Muslims Listen in the Synagogue: An Intercommunal Reading of the Ten

Commandments on Shavuot

By

Hagar Salamon and Harvey E. Goldberg1

Interpreting the complex relationship between Jews and Muslims in Muslim lands has been discussed elsewhere with reference to basic religious and cultural orientations, law and policy, local interests, and even the impact of interpersonal relationships.2 Together these factors yield a dynamic picture that varies over time and space. An important source of input to this picture has been ethno-historical research on Jewish communities recently uprooted from their original settings that has focused upon everyday practice in concrete contexts, and on the cultural conceptions arising from them.3 From the distance spanning a single life, and the shift to an entirely different quotidian existence, ethnographic enquiry turns back to former praxis and seeks, together with the people who experienced that reality directly, to approach the underlying conceptions that informed it. This enterprise has revealed nodes of interaction and expression laden with significance that illuminate aspects of the simultaneous closeness and distancing that linked and separated members of both religions who once shared the same life-space.

The research discussed herein focuses on a single ethnographic spectacle for which we seek to supply both context and interpretation. An interview with a former resident of Gafsa in southwestern Tunisia, now living in Israel, presented us with an ethnographic surprise.4 While speaking about the ritual reading of the Torah on Shavuot, he recalled that Muslim notables would come to the synagogue to listen to a translation-explanation, a tirgum, of the Ten Commandments into Arabic, which had become part of the local liturgy. This was a surprise to us. We later found it mentioned very briefly in two accounts of customs in rural Tripolitania,5 but our interlocutor mentioned it in a matter-of-fact manner: as an integral component of the web of interaction between Jews and Muslims in his town. He then described how some Muslim notables would be sure to come to the synagogue on the two days of Shavuot to listen to the Ten Commandments, the first five of which were read on the first day of the festival and following five on the second day. In his eyes, this practice was a clear indication of the importance that the Muslims attached to the Ten Commandments, and consequently to the deep belief they held in the “correctness of the Torah” and its laws.6 This initial interview was for us the beginning of an ethnographic exploration of a series of questions regarding the very existence of the practice in a number of communities, the ways in which it was carried out, and the web of meanings arising from it.

As is known, the Torah reading for Shavuot is the Ten Commandments taken from Exodus, Chapter 20. Because of the centrality of this portion, it has become customary since antiquity to embellish the synagogue liturgy with piyyutim that elaborate its content and meaning. This practice, once featuring compositions in Aramaic, was later transposed into Judeo-Arabic.7 An example, existing in several versions in the Maghreb, has been labeled by Joshua Blau Tafsir el-`ashar al-kalamat, a Rhetorical Paraphrase of the Ten Commandments.8 We note that among the other historic forms of poetic embellishment, this translation-explanation into Arabic makes the liturgical text accessible to non-Jews.

With this background, we envision the scene of entering into a synagogue on the afternoon of the two days of Shavuot, guided by our interviewee's descriptions. One can sense a special atmosphere among those present, only males, garbed in white. Muslim notables appear, also dressed in white. They sit down among the congregation, on a bench, that is built against the wall and padded with a mat. In the center of the room is a raised platform, the bima, upon which stands a lectern the teva, surrounding by chanters, the payyetanim. The Commandments are first read in Hebrew, sometimes followed by an Aramaic targum, and then a translation-explanation is chanted in Arabic in a linguistic register described as more formal and “higher” by our interlocutors. All these features were described to us as bearing special significance to the Muslim guests who were received on this unusual occasion within the synagogue.

Our approach is to view this event through an ethnographic lens and to suggest interpretations relating to the complex weave of relationships linking Muslims and Jews in different communities along with religious meanings arising from such unusual ritual collaboration. We begin by noting that, its unique character notwithstanding, this was not the only occasion in which ritual mutuality linking Jews and Muslims existed in North Africa.9 We open a window on this perspective by citing Tripoli-born Mordecai HaCohen who, early in the twentieth century, depicted Jews living among Berber and Arab Muslims in Jebel Nefusa in Tripolitania.10 He distinguished between Muslim behavior toward Jews based upon what he saw as religious principles of Islam and behavior in the tribal areas where competition between rival leaders highlighted a behavioral code based on “honor.”11 In the absence of a strong central government, tribal leaders were called upon to demonstrate their strength of will by protecting everything and everyone within their realm, including Jews dependent on this protection.

With reference to our current study, one might say even more. Within the social-cultural “whole,” along with the Jews playing central economic functions as also described by HaCohen,12 Jews were an integral part of the value and even the religious system. In these cases, members of one group appear in the rituals of the other and shared some basic conceptions.

Without going into details, one may view the importance that Muslims attached to Jewish rituals in a comparative framework by referring to the work of Victor Turner and the concept of “the power of the weak.”13 His studies of “the ritual process” in other areas provide examples of how socially weak groups are seen as linked to hidden forces that affect all the groups within a region such as rain and the power of procreation, that affect humanity at large.

We thus reach the working assumption that a widespread web of ritual forms and assumptions shared by Muslims and Jews existed at the same time that such mutuality did not entail equality between the parts making up the whole. On this basis we turn to the present research.

A major challenge to our project, which sought to bridge time and distance in gathering data, was to find the appropriate interviewees; the phenomenon of Muslims visiting the synagogue on Shavuot appeared only in some communities in the regions of our concern. We soon discovered that straightforward principles of geographic proximity or the existence of national borders did not provide a simple key. Eventually, we discovered people who could describe instances of such visits, who came from towns in south-central Tunisia and scattered communities in Tripolitania, the hinterland of Tripoli.

