The Jews of Cyrenaica During World War II, in Their Own Words

Vivienne Roumani-Denn1

Benghazi to Camp Giado

The Jews of Libya, especially those of Benghazi and the rest of the eastern province of Cyrenaica, suffered greatly during the Second World War. The facts have been recounted in texts by De Felice2 and Roumani3 and in an article by Simon.4 My goal here is to give those who experienced the events an opportunity to tell the story in their own words. In 1998 and 1999 I recorded oral histories of Jews from Libya, most of whom were living in Israel, and in 2003 and 2004 I recorded video interviews for my documentary The Last Jews of Libya. I have also conducted additional interviews, both between these projects and since. The interviews were variously in Italian, Hebrew, Arabic, and English, many involving linguistic shifts during the conversations. The translations are my own. Those who lived through the war had vivid memories, despite more than fifty years having passed since the events. I have included here only descriptions of events that are consistent with other testimonies and/or the archival record. I have also included relevant excerpts from an unpublished memoir by my mother, Elise Tammam Roumani,5 completed sometime before 1987, which we found after her death and which provided the narrative structure of The Last Jews of Libya.

Racial Laws

Laws affecting Jewish business owners were instituted in Libya in late 1935 and the Italian racial laws were applied in 1938, despite efforts by the Italian governor, Italo Balbo, to mitigate the impact because of the importance of the Jews to the economy. “The bakery shop Nelle Pasticceria had a big sign outside: Vietato l’ingresso ai cani e agli ebrei [Entry prohibited to dogs and to Jews].”6 Jews were ordered to open stores on the Sabbath. “They had to open. . . . They opened the shop and they left a boy or a girl from the family to stay there. If a buyer came they said sahaba dacan mushga'at [the owner of the shop is not here at the moment]. . . . But things got tougher later on, and the owners were forced to come to their shops. They tried to avoid selling, but . . . they had no choice.”7

Beginning of the War

The war in North Africa began in September, 1940, with an Italian invasion of British-held Egypt. Male Jews living in Libya who held British passports were considered to be enemy aliens and were placed in internment camps; those from Cyrenaica were taken to a camp 140 km from Benghazi. “They took those with an English passport to a village called Zuwaytinah, and they stayed there like brothers.”8 “One afternoon they gathered up all the adult men who were British subjects and they took them to a camp. . . . The families used to visit, but they were allowed only one hour with them. As their time there dragged on the Chief Rabbi brought them a Sefer Torah. And they brought them books . . . it was a tough time, really. . . . When the British came they liberated them. Most of those British subjects, the men, fled to Egypt [when the British subsequently retreated].”7

Much of the North African War was fought in the Eastern Libyan desert, and the port of Benghazi was crucial to both the Allied and Axis supply lines, hence it was bombed heavily by whichever side was not in control. “I remember a bombardment . . . in which twelve or thirteen Jews died. When there were bombardments all the families [in Benghazi], . . . all of the Jews, went to the desert, built shacks, and lived there. Because the bombardments were at night and in the city . . . [When the Italians] left the English came; when the English left the Germans came.”9

From my mother’s memoir: “The British planes were bombing, especially at night. The Marina shelter was in the Piazza Municipio, and as soon as we heard the sirens everyone would run to the shelter to take cover. We heard the bombs falling, and we spent hours and hours there; we didn’t know what to do, where to escape. . . . Tired of the situation, we tried first to go to Kuwayfia [13km northeast of Benghazi], then to Qaminis, a small city outside of Benghazi [55km south], about two hours away; we could hear the bombing, but they didn’t bomb there because there was nothing of military interest. Every couple of days the men went to the city, and they came back at night bringing news of what had happened during the preceding days. One day Joseph came back with his cousin, Sasi Duani. They were drinking coffee quietly. . . . They told me that the previous night there had been bombing in the Piazza Municipio and that the British tried to bomb the Marina shelter, since it contained war documents, but the bomb fell in full on our home; when Joseph arrived there with the key in hand to open the door, it was shattered. They went in, and the bedroom was all destroyed; the furniture that was so beautiful and new was in pieces. Only the chandelier was saved, held up by the headboard of the bed. So the next day I went there and I retrieved some clothing and some kitchen items. We tried to fix the door, then we returned to Qaminis. On a Friday afternoon an order came to leave Qaminis in less than one hour, and so it was.”5

