Moses ben Baruch Almosnino: A Sixteenth Century Multi-Faceted Sephardic

Sage in Salonika1

by Marvin J. Heller2

R. Moses ben Baruch Almosnino (c.1515-c.1580) is among the foremost sages of Salonika in the sixteenth century. A multi-faceted eclectic scholar, well known in his time and highly regarded in rabbinic and academic circles today, he is barely remembered by the general population. This is especially regrettable as he is frequently referenced in academic literature.3 Almosnino’s accomplishments, represented by his varied writings, several reprinted a number of times, should make him a person of especial interest. This article will, through his books, describe Almosnino’s multi-faceted scholarship, encompassing rabbinic subjects as well as science, philosophy, history, and rhetoric.

Born in Salonika to a distinguished family from Aragon, his antecedents include Don Abraham Almosnino and Don Abraham Cocumbriel (Cogombriel), both of Huesca, both burned at the stake in Spain on February 1, 1489, by the Inquisition.4 Several members of the family were able to escape including their sons and a daughter, taking up residence in Salonika. Almosnino studied in the yeshiva of R. Joseph Taitazak (c.1465-1487/88-c.1545), a kabbalist and Talmudist of considerable repute considered one of the leading halakhic authorities of his time. Among Almosnino’s instructors in philosophy and science was Aaron Afiya (Afia, 16th century), an ex-converso. The languages he was fluent in include Arabic, Latin, Turkish, and possibly Greek.5

Almosnino served as rabbi of the Sephardic Neveh Shalom community from 1553-1560. Afterwards, from 1560 he was at the Livyat Chen congregation, both in Constantinople. The latter congregation founded by Donna Gracia Nasi.6 Among Almosnino’s offspring are his grandson, R. Joseph ben Isaac Almosnino (1642–1689), born in Salonika, who served as rabbi in Belgrade and was the author of responsa entitled Edut bi-Yhosef (Constantinople, 1711, 1713) published posthumously by his sons Simḥah and Isaac.

A communal leader, Almosnino was among the representatives selected to meet with the Ottoman emperor, Sultan Selim II (1524-1574, reigned from 1566), to confirm a charter of privileges and exemptions previously granted by Suleiman the Magnificent (c.1494/95-1566). Those privileges had been granted in 1537, when Suleiman visited the city. The original document granting those rights was destroyed in a fire in 1545, in which a hundred individuals perished and most synagogues were destroyed together with their libraries and records. Subsequently, local authorities began placing encumbrances on the Jewish community, among them the requirement to provide, annually, at great expense, a herd of goats to the imperial household, this in addition to regular taxation.