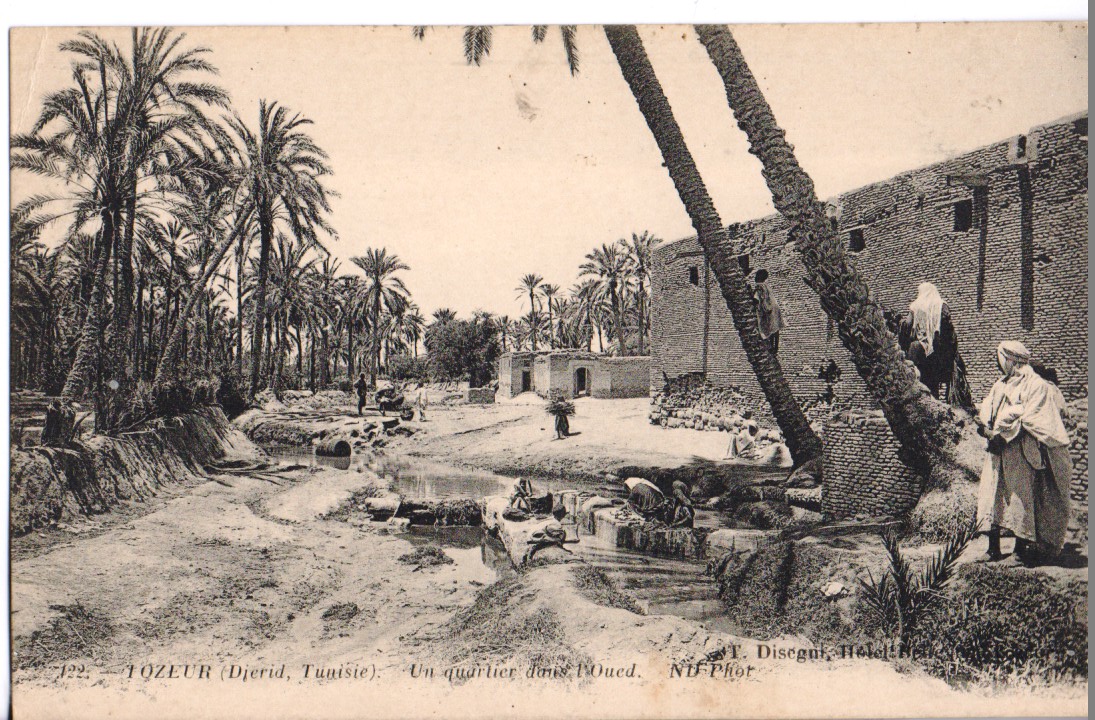

A quarter in Tozeur adjacent to the wadi, Djerid region adjacent to Gafsa, Tunisia.

Courtesy of Tzivia and Yosef Tobi.

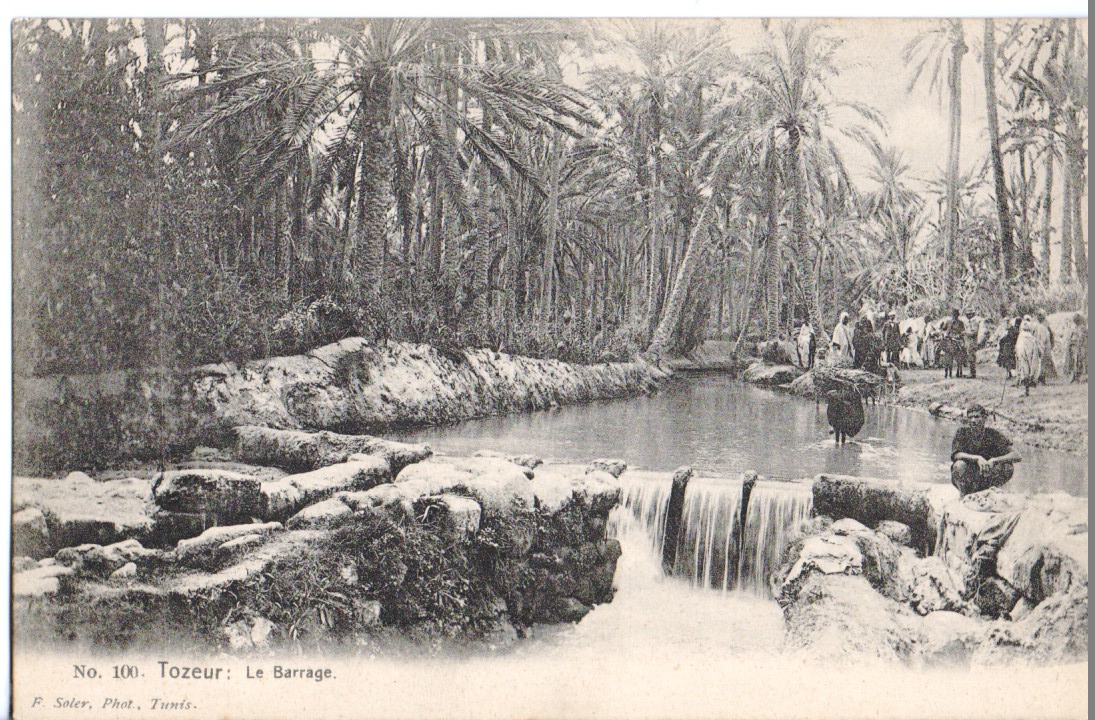

Tozeur: Le Barrage, The Dam.