Benghazi changes hands

The British drove the Italians back across the eastern desert and occupied Benghazi on February 6, 1941. The Jews welcomed the British, whose troops included Jewish soldiers from Palestine, “gave them a big celebration, the Jews. We gave them to drink, to eat.”11 The British then withdrew on April 2 following the arrival of Rommel’s German Afrika Korps, and many Jews with British passports fled with them. On April 3, with no government in place, Jewish homes and stores were ransacked in revenge. “There were looters in Benghazi on the third of April, 1941 . . . There was general looting of all the Jewish stores and houses, by the Italians and not the Arabs. It may be that Arabs also took part, but it was a small number. . . . all of the looting was done for revenge by the Italians against the Jews, because during the English occupation of Benghazi the Jews dealt with the English. That was a normal thing, something that could not be avoided – you have to have commerce, you have to work. But in the eyes of the Italians, they saw this as collaboration with the English.”10 From my mother’s memoir: “The third of April, 1941, was an unforgettable day. The British retreated and the city had no government. The Arabs, as well as some Italians, pillaged the city, the market and especially the stores of the Jews, which were burned and looted. [The rioting was largely by Italians.] Certainly no one could go out, nor even look out the window. There was a curfew at night. My mother had Italian neighbors. One of them . . . came to stay with us at my mother’s home and brought us food . . . . Many people . . . . followed the British, since they had British passports, . . . including my sister in-law Massaouda and her family.”5

“An English official knocked at my door on the night of April second [and] said ‘we are leaving the city, if you want to cut the cord.’ I had bought a small car, a Topolino 500. My father, my mother, my wife, my daughter, and I left in this Topolino. My brother left with another car. . . . We arrived in Egypt, after changes along the road, and bombardments, . . . and we stayed in Egypt.”11

The British captured Benghazi again in December of 1941, but this time the Jews were more circumspect in dealing with them. They retreated once more in January of 1942, and many of the remaining British subjects in Cyrenaica left with them.

Starting in January, 1942, Libyan Jews holding British passports, together with other British citizens, were sent to internment camps in Italy. Some later ended up in Nazi concentration camps, including Bergen-Belsen, following the fall of Mussolini. This aspect of Holocaust history was relatively unknown until recently. Consider this account from Yossi Sucary: “When I was nine years old, I grew up in a very Ashkenazi neighborhood in northern Tel Aviv, and on one of the memorial days of the Holocaust the teacher talked about the Holocaust, and I said that my family was in the Holocaust as well. [They were among those sent to Bergen-Belsen]. … She told me it’s not true, that only the European Jews were in the Holocaust. So I went to the principal of the school, and I told him I knew from my mother and grandmother that they had been in the Holocaust. He told me that the teacher was right. . . . For two and a half years I thought that my mother and grandmother had lied to me. It was amazing; it was a difficult experience. That’s why I wrote [the book and play] Benghazi–Bergen-Belsen.”12

Expulsion of the Jews of Cyrenaica

On February 7, 1942, Mussolini ordered the removal of all Jews from Cyrenaica, a process that took place between May and late October. Those holding French (typically from Algeria) or Tunisian nationality were transported by truck to Tunisia. “The group was three hundred families. They were split at the border of Tunisia between Tunisian and French. The Tunisians remained in Tunis and the suburbs, and the French . . . were spread all over Algeria – every two or three families were placed somewhere. The Bramlis, for example, were in Constantine. And Guetta, a relation of my mother, was in another place, called Tebesa . . . . ”7 From my mother’s memoir: “At the end of September, 1942, we left for Tunis. We left the rest of our furniture at the house of my in-laws, which belonged to a very trustworthy Arab who worked with Joseph with his flock. The things of value we buried. . . . We took a few pieces of jewelry with us. We were the last ones to leave, the last truck. . . . We arrived in Tunis the day of Rosh Hashanah, where they placed us in a school of the Alliance.”5