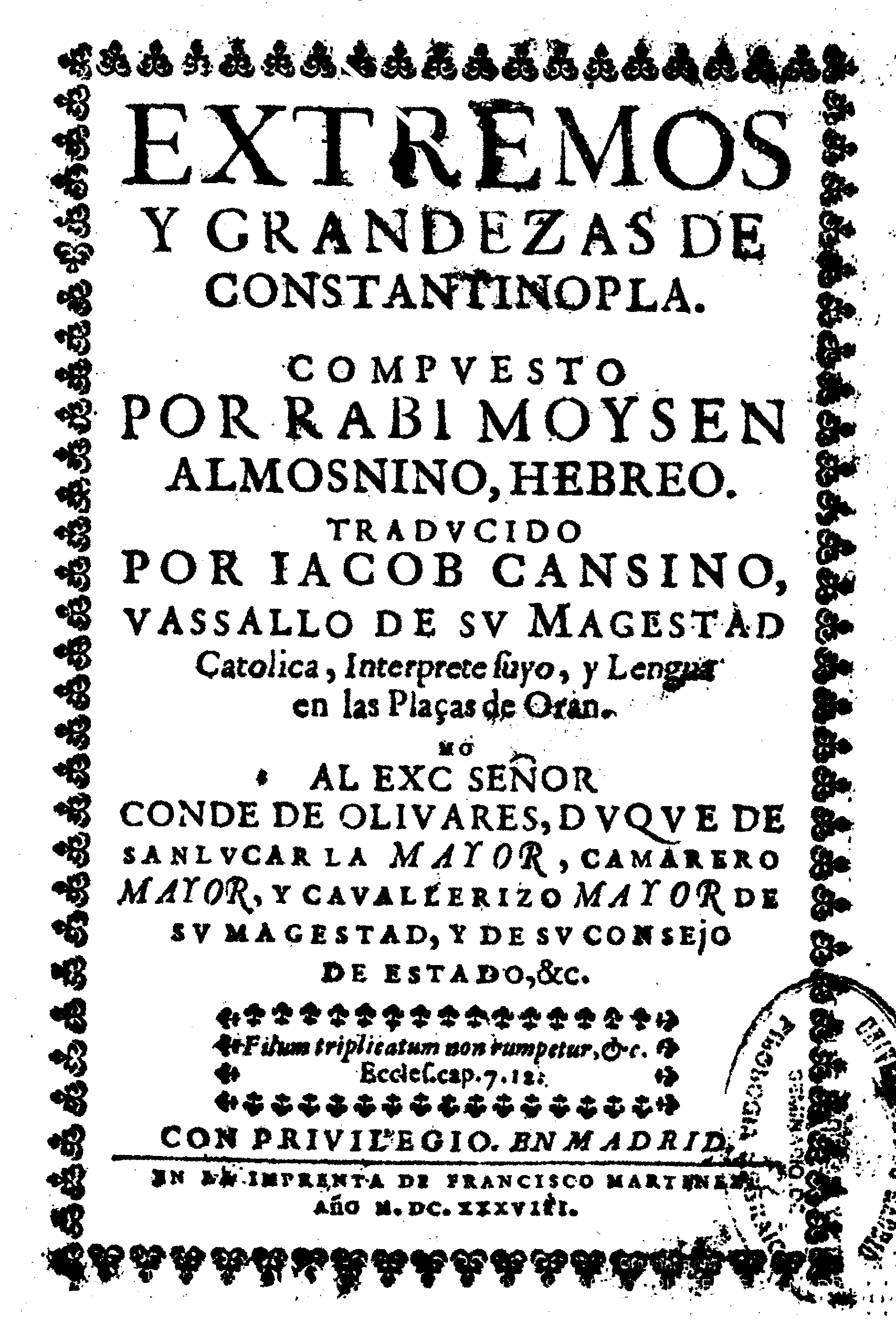

Extremos y Grandezas de Constantinopala, 1638

Courtesy of the Bavarian State Library

In 1565, Almosnino, initially accompanied by two other delegates of repute, Jacob ibn Nahmias and Moses Baruch, both of whom who died on the way, was assisted by Don Joseph Nasi (c. 1524-1579). He succeeded, after great effort, in 1568, in reversing the situation and obtaining the status of a self-governing entity for the Salonika community.7 His efforts are described in The History of the Kings of the Ottomans written in Ladino, “in a unique, and inaccessible, manuscript housed at the Ambrosiana in Milan.” Translated into Spanish as Extremos y Grandezas de Constantinopala (Madrid 1638), it was the first account of the Ottomans in Spanish.8 It was prepared for publication with some editing, by Jacob Cansino (d. 1666), the most prominent member of a prestigious family. Cansino added a preface which includes information about his family’s positions and accomplishments.9

II

We begin with Almosnino’s titles in Ladino. These works are important not only because they reflect his varied interests, indicative of his impressive scholarship, but also because they suggest the intellectual interests of the time. In addition to his own works, Almosnino translated popular Latin works on astronomy into Hebrew, notably Johannes Scarbosco’s (c.1195-c.1256) Tractatus de Sphaera (Ferrara, 1472), which addresses the earth and its place in the universe as Beit Elohim: Perush Kadur ha-Olam. This book was required reading for Western European university students. His translation was accompanied by a commentary, each discussion beginning with the words said by Moses. He also compared Scarbosco’s arguments to those of Aristotle, Ptolemy, and Euclid. Almosnino also translated Georg von Peurbach’s (1423-61) Theoricae Novae Planetarum (New Theories of Planets, 1454) on planetary spheres, as Sha’ar ha-Shamyyim.10

Several of Almosnino’s works were written in Ladino, most notably Libro Regimiento de la Vida (Salonika, 1564) together with Tratado de los Suenyos (Salonika, 1564). In the latter work, Almosnino analyzes the relationship between dreams and philosophy.11

Cecil Roth informs that Tratado de los Suenyos, the latter work, “was composed at the request of the most illustrious Señor Don Joseph Nasi, who may God preserve and augment his prosperous state: Amen!”12 Steven Harvey writes that Almosnino is explicit in his appreciation of Aristotle from the following,

In order to study natural science properly, it does not appear to me that you can avoid reading the physical books of Aristotle. Do not squander your time with the epitomes and middle commentaries of Averroes, but [read] only the long commentaries, for if you read the long commentaries carefully, you will have no need to read any other book in order to understand anything of natural science.13

Based on Aristotle’s Ethics, Libro Regimiento de la Vida (Salonika, 1564) is a homiletic work in which Almosnino attempts to present profound ethical concepts in a clear and simple language. First published in Ladino and republished (Amsterdam, 1729) in Latin letters, it was “Dédié á” (dedicated to) Aharon de David de Pinto.14 Libro Regimento de la Vida is reported to have “enjoyed considerable popularity in its time.”15 Written for Moses Garcon, his sister’s son, it has been described as a “text book on virtuous conduct, on good and evil, on moral responsibility, on the rules of decency, on the conservation of health.”16 Several of Almosnino’s works are extant in manuscript, among them Ladino editions of works later translated and published in Hebrew.17