Courtesy of Tzivia and Yosef Tobi.

Our research mainly reflects in-depth interviews carried out with these people, the Jewish participants, to which we add analysis and interpretation. Some of our findings, in particular the descriptions of how the ritual event was carried out, show striking uniformity which leads us to feel that we are on firm ground regarding the basic facts. We also found consistency in the meanings attached to the events by our Jewish interlocutors, whether by virtue of connections appearing in their responses, or by explanations they appended to their descriptions. But as we seek to expand our view to include the Muslim participants we are pushed to look for hints in additional directions, whether these appear explicitly in the interviews or seem to lurk beneath the surface. When interviewees utilize highly specific expressions, describe spontaneous reactions, or implicitly convey structured associations between different topics, we assume that we are on a path leading to the interpretation of basic cultural conceptions that are not always explicit or conscious.

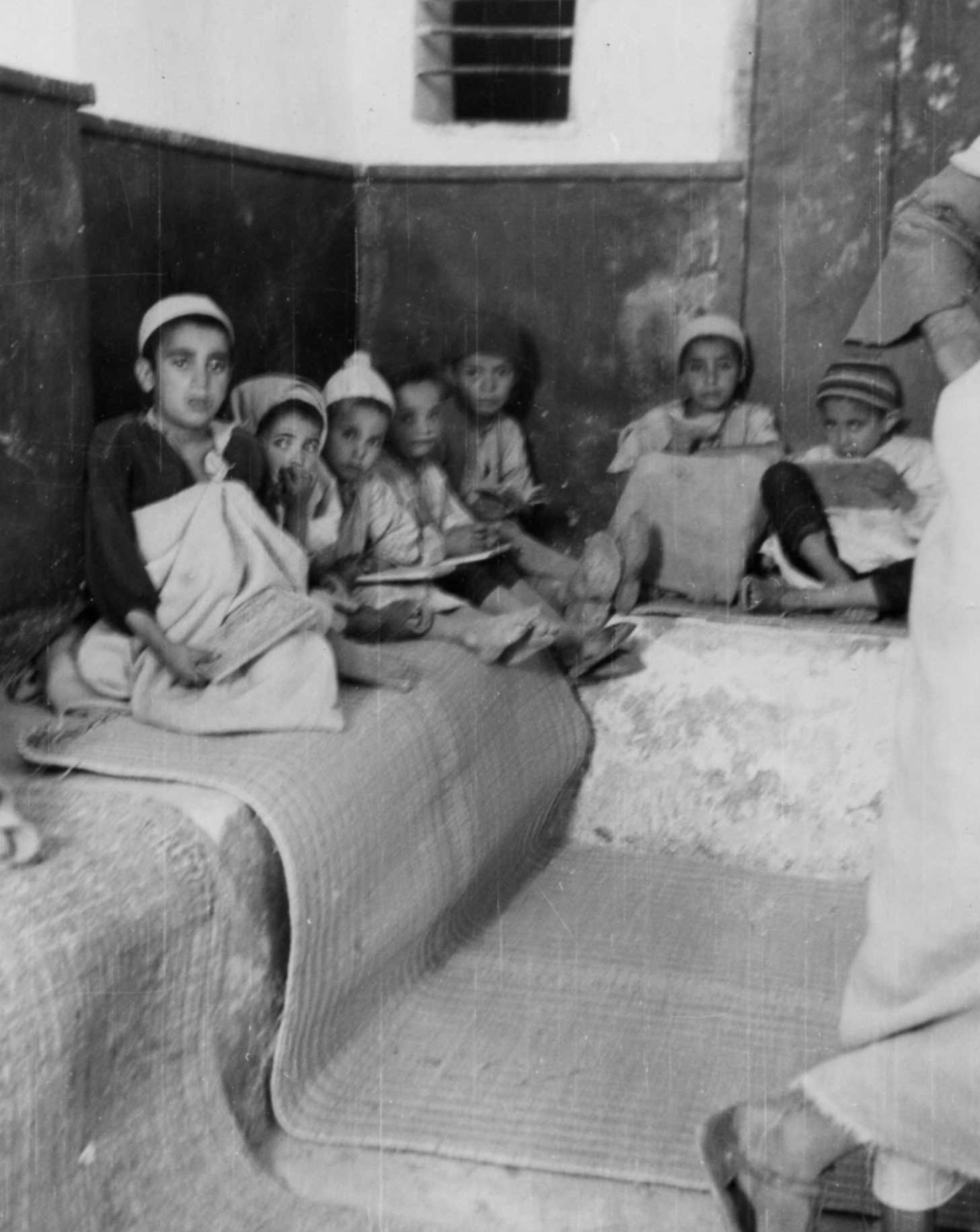

Interior of synagogue in the Gharian plateau, Tripolitania. Courtesy of Amos Gordon Collection, World Organization of Libyan Jewry.

