial reason as anesthesia.

Babbo went on his own to bury his brother, the only member of his family left. He asked nobody to go with him. He saw to everything and helped the widow settle at Kibbutz Negba where her nephew Izchak Mermelshtein lived, at Lakish Tzafon near Ashqelon, where I had worked on the apple trees during my first trip. She soon stopped sending her news, and nothing was known of her death, that likely shortly followed her husband’s. Many years later, when my father was no more, I went back to Dimona with my wife to look for Uncle’s tomb, but we could not find it.

Shortly after my Uncle’s death, there was an event that nobody could foresee, and that seems unbelievable. One evening we were at my parents’ home, and Babbo was busy in his medical ambulatory, which was in another wing of their large house, while we were waiting for him in the kitchen. Then my father appeared with a devastated look, like one who has just seen a ghost. “A man came to my studio;” he told us, “he said he is Zoltan’s son.” Zoltan was the first-born of the seven Lichtner brothers, and had been deported to Auschwitz together with his son. The son had survived.

After the war the boy (I don’t know his name) had gone back to Hungary and had committed himself to work in the Communist Trade Unions. He never could get in touch with his relatives, probably to avoid being accused of treachery (it was forbidden to have relations in ‘Capitalist Countries’). That time only he had made an exception, he had come to see his Uncle, whose address was in the telephone directory, but had had to go away soon, and had not wished to see the rest of the family.

When Babbo turned eighty, he wanted us to sit in front of him and listen to him, including our children – the youngest being seven. After a long and circuitous introduction about the need to be true to one’s roots, he reached the message that he wished us to receive: Remember – he said – that there is always Israel: when you need it, it will be there for you.

© Israel Rodolfo Lichtner 2011 תשע"ב Updated 2019 תשע"ט

1 Israel Rodolfo Lichtner was born in Rome, Italy, just after the city was liberated by the Allied Armies. He is now a painter and ceramicist based in Rome and Pitigliano, Italy, after retiring from a fifty-year career as a computer engineer across Italy, the UK and the USA. As a translator into Italian, Israel has published a Haggadah of Pesach and four chapters of the Talmud. In 2012 he made aliya to Israel and lived two years in Jerusalem.