Giado

Between May and October about 2,600 Jews with Libyan nationality, together with about fifty Italian Jews, were sent in trucks to a former military camp in Giado (Jadu), a village in the mountains 200km southwest of Tripoli. Another four hundred were sent to villages in the mountains of Tripolitania. Lists of those to be transported were posted in the synagogue. “When the government came to the president [of the community] . . . and told him ‘we want the list of all the Jews’ . . . he said ‘we don't keep books, we don't keep lists,’ and [a member of the community] . . . said ‘I've got the lists’. . . . That's why he was afraid to come to Israel.”7

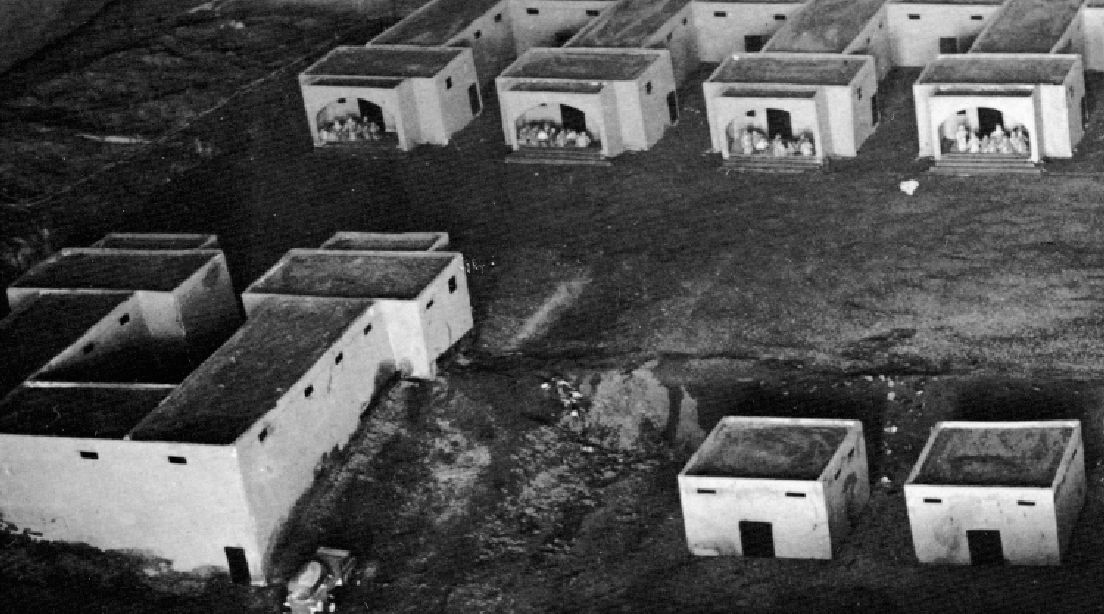

Conditions in Giado, which was run by Italians, with Italian and Arab guards, were very bad, and more than one in five died, mostly of typhus. “I remember when they took . . . all my family to Giado. . . . The Italians took all the Jews. . . . At that time I was still small. The head of the community at that time was the Chief Rabbi . . . they took him in the third or fourth group . . . I remember very well. It was a concentration camp, surrounded by barbed wire. There was a Maresciallo Capo [chief marshal]. There was a big dormitory – it was an open dormitory. There was space given to each family, divided by curtains. I remember very well.”8