Interior of synagogue in the Gharian plateau, Tripolitania. Courtesy of Amos Gordon Collection, World Organization of Libyan Jewry.Each interviewee described Muslims who came to the synagogue to listen to the Ten Commandments in terms of their own specific town or village. They gave detailed accounts of the guests, who were received with respect and honor, listening to the reading attentively. An example is the description of Eliahu, a native of Gafsa:

“[They came to the synagogue] only on Shavuot. We did Shavuot two days14 and read the [Ten] Commandments. Then all the Sheikhs and Notables of the Arabs come to the synagogue. They like to hear the Commandments in Arabic, because it is their language…Today, five out of the Ten Words,15 and tomorrow the same thing: the second five. So the Arab notables came…the most Honorable came…and sat in the synagogue and listened…and the Jews would explain to them in Arabic. [They sat] in the center together with us…in the most honored places. And the Jews, the first payyetan (chanter), would recite the first section: the First Commandment. Then another would come and recite the Second [Word]. They came to hear the Ten Commandments. They know that the Commandments are something good. Not ‘just anything.’”

We next quote from the account of Aharon from Disr, a hamlet in Jebel Nefusa in western Tripolitania:

“It took place in our [village]. My father was the rabbi of two villages, and served in the ancient synagogue. So the Arabs came: the Qadi, the Mudir, the Sheikh, three or four came16… They were dressed all in white, both their trousers and shirt, and sat near the teva and listened to the Commandments. My father would recite and two or three [payyetanim] were next to him. He recited once, and then a second and third time: also in Aramaic and also in the Arabic that they understood,17 and it was good. I was a child and also sat near the big teva. My father would stand and recite and the congregation was lower down, surrounding him. There were no chairs, but a cement "step" [against the wall], and they sat there rather than on the floor and listened to all of the Ten Commandments. When they finished they got up and said ‘mabruk ‘id el-yahud, Hag Sameah on your holiday, Jews.’”

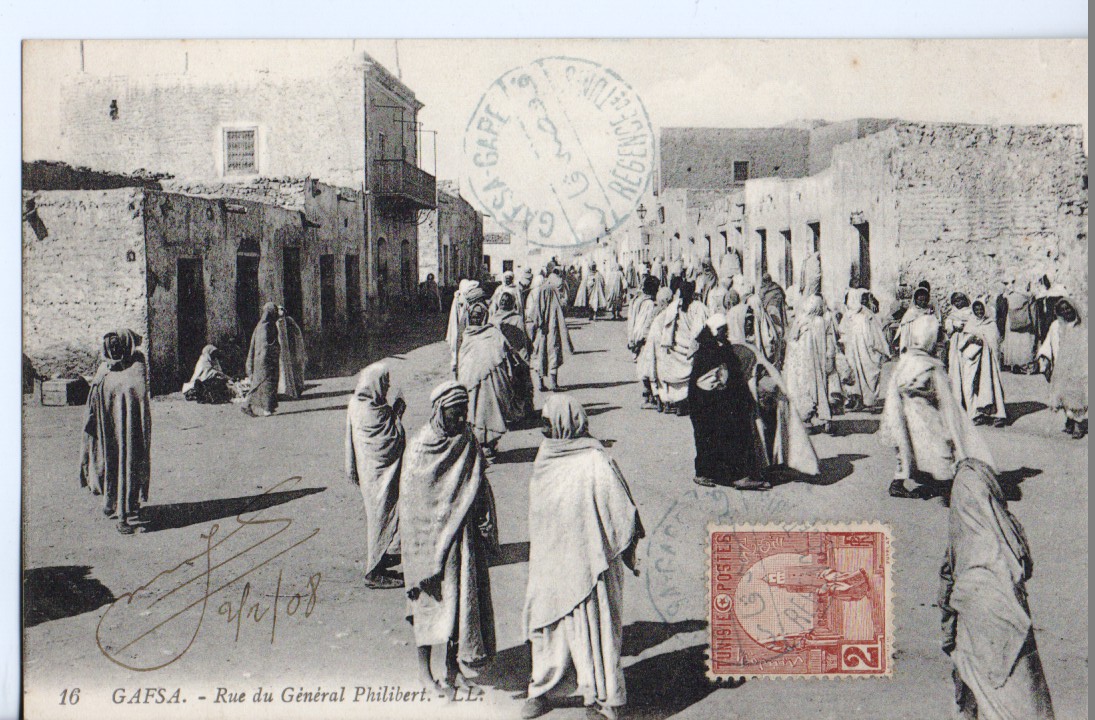

Rue du General Philibert in Gafsa .

Courtesy of Tzivia and Yosef Tobi.