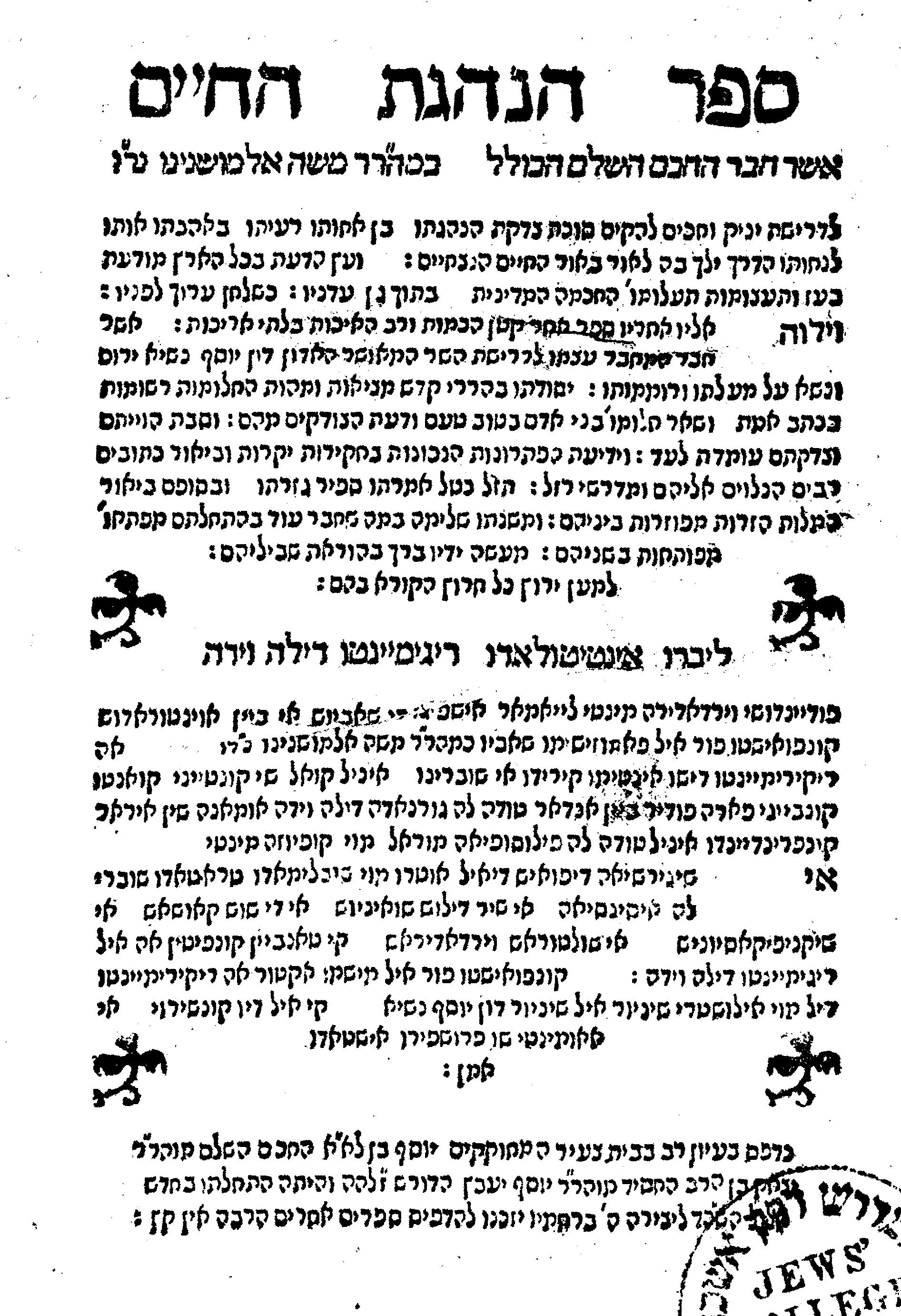

Libro Regimiento de la Vida, 1564

Courtesy of the Israel National Library

Libro Regimiento de la Vida (Hanhagat ha-Hayyim was printed at the press of Joseph Jabez in octavo format (40: 164, 4 ff.). It is a bi-lingual, Ladino-Hebrew work composed by Almosnino, as noted above, for his nephew, with both languages being set in Hebrew letters. The text is in Ladino, excepting the introduction, indices, and chapter heads, which are in Hebrew.

The title page is in two parts, the text in the upper part in Hebrew, repeated below in Ladino, informing that it is,

discourses for the child and the scholar, to set up a tabernacle (סוכה) of righteousness, [correct] conduct [for] the son of his beloved companion [Don Joseph Nasi], to instruct in the way he should go. Furthermore, appended to this work, is a monograph, small in size but of great value, written by the author at the request of the noble Don Joseph Nasi, “Whose foundation is in the holy mountains” (Psalms 87:1) on the actuality and essence of dreams.

The verso of the title page has an introduction in Hebrew, followed by indices, with marginalia, and then the introduction in Ladino (12a). The text is followed, as stated in the introduction, by a five page glossary of difficult Spanish words translated into Hebrew and then errata. Another list of difficult terms translated into Hebrew is appended at the end. Work began in the month of Elul. The only ornamentation on the title page is the customary Jabez florets.

The first part, comprised of fourteen chapters, addresses, as Almosnino explains in the introduction, “in a straightforward manner” ten matters of importance in Torah and Divine service, including food and drink, sleep and awakeness, lying down and rising up, going and sitting, speech and silence. The second part, in twenty chapters, addresses the ten middot (ethical values): might and satisfaction, greatness of heart and humility, generosity and magnanimity, mercy and patience, and civility and truthfulness. The third part, with thirteen chapters, is on righteousness and love, wisdom and knowledge, reason and understanding. Also discussed are the study of secular works, which to be studied, when, and in what order; and human endeavor in this world. The volume concludes with his appendix on dreams. Among the other topics Almosnino discusses in Hanhogot Hayyim are the origin of good and evil, influence of the stars, Providence, the moral life, education of children, and free will.18

Hava Tirosh-Samuelson notes that the Hebrew title, Hanhagat ha-Hayyim (The Book of Management of Life),

indicates how Almosnino understood his educational goal. In his view, moral, intellectual, and religious training, which lead to human well-being, must begin at a young age. The disciplined acquisition of virtues liberates the soul from its corporeal conditioning, restoring it to its heavenly abode. Almosnino's preoccupation with the Ethics was thus an integral part of his moral philosophy, whose goal was to lead Jews to religious perfection. Almosnino's moral philosophy fuses Aristotelian philosophy and kabbalah. His position on the nature of the human soul and the ultimate end of human life reveal the impact on him of the zoharic perspective.19

In addition to reprints in its original form, Hanhogot Hayyim was also reprinted in Latin letters as Libro de la Regimento de la vida in Amsterdam in 1729 by Semvel Mendes de Sola, Joseph Siprut Gabbay, y Jeudah Piza. That edition was dedicated to Aaron David Pinto.20

As noted above, Almosnino was also a kabbalist. Hava Tirosh-Samuelson writes that Almosnino “had to harmonize Jewish Aristotelianism with the views of the Zohar.” He “held that the souls of Jews are literally divine; they are a part of the divine essence, or a ‘particle of God’ (heleq mimenu). Israel’s soul ‘was carved from under the Throne of gory’ (kise ha-kavod) and was ‘infused’ (mushpa’art) into the human body by God.” The soul of Israel is pre-existent, a divine substance, holy, eternal. The Jewish soul is a divine spark; therefore, Israel alone was created in the image of God, so that whenever the Bible uses the word “man” it refers to Israel only, rather than the human species.21

III

We turn now to Almosnino’s Hebrew works. While also not well known today by the general public they are both relatively better known, more recognizable, and more available to the Jewish community, in contrast to his non-Hebrew works. The Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book, an authoritative listing of Hebrew books published from 1469 to 1863, records six Hebrew titles for Almosnino. In order of publication they are: Pirkei Moshe and Tefillah le-Moshe (Salonika, 1563), Hanhogot Hayyim (Libro Regimento de la Vida, (Salonika, 1564), Yedei Moshe (Salonika, 1572), Me'ammez Ko'ah (Constantinople, 1587-88), and Iggeret ha-Halomot (Amsterdam, 1734).22 With some exceptions, most of these books were republished infrequently, if at all. We will address several of these books in some detail, others in passing only.

