Hélène Jawhara Piñer

SEPHARDI COOKING THE HISTORY, RECIPES OF THE JEWS OF SPAIN AND THE DIASPORA, FROM THE 13th CENTURY TO TODAY

Brookline, Ma.: Academic Studies Press, 2021, ISBN 9781644695319

Reviewed by Annette B. Fromm1

Cookbooks are often considered works of literature as well as practical guides to a certain type of food. Many consumers whether they cook or not, read these compendia as they would take in a history book. Of course, the primary function of a cookbook is to be sourcebooks of recipes, sets of instructions to prepare particular dishes. They are organized around a particular ingredient, food from a particular country, or recipes reflecting an ethnic group. I read this new set of recipes from the point of view of the content because of my interest in Sephardic cultural heritage and food traditions. I also read them to see which I could add to my culinary repertoire; I actually followed several recipes and prepared the dishes.

As in many cookbooks, the recipes are organized into several different groupings. One is according to the key ingredients or a part of the meal, such as Bread and Snacks, Vegetables and Eggs, Eggplants, Meat and Fish, Soups, and Desserts and Pastries. A few other groups of recipes are grouped according to the requisites of the Jewish calendric holidays, such as Yom Kippur.

Others are placed together by specific historic sources, Maimonides’ Regime of Health and two medieval Arabic cookbooks in particular. Finally, the book is closed with recipes that the author, who holds a doctorate in medieval history and the history of food and is a trained chef, constructed based on her readings of the multiple sources. This final selection is the author’s modern contribution to Sephardic culinary arts. They reflect two basic elements that have been identified as significant in this historic canon: adaptation and evolution. Jawhara Piñer creatively brings together ideas which draw upon her family’s practices, her travel experiences along with her favorite foods, and other influences.

Reflections drawn from her extensive research briefly preface two sections of the book. The other sections are introduced with related excerpts from the Maimonides book or, in one instance, quotations from inquisition trials. Additional, specific information is briefly provided along with each recipe, placing them specifically with one of the medieval books it was drawn from and trial records in which it might have been referenced.

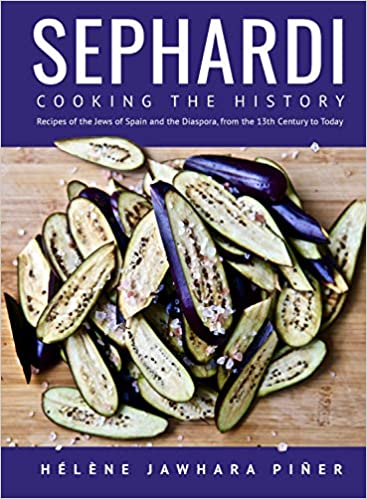

Jawhara Piñer’s aim is not only to provide a historical record of Sephardic foods in the Middle Ages, but also to provide a sense that these dishes have continued to be prepared and enjoyed over the centuries. Accordingly, the foods represented in this beautifully illustrated book stand out because of several elements. Primary clues she sought were how the dish was prepared, if it was prepared for a particular celebration, and the ingredients used in preparation. Her sources did not often reveal quantities of the ingredients; her frequent testing led to what is presented in the book. Thus, many of the recipes, as the author notes in the introduction, are reconstructions.

Perhaps Sephardi Cooking stands out from other cookbooks as a historical document. Sources of recipes, which the author thoroughly researched, include three thirteenth and fourteenth century cookbooks, two in Arabic and one in Catalan. Other sources included the Maimonides’ Regime of Health, already referred to, and trial records from the inquisition in Spain and Mexico. The end result is not only a collection of dishes, but also an understanding of old culinary techniques, that she specifically identifies as Jewish.

A number of shortcomings and inconsistencies are found throughout the book. As a reader interested in the culinary and social history, I came away with only brief hints to either. Two pages are allotted to most recipes; in many cases, the text and recipe face a full-page, attractive photo of the finished dish. I had the impression that this format and design, while beautiful, constrained Jawhara Piñer from adequately sharing more information drawn from her medieval cookery sources or the individuals subjected to inquisition trials. She frequently references two Arabic books in some of the brief introductions to the recipes. In addition, she refers to a twelfth century cookbook from Cairo and another from thirteenth century Syria. As this cookbook, however, is a reflection of her extensive research, more additional in-depth information about each of these obscure books in the introductory text would have satisfied the cookbook reader in me.