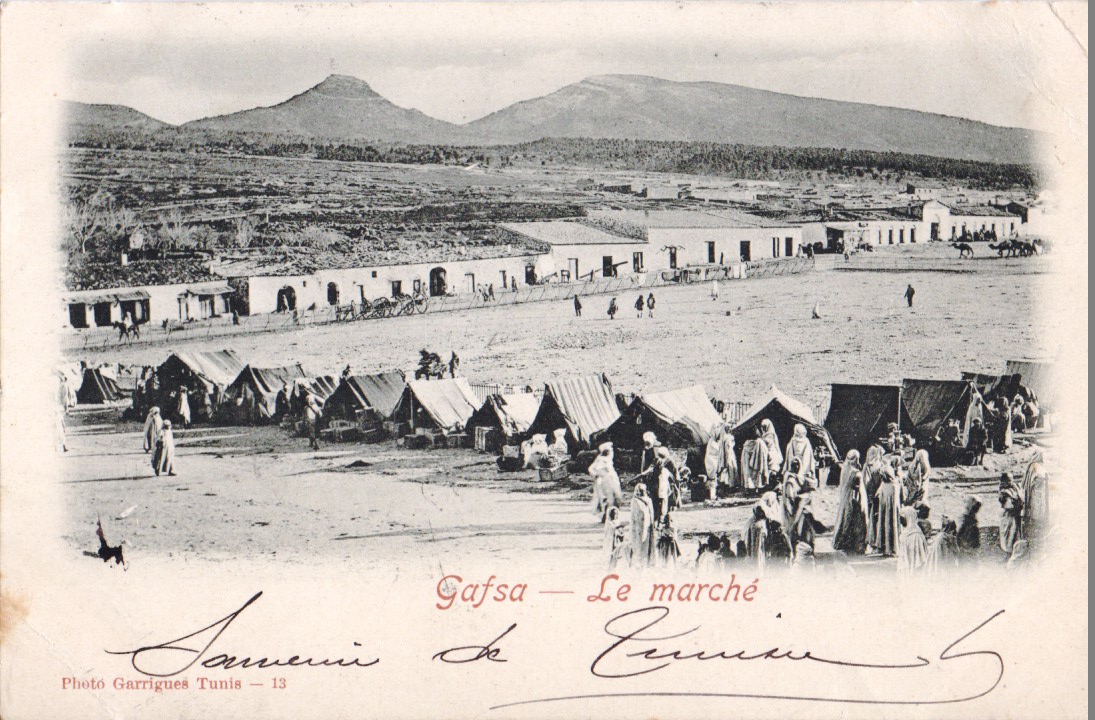

The market in Gafsa, Southwestern Tunisia.

Courtesy of Tzivia and Yosef Tobi.

Moshe, from Misurata, a coastal town in eastern Tripolitania, provided the following recollection:

“On Shavuot…those with a pleasant voice would recite the Commandments. The pleasant voice, the melodies, and the words aroused emotions and brought tears to the eyes. It was all about morality and the Words of God, and for the Arabs that was the main point. When they heard these words it pleased them and that is why they came.”

With these initial accounts in mind, we turn to several interrelated lines of analysis that also will include more details of the mutual ritual events.

The descriptions of Muslims’ participation in the public reading of the Commandments repeatedly emphasized the aspect of listening. In some cases this was highlighted by referring to the Muslims who asked Jews to be quiet and not disturb. Thus, their attendance at the event was not just to “make an appearance,” but stemmed from a desire to relate to the content of the reading, and perhaps also to “re-experience” the founding religious event. Some interviewees remembered Muslims crying as they listened to the reading. We recall here the claim that the Arabic was in a high literary register, and that the melody was moving.18

In discussing the links and the boundaries between Judaism and Islam, attention should thus be directed toward the interlaced channels of listening, speaking, and reading. These topics are discussed in an overview by Daniella Talmon-Heller who points to the importance of precise correct reading in both religions as well as to the ability of a powerful recital to lead to trembling and even tears.19 At the same time, transmission through recital in Judaism is inextricably linked to the presence of a physical text that the eyes of both the reader and the listener should follow, while in Islam, oral transmission including memorization of the Quran and its aural emotion-laden reception, are the main channel linking the believer to his faith. This aspect of Muslim habitus appeared in our interviews through depictions like: “they listened without moving,” or “they actually said ‘it made me shiver’,” or simply “they would cry.”

What, regarding the Muslims, might we possibly infer from these testimonies? While, from one perspective, the depictions of our Jewish interlocutors appear to resonate with shared religious sensibilities, our evaluation is that the palpable religious experiences of the visiting participants should not be separated from their own beliefs as Muslims. One might even suggest that, as highly respected individuals in the region, their desire to be close to a foundational religious moment by listening to the Arabic rendition of the Commandments deepens their faith as Muslims.

This hypothesis is based, obviously, on a view from a distance. It stems, in our view, from forms of expression and cultural notions pointing to an underlying “cultural DNA” that informs both how the ritual event is grasped, and the relations between Muslims and Jews in this context. But from the point of view of the Jewish interviewees who explicitly offered their descriptions, such an interpretation is less satisfactory. When we asked about the meaning of the strong emotional responses of the Muslims, their answers were fairly uniform. They viewed the presence of Muslims at the reading of the Commandments in terms that drew lines between the two religions, and even hinted at a reverse hierarchical relationship. Concretely, they claimed that “way down deep,” Muslims recognized the superiority of the Jewish religion, and the falsification represented by Islam. One statement, for example, was:

“They were the notables…who knew everything was false … they wanted to come and hear the truth, to assess at what level they stood…Their Quran was written by some person; we know that well…How it was written is known. [But the Torah], the Holy One Blessed be He gave it to Moses our Teacher, and he [gave it to] Joshua.20 That was the beginning… But the Quran was [just] written by someone.”