“[They] came to take us to Giado. . . . They did not tell us where they were taking us. They said we have to take all of you, and they did. There was dirt, flies. . . . The buildings were like army barracks. In each barrack there were about 40 families squeezed together. Just blankets separated each family. The Maresciallo came every night. . . . Each family was together; each big area had about forty to sixty families, one next to the other. Some died from hunger and disease. When we tried to eat a piece of bread we had to fight through the bugs. . . . I came there pregnant; my daughter was born there, and then she died there.”13

“There were carabinieri – like police. They were Italians and an Arab, and they guarded us from outside the fence, which was electrified. One of them was a major, with boots and a whip for horses. He would go into the camp, into the barracks. How was it divided? Well, every family took a three by four meter area inside and hung blankets. No beds – we slept on khsera [mats], like sardines. These mats are like thin bamboo. . . . We had no blankets because we used them for walls. . . .”

“They wanted to kill all of us. We got sick. There was hunger. We had no food. We got a piece of bread, like a small roll, round, made of maize. Everyone ate half of one. We were six people and we got three rolls. My mom gave hers to my brother. The younger ones got them. I didn’t eat, because I could make do. . . .’ [The Jews in Tripoli] would send us fish, and bread, because there was not enough. Their situation was not that good, either. The major would say ‘the shipment will not be allowed in today’. He would punish us.”14 “They gave fifty grams of bread per day, black bread. . . . There was an Arab market. They came to Giado on Thursdays and Fridays, twice a week. And the Jews would sell their things to get some food. . . .”8 (Simon4 reports that the bread allocation was 100 to 150 grams/day, with a weekly distribution of some rice or pasta, tomato sauce, oil, sugar, and tea or coffee. Some food and money was also sent from the Jewish community in Tripoli.)

“We got the tifo pidochiosso [lice typhus]. Seven hundred to nine hundred died from it. . . . We had lice. They would cover us. They were white. . . . When the British came they took [the blankets] because the lice lived in the blankets. I remember it well. I was thirteen. I had my bar mitzvah there.”14 “They took us to a concentration camp, Giado. It was very difficult. They made us suffer, both my wife and I. We were fifteen. There was no food. The bread was full of bugs. There was typhus, and many died. We were there one year and eight months. There was a rabbi with us; they pulled him by his beard, dragged him to the floor to pick up [crap], and they hit him on the back.”15

'Model of the Italian Fascist Concentration Camp at Giado, with thanks to Vivienne Roumani-Denn, and to the Museum of Libyan Jewish Heritage, Or Yehuda, Israel, owner of the model, for kind permission.'

There was a common belief that the Italian King Victor Emmanuel III had issued an order to make the Jews in Giado suffer, but not to kill them. Here is one recounting: “The Italian King Emmanuel III told them ‘you will not kill the Libyan Jews. They are not European. They don’t know anything. I am responsible for them. You will not kill them. Punish them, yes’. They took us to the camp, and they punished us there. All we did was clean the camp [including cleaning latrines4]. We had no strength. People were not moving, except the young ones. There was no school or anything. . . . [The carabinieri] just hit us. We did nothing all day. We had no strength. . . . We all believed. We had emunah [faith]; we would say Tehilim [psalms] and pray, in hiding. We would take our garbage out. The camp was an old French camp in the hills, with horses. We would dump the garbage over the hill.”14

There was a terrifying incident reported by all of the interviewees who had been in Giado that probably occurred close to the time of liberation. “One day they brought all the camp to the square, and they had machine guns there, like in the movies. In a truck, four of them. I was young, twelve years old. I didn’t know what it was. But there was an order from the King not to kill us.”14 “One day – I remember that day very well, I was fourteen or fifteen – they gathered all the men together and said they had to come to the middle of the camp. I remember that day. My mom hid me. . . . All the Jews, all the women, the children, the women were crying. . . . I went to see, and I saw all the police, the Captain, both Arabs and Italians. I saw them and I ran away. I fell and hurt myself very much. . . . it became infected [His leg was amputated].”8 “They collected all the men and pointed guns at them. They wanted to kill them. The King of Italy said no, don’t kill them.”15 “One day they came to take us to this big place, all of us. They put us in a circle, and they brought that thing, like a machine gun, that they put in the middle to kill us all. They crowded us together. They were going to kill us. They prepared us for slaughter. After fifteen minutes a call came from the King of Italy. He said ‘make them suffer but don’t kill them’. The Commandant released us and took the elders – the rabbis, the hachamim [learned men] – and told them to sweep the floors with their beards, and that’s what they did. On their stomachs on the floor!”13