Pirkei Moshe, Almosnino’s first published Hebrew work, a commentary on Pirkei Avot, has been republished three times, considering modern imprints. Indeed, Stephen Weiss’ Pirke Avot: A Thesaurus: An Annotated bibliography of Printed Hebrew Commentaries records as many as four editions of Pirkei Moshe, beginning with the above noted 1563 edition. The second edition, however, was republished for the first time slightly more than four hundred years later in Jerusalem (1970), followed by Farnborough (1971), and Jerusalem (1995) editions.23

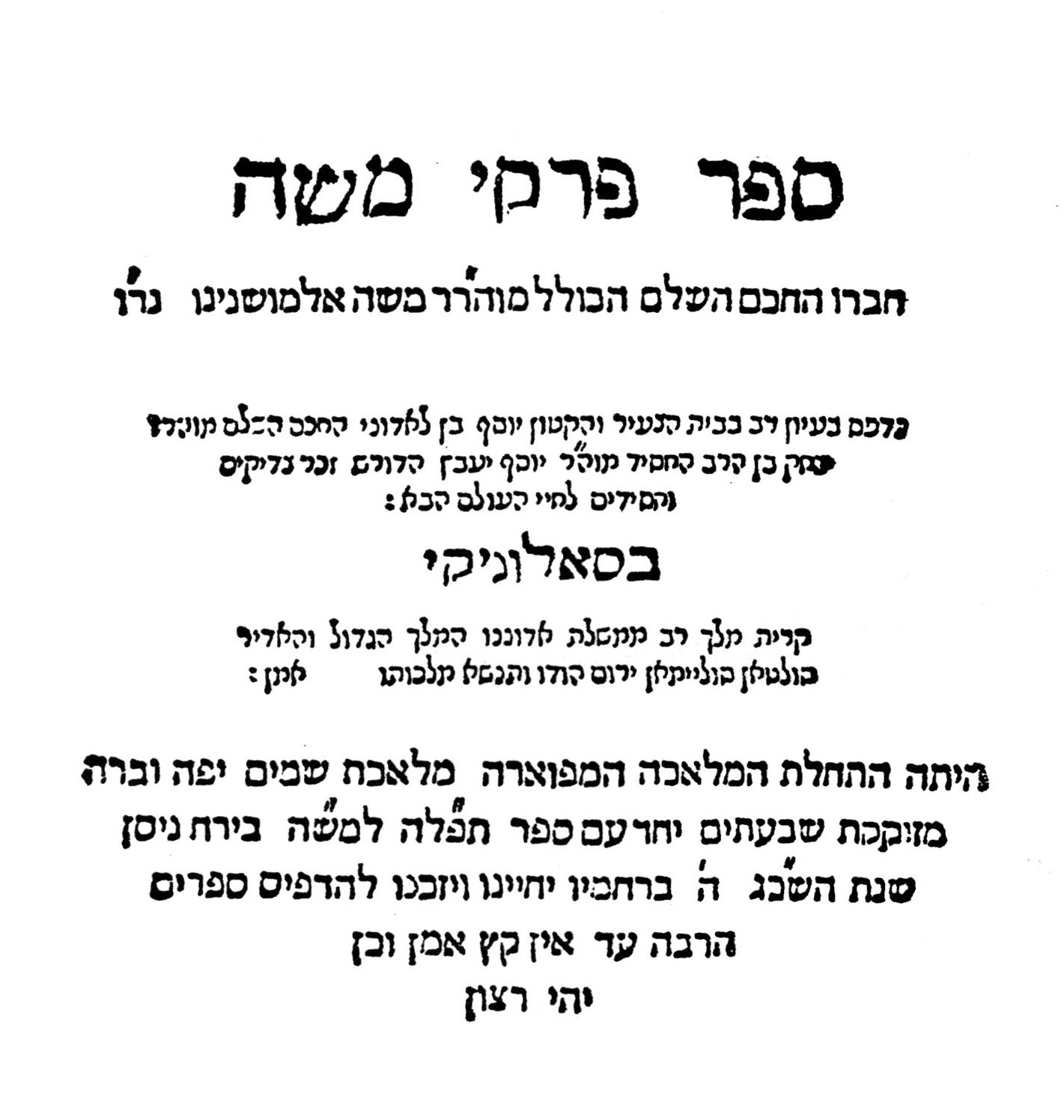

Returning to the Salonika edition of Pirkei Moshe, it was printed in octavo format (80: 111 ff.) by Joseph Jabez in the month of Nissan, שהג (363/1563) together with Tefillah le-Moshe (80: 76 ff.). The Jabez press was founded by Solomon and Joseph ben Isaac, grandsons of R. Joseph Jabez (d. 1507), author of Hasdei Hashem (Constantinople, 1533) in about 1550, and, perchance, according to Ch. B. Friedberg, even as early as 1543. An outbreak of plague (c.1553) forced the brothers to relocate to Adrianople where they printed four books. When the plague abated, Solomon continued on to Constantinople where he established a press. Joseph returned to Salonika where he published the aforementioned books. Joseph continued to print until another outbreak of plague in approximately 1570-72. He then sold his typographical material to David ben Abraham Azubib and left Salonika to join his brother Solomon in Constantinople.24

The title page of Pirkei Moshe, together with Tefillah le-Moshe, informs that printing began in the month of Nissan, 1563. Almosnino completed Pirkei Moshe, according to the introduction to Tefillah le-Moshe, in Elul, in the same year, “[If there are yet many years, according to them] he shall give again (322=1562) ישיב the price of his redemption [out of the money that he was bought for]” (Leviticus 25:51).

The title page is followed by Almosnino’s introduction (2a-2b), and then the text, which concludes on 107a. The text of the Mishnah is in square letters; the lengthy commentary in small rabbinic letters. A table of the contents follows (107b-110a), errata (110a-11b); errata for Mishnayot found in this volume are listed on the last page (111b). There are also infrequent marginalia highlighting verses. Pirkei Moshe was brought to press, as were his other Hebrew works, by Almosnino’s son Simeon. The expense of publication was defrayed by Almosnino’s other sons, Abraham and Absalom.