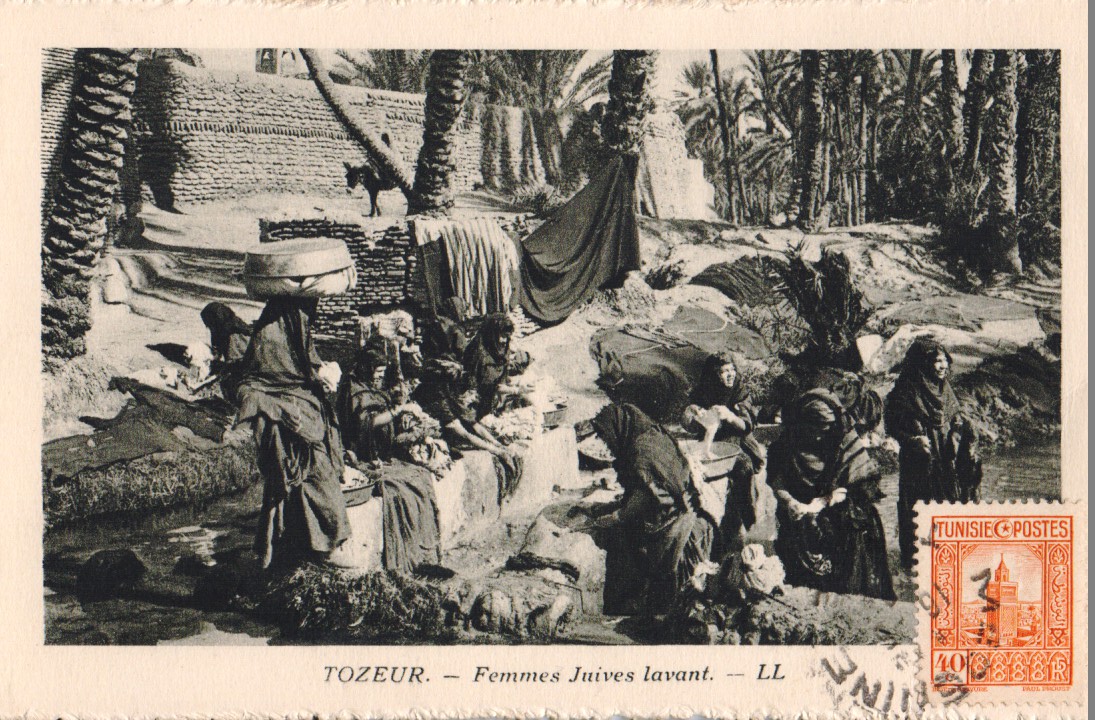

Tozeur, Jewish women laundering in wadi.

Courtesy of Tzivia and Yosef Tobi.

Another person, from Gafsa, stated: “The Muezzin [of the mosque], he certainly came. He was the first to come. They know that our Torah is the right thing. They know it is very good.”

And in another interview: “They certainly know [what the correct religion is]. But what? He was created as a goi21 and he has to respect himself and honor his parents, and has nowhere to flee. [But] they know. Some of them can speak openly and they say: ‘there is nothing like the religion of the Jews.’”

Another common notion in our interviews perceives the Muslim attraction to the Commandments in terms of pure human morality, summed up in Ten Statements with no religious exclusions. They represent moral truth, basic and pure, linking God with those who believe in Him. This was underlined in rhetorical connections that were repeated in the interviews. For example, when one person was asked what attracted Muslims to the Shavuot event he explained: “There is a Midrash about that. After reading to them and explaining to them in Arabic, they are full of amazement. Because what are the Ten Commandments: Do not Murder; Do Not Commit Adultery, all these things are explained to them.22 These are good Words. This is Education. …There is no hatred in this...no words of hatred. And they are amazed.”23

Yet another direction of interpretation arises from close attention to details of praxis entailed in the joint listening to the Commandments. The Quran, in Sura 7(143), recognizes a divine moment when the Israelites were “opposite the mountain.” But in the concrete setting of the reading in the synagogue, the ability to gain inspiration from a ritual performance of this foundational moment is mediated through the Jews. Here it is worth noting that the text of the piyyut is written in Hebrew letters that are transformed into Arabic only when read aloud by the chanter. Access to the content is available to the Muslims only through listening. In contrast, for Jews, the revelation first took written form as dramatically described in Exodus. In the specific ritual context we are examining, even though Islamic doctrine does not recognize contemporary Jews as true descendants of the ancient Israelites, a point of which our interviewees were aware, Jews still played the role of a living link between God and his believers. In our view, this nexus and the special place of Jews within it, reflects a wider pattern of what might be called a “religious ecology.”

It is possible to ask, for example, how Muslims knew when to come to the synagogue to listen to the Commandments. While it is reasonable to envision a prosaic reality in which they simply asked the local Jews, we suggest that within routine existence in North Africa there was an awareness of how the Jewish festivals were coordinated with the seasons and the agricultural cycle.24 This clearly contrasted with the cycle of the canonical Muslim festivals, and thus may have lent a sense of ‘origin’-ality or indigenousness to the framework of the Jews’ religion, beyond explicit matters of content regarding which the two religions differed. According to this perspective, there was a barely articulated correspondence between the religious primogeniture of the Jews and their deeply grounded cosmological power.

To conclude, an unexpected ethnographic testimony was the starting point of the research presented. In its wake, we embarked upon a journey into corners of memory still accessible among aging individuals from Tunisia and Libya who live in Israel today, in particular those who could recall synagogue life from the period before emigration. While there were differences among the interviews, they all ratified the existence of a practice whereby Muslims came to the synagogue on Shavuot to listen to a poetic Arabic translation of, and elaboration upon, the Ten Commandments. We have located this practice within a wider phenomenon of ritual mutuality linking Muslims and Jews in North Africa. This, in turn, led us to home in on central aspects of religious belief and symbols and their realization in praxis, even though we had no direct access to the voices of Muslim participants. Beyond that, the various explanations we encountered, and our own interpretative efforts, brought us to reflect on basic features of ethno-historical research: on its fruitful results along with its uncertainties.