The Jews of Benghazi who were sent to towns in Tripolitania fared better. “We Jews from Benghazi, because of the war, were deported to a concentration camp called Giado . . . until there was no more space. Then in the second phase, the Jews were taken to Gharian . . . not very far away, near Tripoli [80 Km from Tripoli]. We were not in a concentration camp. . . . Everyone rented a house or an apartment, but we were always under the surveillance of the carabinieri.”10

The British drove the German and Italian armies back across the Libyan desert in October, 1942, and they captured Tripoli in January, 1943. “Alfonso Barda, the director of a driver's agency . . . came to me and said ‘We have a request from the community of Tripoli to go to Giado . . . Do you know that place?’ I said of course. I worked there when they built Giado. The Italians built the camp for the war against the French. This concentration camp where they took the Jews of Benghazi was an Italian military camp not far from the Tunisian border. He said ‘Benedetto, we need to go to bring food from Tripoli to Giado’. They had just liberated the concentration camp, and the English had not yet arrived. I arrived there when the Italian police were still commanding at Giado. They sent me with two Jews from Benghazi. . . . They came with me because their families were in Giado; they wanted to help. . . . We loaded with food, and . . . two big jugs on top. I began to drive on Thursday afternoon. . . . It started pouring . . . all night. [He describes getting stuck in wet sand and being helped by South African soldiers.] When I arrived at Giado, the people from Benghazi who knew me came to greet me. There was also a cousin of mine from the family of Teshuba. They all came to hug me. Then an Italian police marshal gave me a slap. . . . I fell down. I no longer had any strength after the mud and the trip. The English had not arrived in Giado yet. They heard that they were liberated, but the Italian police saw a Jew bringing them things . . . Then they took the things and we returned. No, [the Italians] did not steal any food.”16

“Two British came. Initially they appeared to be against us. They went to the Commandant, they ate, they drank, they checked what was going on in the place. At the end it was clear that they came for our well being. They ate and slept at the Commandant’s, but they showed him an order that he had to send us back to our country, and if he didn’t, he would go to another world. So we were sent back.”13

“When the British came we could not leave the camp. They kept us [there] and cleaned us and our clothes. They stripped us naked, the English. The doctors had masks. We had the illness and they were afraid it was contagious. The Joint [the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee] sent food in cars with Magen Davids. We ate and got stronger and went back to Benghazi.”14

“When we came back [from delivering food to Giado] I started working. Then, they told me that I must bring back a group of Jews who had been in Giado to Benghazi. . . . the British brought them from Giado to Gharian . . . a military camp outside of the caves. . . . It took us three or four days on the road, and we returned with English military men who then occupied Tunisia. . . . We were four Jewish drivers and there were two Catholics and one Arab, so there were seven cars.”16