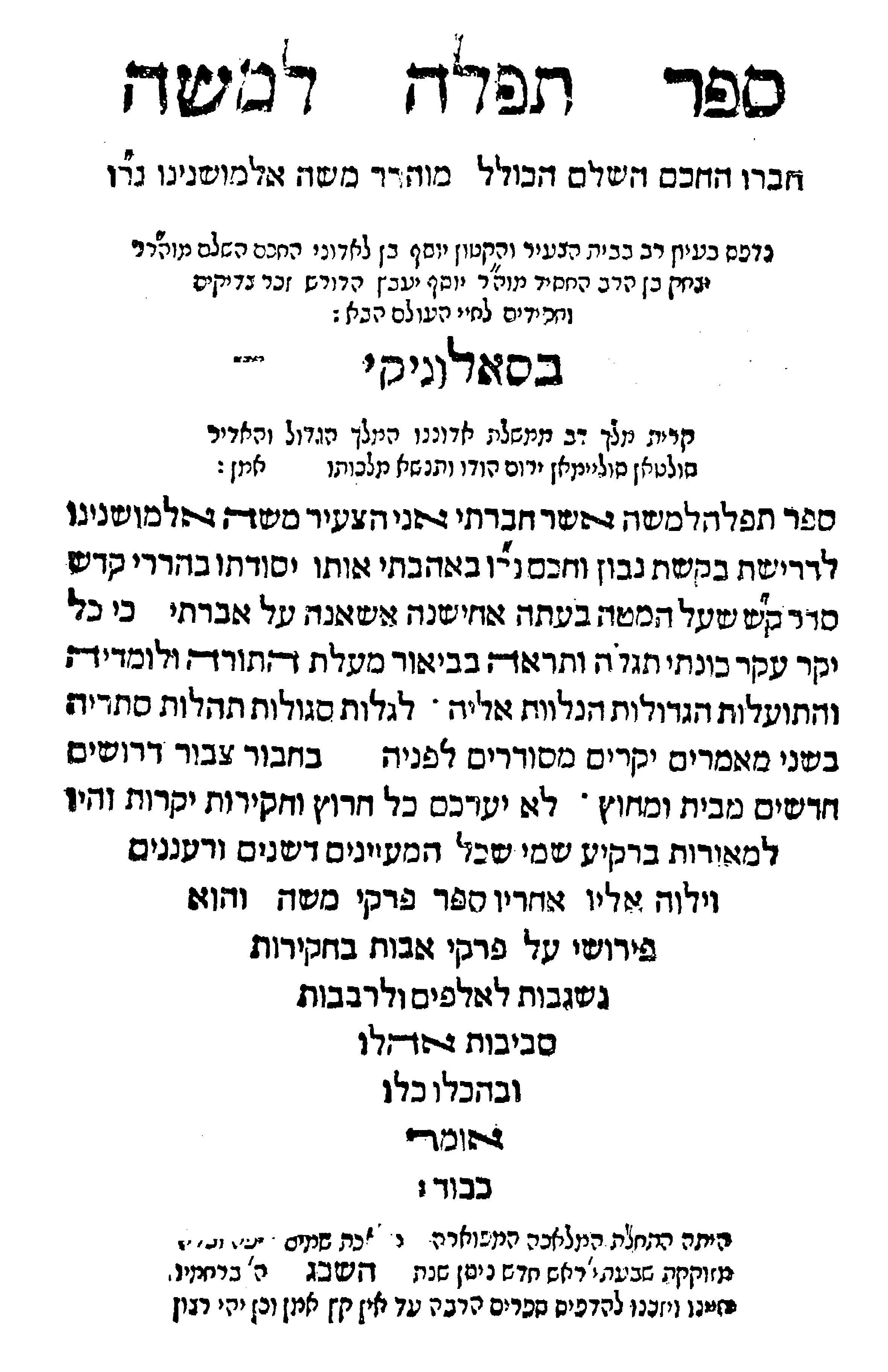

Tefillah le-Moshe, 1563

Courtesy of Hebrewbooks.org

Pirkei Moshe, 1563

Courtesy of Hebrewbooks.org

Tefillah le-Moshe was printed together with Pirkei Moshe, as already noted. Tefillah le-Moshe is on Keri'at Shema al ha-Mittah (prayer before retiring) and the virtue of Torah and its study. Tefillah le-Moshe might be considered Almosnino’s most popular and most successful work; it was republished five times. The Salonika edition was followed by Cracow (1590), Zolkiew (1805), Cracow (1820), Podgorza (1900), and Tyrnau (1903) editions.25 It is insights on the Torah, specifically Keriat Shema al ha-Mitta and the siddur (prayer book). Charles J. Abeles has described it as explaining “the beauty that can be found in the Pentateuch and the later chanters give the significance of the of the Keriat Shema al ha-Mitta.”26

Almosnino’s next titles were Yedei Moshe on the Megillot (1572), also a Jabez publication, in octavo format (80: 246 ff.) and Me'ammez Ko'ah (1582), twenty-eight sermons, mostly funeral elegies. The title-page of Yedei Moshe states that it is a commentary on the five Megillot by the complete sage R. Moses Almosnino. The title-page is followed by a lengthy introduction, and then the text, comprised of the text of the Megillot in vocalized square letters accompanied by Almosnino’s quite extensive commentary in cursive rabbinic letters.

Me'ammez Ko'ah, 1587/88

Courtesy of Hebrewbooks.org

Me'ammez Ko'ah, the last Hebrew title that we will address in any detail, was published twice in the sixteenth century, first in Constantinople by Joseph Jabez in 1582. The Constantinople edition is only extant as a five folio quarto (40) unicum fragment in the Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary.27 Me'ammez Ko'ah was reprinted approximately five years later; in the year, according to the title-page, שמח ‘ה ([5]348/1587/88) at the Venice press of Giovanni di Gara, also as a quarto (40: 236 ff.) by Asher Parenzo. He was a member of the Parenzo family of Hebrew printers and worked for both the Bragadin and the di Gara presses.