1

This is a shorter version of a Hebrew paper entitled “Muslims in the

Synagogue: An Ethno-Historical Exploration of Joint Attention to a Hymn

(Piyyut) to the Ten Commandments in the Maghreb,” published in

HaMizrah HeHadash [The New East: Journal of the Middle East and

Islamic Studies] 55 (2016), 61-84. This English version is a

modification of an oral presentation delivered at the Tenth EAJS

Congress, Paris, 20-24 July 2014 and the “Beyond the Ghetto”

conference, hosted by Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, March 1-2/3

2016.

Harvey E. Goldberg is professor

emeritus in the Sarah Allen Shaine Chair in Sociology and Anthropology

at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His work focuses on the social

history of Jews in North Africa and questions of ethnic and religious

identity in Israel. More generally, he seeks to combine anthropology and

Jewish Studies. His publications include a translation from Hebrew of an

indigenous account of the Jews of Libya, The Book of Mordechai by

Mordecai Ha-Cohen (1993). He has authored Cave Dwellers and Citrus Growers

(1972), Jewish Life in Muslim Libya (1990), and Jewish Passages: Cycles of

Jewish Life (2003).

Hagar Salamon is Max and

Margarethe Grunwald Chair in Folklore and Head of the Graduate Program

for Folklore and Folk Culture Studies and Research Fellow at the Harry

S. Truman Research Institute for the Advancement of Peace at the Hebrew

University of Jerusalem. Her research focuses on cultural and identity

issues relating to Jewish communities (mainly the Ethiopian Jews),

present day Israeli folklore both in public and private spheres, life

stories and humoristic narratives as well as women's folk creativity.

Since 2004 she is co-editor of the journal Jerusalem Studies in

Jewish Folklore.

2 Literature on the topic is extensive; the following is a selection of sources. Antoine Fattal, Le statut légal des non-musulmans en pays d'Islam. Beyrouth, 1958; Hava Lazarus-Yafeh, Intertwined Worlds: Medieval Islam and Bible Criticism. Princeton, 1992; Mark R. Cohen, Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages. Princeton, 2008. Abdelwahab Meddeb and Benjamin Stora, eds., History of Jewish-Muslim Relations: From the Origins to the Present Day. Princeton, 2013. In the references that follow, we will mostly relate to sources concerning North Africa.

3 Lucette Valensi, “Religious Orthodoxy or Local Tradition: Marriage Celebration in Southern Tunisia.” In Jews Among Arabs: Contacts and Boundaries. Edited by Mark R. Cohen and Abraham L. Udovitch, 65-84. Princeton, 1989; Abraham L. Udovitch and Lucette Valensi, The Last Arab Jews: The Communities of Jerba, Tunisia. Milton Park, Abingdon-on-Thames, 1984; Harvey E. Goldberg, Jewish life in Muslim Libya: Rivals and relatives. Chicago 1990. Joëlle Bahloul, The architecture of memory: A Jewish-Muslim household in colonial Algeria, 1937-1952. Cambridge, 1996; Shlomo Deshen and Walter P. Zenner, eds., Jews among Muslims: communities in the precolonial Middle East. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire 1996; Yoram Bilu and Andre Lévy, “Nostalgia and Ambivalence: The Reconstruction of Jewish-Muslim Relations in Oulad Mansour.” In Sephardi and Middle Eastern Jewries: History and Culture in the Modern Era. Edited by Harvey E. Goldberg, 288-311. Bloomington and New York, 1996; Yoram Bilu, Without bounds: The life and death of Rabbi Ya'aqov Wazana (translator, Ruth Freedman). Detroit, 2000.

4 On Gafsa, see Haim Saadoun. “Gafsa.” Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World. Executive Editor Norman A. Stillman. Brill Online, 2015. Reference- Hebrew University, 25 October 2015. On the Judeo-Arabic dialect there, see H.-R. Singer, “Texte aus Südtunisien,” In Handbuch de arabische Dialekte. Edited by Wolfdietrich Fischer and Otto Jastrow, 271-276. Wiesbaden, 1980.

5 See F. Zuaretz, A. Guweta, Ts. Shaked, G. Arbib, F. Tayer, eds., Libyan Jewry, 380. Tel Aviv, 1960. (In Hebrew); M. Ji’an-Zarqina, “Special Customs among the Jews of Misurata (Libya).” In The Jews of Algeria and Libya. Edited by Moshe Halamish, Moshe Amar, and Maurice Roumani, 342-374. Ramat Gan, 2014. (In Hebrew).

6 For background, see Keith Lewinstein, “Commandments.” Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān. General Editor Jane Dammen McAuliffe. Brill Online, 2014. Reference. Hebrew University. 06 March 2014. The widespread stance of Muslims regarding the Torah is that the Israelites were recipients of God’s revelation, but over the generations Jews modified and falsified the text; see, for example, Lazurus-Yafeh, Intertwined Worlds. An additional perspective appears in Geneviève Gobillot, “Qur'an and Torah: The Foundations of Intertextuality.” In A History of Jewish-Muslim Relations: From the Origins to the Present Day. Edited by Abdelwahab Meddeb and Benjamin Stora, 611-621. Princeton, 2013.