As a home cook, some details were found to be lacking or confusing. A Swiss chard stew with meat and chickpeas, acelgas con garbanzos, (pp. 40-41), is a dish Jawhara Piñer found mention of in at least one inquisition trial in 1590. She also attributes one of her grandmothers as the source of the recipe in the book. It is not difficult to follow and results in a quite light stew. One ingredient listed as “beef steak,” however, is much too general; a more specific cut would have been helpful.

Instructions to cut carrots and celery “the width of two fingers” in puchero, Maimonides’ chicken soup (pp. 98-99) are unusual. An inch or centimeter measurement is a more standard cookbook direction. I wondered about the source of the name of the dish, puchero, and what it is called in Maimonides’ work. A quick internet search of each reveals very different versions of this soup, none with a poached egg as per Jawhara Piñer.

Eggplants, having long been identified as a food eaten by Jews and Muslims in medieval Spain, figure large in many of the recipes. Another recipe that I prepared was the cacuelas, Eggplants with saffron and Swiss chard for a Converso wedding (pp. 50-51). Three eggplants are sliced into rounds. They are then to be “put ... in the frying pan so as to form one layer only, not overlapping” (p. 51). There was only room for the slices of two small globe eggplants in my 16” frying pan. Perhaps Jawhara Piñer should have identified the type of eggplant to use.

A number of the recipes in Sephardi Cooking, taken from the medieval Arabic cookbooks according to Jawhara Piñer, refer directly to Jews. The third dish that I cooked, “Meatballs Cursed by Jews” (pp. 66-67),2 is one. Jawhara Piñer cites two editions of the same cookbook, Waṣf al-aṭʿima al-muʿtāda, as the origin of the curious name or “title” of the dish. According to her, “cursed” appears in an earlier edition, not in the seventeenth/eighteenth century version. Newman, however, writes that the fourteenth century edition “includes a recipe for ‘Jewish meatballs’” (Newman 7). “Meatballs Cursed by Jews” is a relatively easy preparation of beef meatballs enriched with chopped parsley, mint, and celery leaves. The recipe calls for one pound of “beef ground meat” and promises to yield twenty-five meatballs the size of walnuts. I was able to make fourteen following the guidelines.

Finally, several recipes including two for “Jewish” partridge (pp. 58-60), direct the reader/cook to decorate the finished dish with hardboiled eggs placed around the bird in a six-pointed star shape. Material culture from medieval Spain is scarce. The six-pointed star does not appear on any extant item. In fact, it was not used as a Jewish symbol until 14th century Prague and did not gain widespread use until the 19th century.

In the past year, Jawhara Piñer has demonstrated a number of the recipes found in the book to worldwide audiences via zoom. They were often not very veiled promotions for this cookbook. One of the first zoom cooking classes that I watched was for the so-called “Bread of the Seven Heavens,” the first recipe in the book (https://vimeo.com/421610083). She writes about the lack of early references to this particular bread in either medieval written sources or inquisition records. It has recently been attributed to the Jewish community of Thessaloniki in the popular press. Her inventive reconstruction would have been better presented in the final section of the book.

Sephardi Cooking the History is a beautiful, easy to read cookbook full of distinctive recipes whose origins are traced to medieval Spain. The author not only has been able to trace many of the origins to Arabic cookbooks of that long ago time, but also adapt them for the modern cook, albeit with a number of inconsistencies. The book’s foreword was written by the late David Gitlitz, who, with his wife, paved the way with their (cook)book, A Drizzle of Honey.3 Jawhara Piñer represents a group of young scholars and cooks who are rediscovering their heritage.

References:

Newman, Daniel L. (2017) Book reviews: Charles Perry (ed./trans.), Scents and Flavors. A Syrian Cookbook, Library of Arabic Literature (New York, New York University Press, 2017). Catherine Guillaumond (trans.), Cuisine et diététique dans l’occident arabe médiéval d’après un traité anonyme du XIIIe siecle. Étude et traduction française. Préface d’Ameur Ghedira, Histoire et Perspectives Méditerranéennes (Paris, L’Harmattan, 2017). Food and History, 15 (1-2) (accessed on-line 14 December 2021).

1 Annette B. Fromm is a museum specialist, folklorist, and lecturer in Romaniote and Sephardic studies and associate editor of Sephardic Horizons.

2 More detail on this dish than appears in the book can be found at https://momentmag.com/jewish-meatballs-talk-of-the-table-meatballs-cursed-by-jews/.

3 David M. Gitlitz and Linda Kay Davidson, A Drizzle of Honey, The Lives and Recipes of Spain’s Secret Jews, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999.