Tunisia

The Cyrenaican Jews who were sent to Tunisia in the summer and fall of 1942 had only a few months of respite. “We were in Tunisia hardly three months and then war began. . . . We rented a house in La Goulette. It was small, but we were content to escape the bombing, because Tunis was being bombed. . . . One day we were all in the house, one studying Tehilim [psalms], the other studying Torah; we were all at home; there was no work. Then we heard the airplanes. . . . They bombed La Goulette. It was a disaster, but thank God we were saved. We left the house in La Goulette, and we went to La Marsa. . . . We were there as if we were on a holiday trip, not a trip of desperation. My mother made couscous, and there was good wine; they drank and laughed and had a good time. [Most of the refugees in La Marsa, who had arrived earlier, were housed in one large building.] All of a sudden [on March 10, 1943] they came to bomb La Marsa. They said La Marsa would never be bombed because the Bey [monarch] lived there. … There was shrapnel that fell like pieces of glass. About forty of us from Benghazi were hit. Small, young, old; my two brothers, my sister, and her fiancé were among them. They were killed arm in arm, as if they were going for a walk. And my mother … I took two more steps and I saw my brother Rahamim, with his arm all bloody, and he was telling me ‘Rachel, Rachel, don’t worry, stay calm, stay calm.’ Then my sister Giulia came and took him … to the hospital. …. He was without an arm for the rest of his life … It was a disaster. It was a period of one hour, but that hour was a century.”17 Thirteen members of my father’s family died in that attack. Maurice Roumani, who experienced the bombing as a young child, recently established18 that the bombs fell from American aircraft and had been intended for a nearby airfield.

Return

The Jews in Giado were freed and returned to Cyrenaica. Those who had been deported to Tunisia or Italy trickled back, as did some of the British passport holders who had left in 1942. They found a change in their relations with their Arab neighbors: “Some Arabs of the old generation who knew us tried to help. But their children wanted nothing to do with us.”4 “We took ten families, by bus … We went back [from Tunisia]; we paid for the trip. … When we came back we only found walls. Nothing else. They even took the tile; even that the Arabs took. And the bathroom fixtures. They didn’t leave anything – only the walls. … People came and rebuilt everything. Life [in Benghazi] was very difficult. It wasn’t like before. [I] was very nervous … I didn’t feel free to live. I didn’t accept that my freedom had been taken away by those around me.”9

1 Vivienne Roumani-Denn is an oral historian, writer, and documentary filmmaker. She served as the Judaica Librarian at the University of California, Berkeley, where she created the website www.jewsoflibya.com in 1998, and as the Executive Director of the American Sephardi Federation at the Center for Jewish History in New York, where she founded the Sephardic Library and Archives and the Exhibition Gallery. Roumani-Denn’s documentaries The Last Jews of Libya (2007), narrated by Isabella Rossellini, and Out of Print (2013), narrated by Meryl Streep, both premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival.

2 Renzo De Felice, Ebrei in un paese arabo: gli ebrei nella Libia contemporanea tra colonialismo, nazionalismo arabo e sionismo (1835-1970), Il Mulino, Bologna, 1978; published in English as Jews in an Arab Land: Libya 1835-1970, translation by Judith Roumani, University of Texas Press, 1985.

3 Maurice M. Roumani, The Jews of Libya: Coexistence, Persecution, Resettlement, Sussex Academic Press, 2008.

4 Rachel Simon, The Jews of Libya on the Verge of Holocaust (in Hebrew), Peamim, 28 (1986): 44-77; Published in French as Les Juifs de Libye au seuil de la Shoah, Translation by Claire Drevon, Revue d’Histoire de la Shoah, vol. 205 (2016), No. 2, pp. 221-262.

5 Elise Tammam Roumani, unpublished memoir, written some time before 1987.

6 Stella Rubin, 1999.

7 Joseph Tammam, 1999.

8 Haim Gerbi. 1998.

9 Chlafo Romano, 1998.

10 Felice Sasson Legziel, 1998.

11 Saul Legziel, 1998.

12 Yossi Sucary, 2015.

13 Giora Roumani, 2004.

14 Moshe Giuili 1998.

15 Sassi Guetta and Rina Nahum Guetta (joint interview), 1998.

16 Benedetto Arbib, 1998.

17 Rachel Luzon, 2004.

18 Maurice M. Roumani, First, Libya’s Jews were deported. Then the S.S. stepped in, Haaretz, February 8, 2020; last accessed March 1, 2021.