The di Gara press, active from 1564 to 1611, is credited with more than two hundred and seventy books, primarily in Hebrew letters. It infrequently published in non-Jewish languages. Giovanni Di Gara, who had apparently worked for Daniel Bomberg, saw himself as a successor to that printer, a fact that he frequently emphasized.28 The di Gara press is noteworthy for the many distinguished fifteenth century scholars associated with it, among them R. Asher Parenzo, R. Samuel Archevolti, R. Israel Zifroni, his son Daniel, R. Leon Modena, and R. Isaac Gershon, and in the following century, R. Israel Zifroni (from 1584), his son Elishema, and R. Judah Aryeh (Leone) Modena. Di Gara’s numerous books with Hebrew letters cover the spectrum of Jewish literature, excepting the Talmud, which was forbidden in Italy in the second half of the sixteenth century. It also included titles in Yiddish and Ladino. Many of di Gara’s imprints have three crowns on the title-page, a press-mark associated with the Bragadin press.

The title of Me'ammez Ko'ah comes from the verse “[A wise man is strong; and a man of knowledge] increases strength” (Proverbs 24:5). On the verso of the title page is a preface from Asher Parenzo, the firm’s Hebrew printer, who remarks that in this small book of great value the author of Me'ammez Ko'ah (כח = 28) of twenty-eight discourses, “He has declared to his people the power כח of his works” (Psalms 111:6) and that the book was brought to press by Almosnino’s son Simeon. Simeon’s introduction (2b) begins by noting his great pain at the loss of his parents and how, with the financial aid of his brothers, he is printing his father’s books. This is followed by Moses Almosnino’s introduction (right), the text, an index (226a-235a), and then (235b-236) an epilogue from Simeon.

Me'ammez Ko'ah, 1587, front-piece

Courtesy of Hebrewbooks.org

In the epilogue, Simeon again declares his intent to print his father’s other works and remarks that because the non-Jewish staff worked daily, particularly erev Shabbat when the book could not be checked for errors.29 Last are the concluding words from the printer, and the almost formulaic apology for any possible errors, for, “Who can discern mistakes” (Psalms 19:13). Below the apologia is a variation of the pressmark of Joseph Shalit, here an ostrich (peacock) standing on three rocks, facing left, with a fish in its beak within a cartouche, above it the verse, “The wings of the ostrich wave proudly,” (Job 39:13) and on the remaining three sides, “My soul is consumed with longing [for your judgments at all times]” (Psalms 119:20).30

Me'ammez Ko'ah, 1587, tail-piece

Courtesy of Hebrewbooks.org

In contrast to the title-page of Me'ammez Ko'ah, which is dated in a straightforward manner, the colophon informs that work began on Rosh Hodesh Heshvan in the year, “Who is wealthy, he who is happy השמח (5348/Monday, November 2, 1587) with his lot” (Avot 4:1). It was completed on “The hand [ב]יד is on the throne of God” (Exodus 17:16) in the month, “[That the sons of God saw the daughters of men] that they were good טבת (14 Tevet [5348] /Thursday, January 14, 1588)” (Genesis 6:2).

This edition of Me'ammez Ko'ah is the first of Almosnino’s books printed posthumously. Each discourse begins with the number of the discourse in large square letters, when and where it was delivered in small rabbinic letters, the subject matter in square letters, and then the discourse in rabbinic letters. The discourses cover a variety of subjects, for example, one was delivered upon his return from Constantinople, when he represented the Jews of Salonika before the Sultan (as noted above, 1563), several eulogies, among them one for the dayyan R. Joshua Soncin (d, 1569), perhaps, a son of the famed printer Gershom Soncino. Almosnino also frequently refers to his other works in this book, as in his other titles.31

Several other works, either by Almosnino need be noted. Perushim le-Rashi is listed at the National Library of Israel.32 In addition to Almosnino two others are recorded as co-authors, that is [R. Jacob] Kanizel and R, Aharon Albilda. The title-page provides no publication information, but the NLI lists it as a 1525 imprint. It is, in format, a quarto (40: 98; 73 should say 75 ff.) and gives the place of printing as possibly Constantinople.33 Another Ladino work is Iggeret ha-Halomot It is described, concisely, by Isaac Benjacob, as being on dreams in Sephardit (Ladino), adding “(see Hanhagat ha-Hayyim).”34 This work was prepared at the behest of Don Joseph Nasi.35

Still in manuscript are Ner Moshe on the Torah and a commentary on Job. Almosnino’s responsa were never printed as a separate work. Many other decisors, however, such as Samuel de Medina, Hayyim Benveniste, Isaac Adarbi, and Jacob di Boton included Almosnino’s responsa in their own collections of replies to inquiries. Still in manuscript is Sha'ar ha-Shamayim, a Hebrew translation of Prubach's Theory of the Stars, and Migdal Otz, a commentary on Abu Achmed Algazali's Kavnot ha-Filosofim.36

IV

We began by noting that Almosnino “is among the foremost sages of Salonika in the sixteenth century. A multi-faceted eclectic scholar, well known in his time and highly regarded in rabbinic and academic circles today, he is barely remembered today by the general population.” After writing this article, that opening line requires some modification. The wide variety of sources referenced in this article, and there are others that were not quoted, certainly confirms that he is well-known and highly regarded in contemporary rabbinic and academic circles. However, whether he is remembered by the general population remains open to question. Perchance, he is better known than originally suggested but it still appears that Almosnino is not widely known, not a household name.

This is unfortunate, for his accomplishments are certainly significant. A prolific author, his works encompass several languages and include original titles on a variety of subjects, scientific, philosophical, and homiletic, some with kabbalistic content. They were written in both Ladino and Hebrew as well as translations of treatises from Latin into Hebrew. In addition to these scholarly activities, Almosnino was also a communal leader, representing the Jewish community of Constantinople on a difficult mission to Sultan Selim II.