7 Robert Brody. “Translating The Ten Commandments into Aramaic and Judeo-Arabic.” In Masoret veshinui betarbut ha’aravit hayehudit shel ymei habeinaim.” Edited by Joshua Blau and David Doron, 97ff. Ramat Gan, 2000. (In Hebrew).

8 Joshua Blau, “The Ten Commandments piyyut of Elazar ben Elazar (or Eliezer) attributed to R’ Seadiah Gaon.” In ‘Aseret hadibrot bire’i hadorot. Edited by Ben-Zion Segal, 327-332. Jerusalem, 1985. (In Hebrew). Other instances of this liturgical custom in North Africa are mentioned in the work of Tripolitanian scholar Avraham Adadi, “Quntres maqom shenahagu.” In Vayiqra Avraham, 127. Leghorn, 1849. (In Hebrew).

9 For a quick overview of this subject, see Harvey E. Goldberg, “Ritual Mutuality Between Jews and Muslims in North Africa.” Frankel Institute Annual 2013:19-22.

10 Mordecaï Ha-Cohen, Higgid Mordecaï: Histoire de la Libye et de ses Juifs, lieux d'habitation et coutumes (edité et annoté par H. Goldberg). Jerusalem, 1978. (In Hebrew); Harvey E. Goldberg (translator and editor), The Book of Mordechai: A Study of the Jews of Libya. London, 1993.

11 Harvey E. Goldberg, Jewish Life in Muslim Libya: Rivals and Relatives, 11-12. Chicago, 1990; Mordecaï Ha-Cohen, Higgid Mordecaï, 43-45, 284; Harvey E. Goldberg, Book of Mordechai, 74. London, 1993.

12 Harvey E, Goldberg, “Ecologic and Demographic Aspects of Rural Tripolitanian Jewry: 1853‑1949.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 2:245‑65, 1971.

13 Victor Turner, The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure, 109. Chicago, 1969.

14 The standard traditional practice in the Diaspora of celebrating the initial day of the three pilgrimage festivals is for two days.

15 Our interlocutor here used the Hebrew devarim, the plural of davar, which can be translated as ‘thing’ or as ‘word.’ ‘Devarim’ is the term used three times in the Hebrew Bible in connection with the ‘commandments,’ while in rabbinical terminology (and in modern Hebrew), it became common to refer to ‘aseret hadibrot’ (the trliteral stem db(v)r also constitutes the verb ‘speak’). The title of the Arabic piyyut chosen by Blau is el-`ashar al-kalamat (see note 7, above), and kalamat also can be translated simply as ‘words.’ Our translation does not seek to be totally faithful to all the linguistic details of the recorded text, but attempts to convey somewhat the complexities of meaning embedded with the answers we received.

16 Sheikh, head of a local community; Mudir, head of a district; Qadi, judge.

17 The tradition of publicly translating the reading of the Torah began in antiquity when it was translated into Aramaic; in the Middle Ages the practice of translating into Arabic built upon that. In some instances, the two practices coexisted. See the article of Robert Brody in note 6, above.

18 We cite here the view of our interlocutors. In the article by Joshua Blau (see note 7, above), he does not view the Judeo-Arabic piyyut as representing a high register of Arabic.

19 Daniella Talmon-Heller, “Reciting the Qur’an and Reading the Torah: Muslim and Jewish Attitudes and Practices in a Comparative Historical Perspective.” Religion Compass 6/8 (2012): 369–380. DOI 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2012.00351.x ].

20 The interviewee’s words here parallel the opening pericope of the Mishnaic tractate Avot.

21 In the spoken Judeo-Arabic of the Jews in Tripolitania, the loan-word (from Hebrew) ‘goi’ specifically meant a Muslim (not a Christian).

22 We offer a speculative interpretation as to what this interviewee might be referring to when he bases his explanation on “a Midrash.” There is an ancient homiletic tradition regarding receipt of the Ten Commandments that pictures God first offering the Torah to other nations, and their refusing it because they do not want to accept precepts like “do not steal” or “do not murder.” An example of this tradition appears in the midrashic commentary on Deuteronomy, Sifre, Paragraph 343. Our interlocutor may be (intuitively?) reversing the content of this tradition, accommodating it to the concrete experience of non-Israelites who enthusiastically identify with the commandments.

23 Continuing our speculation as to what traditional Jewish textual associations might inform the interviewee’s explanation, there exist liturgical expressions of hostility toward enemies of the Jewish people. One example is found in the Haggadah, the text accompanying the ritual meal on the first night of Passover. The text offers midrashic “multiplications” of the number of plagues that afflicted the ancient Egyptians at the time of the Exodus, reaching as high as 250 plagues instead of the 10 appearing in the Bible.

24 For example, in Morocco many Muslims were well aware of the period during which Jews made special food and dietary preparations for Passover, and were alert to the end of the holiday as well. See Harvey E. Goldberg, “The Mimuna and Minority Status of Moroccan Jews.” Ethnology 17:75‑87, 1978. In Tripolitania, some Muslims designated Jewish celebrations by local Arabic terms that reflected observable public features of the holidays. As Yom Kippur approached, Muslims spoke of ‘id ad-džaža, the holiday of chickens, corresponding to the widespread slaughtering of chickens for kapparot ceremonies that preceded the fast day, and ‘id ez-zriba, the holiday of palm branch huts, the common Arabic term among Muslims for the Jewish festival of Sukkot.