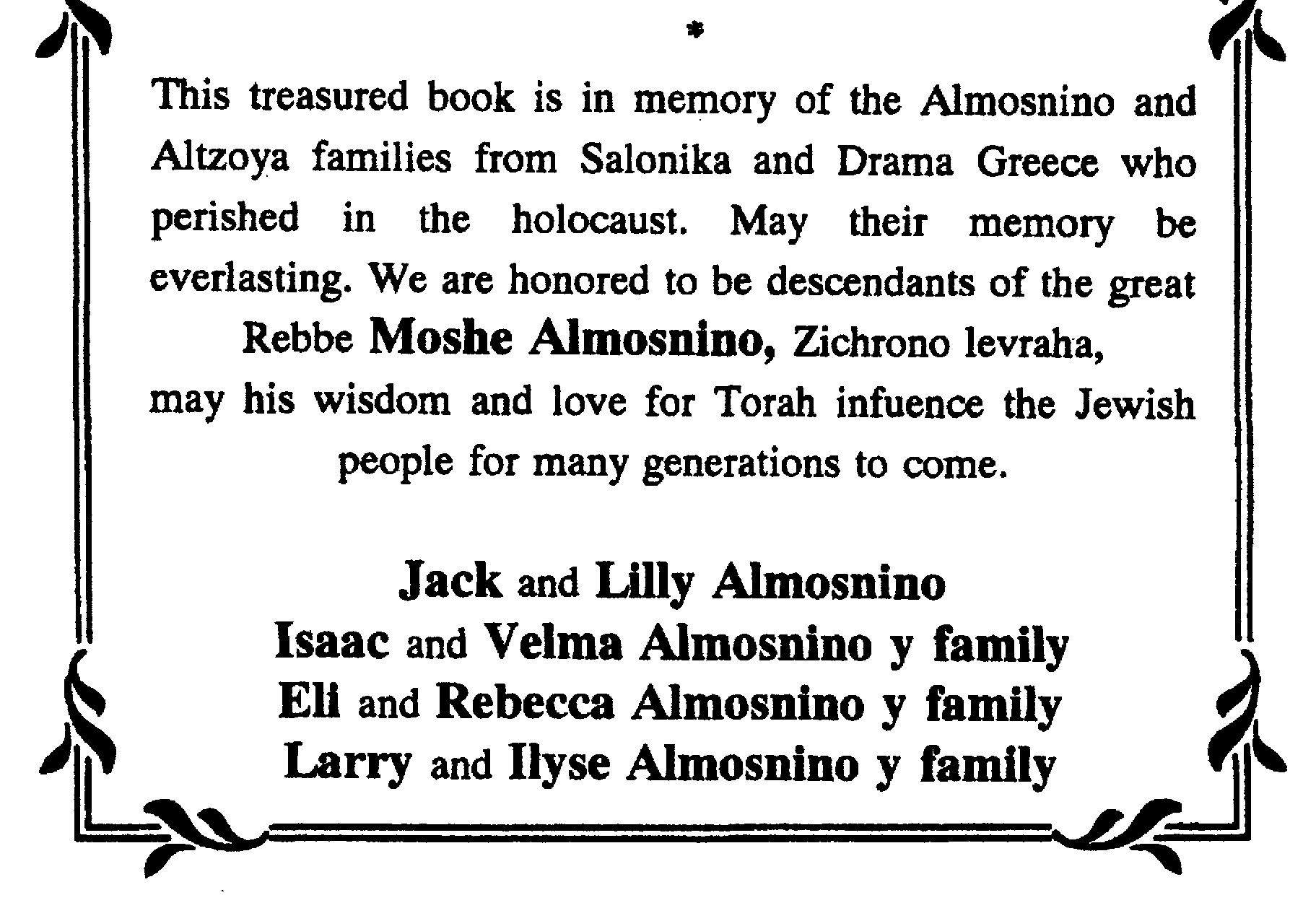

Almosnino family dedication

His descendants have remained active in Jewish affairs. The Almosnino family is credited with the publication of the 1995 Jerusalem edition of Pirkei Moshe. That edition has a bi-lingual Hebrew and English dedication page. We conclude with latter English text, which honors the families who perished in the holocaust and R. Moses Almosnino.

1 Once again, I would like to express my appreciation to Eli Genauer for reading the article and for his editorial corrections.

2 Marvin J. Heller is an award winning author of books and articles on early Hebrew printing and bibliography. Among his books are the Printing the Talmud series, The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Hebrew Book(s): An Abridged Thesaurus, and several collections of articles.

3 Examples of these little-known academic works can be seen from the books and articles referenced in this article, several unknown to this writer before he began working on the article.

4 Mordechai Margalioth, ed. Encyclopedia of Great Men in Israel IV (Tel Aviv, 1986), cols.1077-79 [Hebrew]; Don Abraham (d. April 1, 1489) belonged to the Jewish community of Huesca. He assisted Juan de Ciudad, a converso, to return to Judaism in 1465. Twenty years later Don Abraham was condemned by the Inquisition for his participation in this and subsequently burned alive for it on December 10, 1489. His two sons, Hayyim and Joseph, and daughter, married to Don Abraham Cocumbriel fled to Salonika (Cecil Roth, “Almosnino," Encyclopedia Judaica, 1, pp. 684-685; Shimon Vanunu, Encyclopedia Arzei ha-Levanon. Encyclopedia le-Toldot Geonei ve-Hakhmei Yahadut Sefarad ve-ha-Mizrah I (Jerusalem, 2006), pp. 30-31 [Hebrew].

5 Hava Tirosh-Samuelson, “Religious Perfection and the Interplay of Philosophy and Kabbalah,” in Happiness in Premodern Judaism: Virtue, Knowledge, and Well-Being (Cincinnati, 2003), p. 429.

6 Hersh Goldwurm, ed. The Early Acharonim (Brooklyn, 1989), p. 92. Concerning Donna Gracia Nasi see Marvin J. Heller “Belvedere and Kuru Tsheshme: A Brief but Valuable Intervals in Hebrew Printing (Sephardic Horizons, 2019), vol, 9 nos. 1-2; reprinted in Essays on the Making of the Early Hebrew Book (forthcoming).

7 Abraham Hirsch Rabinowitz, “Moses ben Baruch Almosnino: A Sixteenth Century Multi-Faceted Sephardic Sage in Salonika,” Encyclopaedia Judaica, I, p. 685. Cecil Roth, The House of Nasi: the Duke of Naxos (Philadelphia, 1948), pp. 1765-66.

8 Avner Ben-Zaken, “Bridging Networks of Trust: Practicing Astronomy in Late Sixteenth-Century Salonika To the memory of Richard Popkin,” 23:4 (Jewish History, 2009), p. 356.

9 David Corcos, “Cansino,” EJ 4, p. 432; Meyer Kayserling, Biblioteca Espanola-Portugueza-Judaica (1890, reprint with Prolegomen by Y. H. Yerushalmi, New York, 1971), p. 33.

10 Ben-Zaken, p. 350.

11 Jonathan Karp, Adam Sutcliffe, Editors, The Cambridge History of Judaism: The Early Modern World, 1500-1815 VII (Cambridge, 2019), p. 262.

12 Roth, The House of Nasi, p. 170.

13 Steven Harvey, “The Hebrew Translation of Averroes' Prooemium to His "Long Commentary on Aristotle's Physics,” Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research, 52 (1985), p. 61, referencing Moses Almosnino, Regimiento de la vida in Simhah Assaf, Meqorot le-Toledot ha-Hinnukh be-Yisra'el (4 vols.; Tel-Aviv: Dvir Co. Ltd., 1930-1954), vol. III, p. 13.

14 Kayserling, p. 33.

15 Rabinowitz.

16 Charles J. Abeles, Moses Almosini, his Ethical and other Writings "A Study of the Life end Works of a Prominent, Sixteenth Century, Salonikan Rabbi. Doctoral Dissertation ( 1956-57), p. 29. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/237601712.pdf.

17 For a listing (partial) of manuscript editions of Almosnino’s titles see Jose Maria de Agustin Ladron de Guevara y Maria Luisa Salvador Barahoma, Ensayo de un Catalogo Bio-bibliografico de Escritores Judeo-Espańoles-Portugueses del Siglo X AL XIX (Madrid, 1983), pp.73-74.

18 Marvin J. Heller, The Sixteenth Century Hebrew Book: An Abridged Thesaurus II (Leiden, 2004), pp.548-49.

19 Steven Harvey, “The Hebrew Translation of Averroes' Prooemium to His "Long Commentary on Aristotle's Physics,” Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research, 52 (1985, p. 61, referencing Moses Almosnino, Regimiento de la vida in Simhah Assaf, Meqorot le-Toledot ha-Hinnukh be-Yisra'el (4 vols.; Tel-Aviv: Dvir Co. Ltd., 1930-1954), vol. III, p. 13.

20 Avraham Yaari, Catalogue of Judaeo-Spanish Books in the Jewish National and University Library, Jerusalem Supplement to Kirjath Sefer X (Jerusalem, 1934), p. 29 n. 198 [Hebrew].

21 Tirosh-Samuelson, pp. 426-27.

22 Yeshayahu Vinograd, Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book. Listing of Books Printed in Hebrew Letters Since the Beginning of Printing circa 1469 through 1863 I.(Jerusalem, 1993–95), p. 196 [Hebrew].

23 Steven J. Weiss, Pirke Avot: A Thesaurus: An Annotated bibliography of Printed Hebrew Commentaries, 1485 - 2015 [Hebrew with English introduction], pp. 28, 225, 226, 299.

24 Ch. B. Friedberg, History of Hebrew Typography in Italy, Spain‑Portugal and the Turkey, from its beginning and formation about the year 1470 (Tel Aviv, 1956), pp. 134, 144 [Hebrew]. Concerning Hebrew printing in Adrianople see Marvin J. Heller, “In a Time of Plague: Hebrew printing in Adrianople” Los Muestros, (Brussels, 2010), part 1 no. 80 pp. 19-22; part 2 no. 81, pp. 17-19, reprinted in Further Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book, (Leiden/Boston, 2013), pp. 79-90.

25 Ch. B. Friedberg, Bet Eked Sepharim, (Israel, n.d.), tav 1663.

26 Abeles, pp. 41-42.

27 Avraham Yaari, Hebrew Printing at Constantinople (Jerusalem, 1967), pp 130, no. 201 [Hebrew].

28 A. M. Habermann, Giovanni Di Gara: Printer, Venice 1564-1610. ed. Y. Yudlov (Jerusalem, 1982), pp. ix-xvi [Hebrew].

29 Concerning the problem of Shabbat work by non-Jews see Marvin J. Heller “And the Work, the Work of Heaven, was Performed on Shabbat,” The Torah u-Maddah Journal 11 (New York, 2002-03), pp. 174-85, reprinted in Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book (Leiden/Boston, 2008), pp. 266-77.

30 Avraham Yaari, Hebrew Printers’ Marks, (Jerusalem, 1943), pp. 12, 132 no. 19 [Hebrew].

31 A. M. Habermann, Giovanni Di Gara: p. 50 no. 102; Heller, Sixteenth Century, II pp. 744-45.

32 It is reproduced on Hebrewbooks.org.

33 National Library of Israel, system number 990012026700205171.

34 Isaac Benjacob, Ozar ha-Sefarim (Vilna, 1880), p. 10 no. 208 [Hebrew].

35 Pirkei Moshe, (Jerusalem, 1995), p. 3 [Hebrew].

36 Giovanni Bernardo de Rossi, Dictionary of Hebrew Authors (Dizionario Storico degli Autori Ebrei e delle Loro Opere), with a Prolegomen by Marvin J. Heller (Lewiston, 1999), p. 33.