Indemnification for Libyan Jews after 1943: A Special Case?

By

Jens Hoppe1

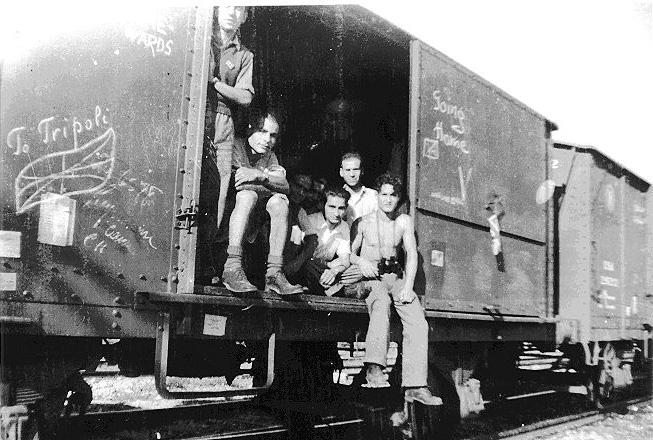

Returning to Libya from Bergen-Belsen by train, 1945. Courtesy of Yad Vashem archives.

Since the beginning of World War II, some Jews pondered the possibility of receiving indemnification from Germany after an anticipated Allied victory. Soon after November 1941, it became clear that indemnification should be paid to European Jews and already in 1943 the idea of a collective payment arose.2 The first plans, however, focused on German Jews.

When Libya was finally liberated by the British in January 1943, the fighting in Europe and Asia was still underway; the end could not be foreseen. No concrete plan for indemnification for Libyan Jews existed then, as far as we know. After the German Reich was defeated, the first indemnification laws in the late 1940s focused on the surviving German Jews in the American, British, and French occupation zones, and also in the Soviet occupation zone in Thuringia. The western Allies put pressure on the West Germans to include at least some non-German Jews in the plan. Such indemnification at that time was considered part of the reparation question and, therefore, connected to a coming peace treaty, and only peace treaties with Italy and other German allies could be concluded in 1947. Foreign Jews like the Libyans were not seen as part of the German indemnification issue at this time.

Thus, the first West German federal indemnification laws of 1953/1956 included the following groups of Jews and gentiles (sections 4 and 149 Federal Indemnification Law, Bundesentschaedigungsgesetz/BEG):

- Persecutees from Germany (in the borders of December 31, 1937) plus

the city of Danzig;

- Persecutees who stayed in a DP camp on the territory of WestGermany

on January 1, 1947;

- Persecutees from the so-called “Vertreibungsgebiete” (i.e., the

areas in central and eastern Europe from which ethnic Germans were

expelled after the war), who had a German language and cultural

background (in German: “deutscher Sprach- und Kulturkreis”);

- Stateless persecutees (as of October 1, 1953); and

- Refugees according to the Geneva Convention of July 28, 1951.

The last two groups had only limited rights, but still, at least they could receive something from the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG).

Jews from Libya did not fit into any of these groups because they did not live on German soil or in Europe. They had, of course, no German language or cultural background, and they were usually not stateless or refugees. Why then did they finally receive indemnification from Germany? Did they get payments from another state? Or to ask it differently: Who paid indemnification for what?

In the following article, I focus on German payments to Libyan Jews after 1956. This also includes payments for former forced laborers made by the German Remembrance, Responsibility and the Future foundation (Stiftung Erinnerung, Verantwortung und Zukunft/EVZ), which was established in 2000. Because other players were active in the indemnification field as well, I also take a very brief look at Great Britain, Italy, France, and Israel. One additional major player was a Jewish organization established seventy years ago in New York City: The Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany. What the Claims Conference did will be discussed also.

The Wehrmacht, the German army, actively fought the Allies in Libya and also in Tunisia. In Algeria, Vichy France had its own anti-Jewish persecution. From the onset in 1940, the German occupation forces put pressure on the French Vichy government to persecute Jews not only in metropole France, but also in its colonies and protectorates. To understand the specifics of the Libyan case, indemnification payments for Tunisian as well as for Algerian Jews have to be considered. It must be said that the following cannot be all-inclusive. No matter how many details are presented, important parts of the story regrettably will be missing.

Germany

Section 43 of the German Indemnification Law of 1956 determined that an individual who was persecuted outside of the German Reich by a foreign state in defiance of constitutional principles and following German instigation during World War II could receive payment for deprivation of liberty. The question with regard to the Libyan Jews is, were these requirements fulfilled? When the German parliament enacted the BEG, the persecution of Jews on North African soil was not on its agenda. Very soon after 1956, however, Italian measures against Jews in their occupation zones and colonies became a legal issue. According to the above law, the main questions were did Italy persecute Jews due to German instigation and were the Jews incarcerated under neglect of fundamental laws. In 1958, the Frankfurt Higher Regional Court (Oberlandesgericht/OLG) ruled that the imprisonment of Jews in metropole Italy is compensable due to German instigation and because they were incarcerated only because of being Jewish; racial persecution by itself means neglecting fundamental laws.3 The German Federal Supreme Court (Bundesgerichtshof/BGH) agreed with this decision in 1960.4 The BGH states that arrest only because of being Jewish infringed on fundamental laws of all democratic states (in German, Kulturstaaten). It also agrees with German instigation on a juridical point of view. Instigation is defined here as German demands in general, not for a specific measure. The incarceration of Jews in a camp certainly fulfilled the German wish for sure. Dr Alfred Schueler, a lawyer working for the United Restitution Organization (URO), first in London and after 1956 in Frankfurt, commented on the BGH decision. According to Schueler, the Federal Supreme Court defined instigation as follows: “Neither coercion nor subordination is required. An initiative, a suggestion is sufficient, and they can provoke an unlawful act of a sovereign, independent state.”5 He also quoted a 1959 BGH decision in which this court ruled that German instigation can be assumed if a measure lies in the general sense of the German demand. Incarceration of Jews always fits that definition. Unfortunately, the situation for Jews who were incarcerated by the Italians during the Second World War was not that clear.

Around 1960, the German states Hesse, Berlin, and North Rhine-Westphalia paid indemnification to survivors who were incarcerated in the Italian camp Ferramonti di Tarsia, but Rhineland-Palatinate rejected them. The 1962 URO publication, “Persecution of Jews in Italy, Italian occupied areas, and in North Africa,” supported indemnification for Jews incarcerated by the Italians.6 It presented documents of German instigation. This work clearly shows that the URO included the Libyan Jews at the beginning of the 1960s. According to URO circular 889/62 of February 14, 1962, this published collection was sent to relevant governmental departments of the FRG and of the states, to indemnification offices, and to courts with Italian-related proceedings, especially Koblenz, Neustadt/Weinstrasse, Mainz, Trier, Frankenthal (all Rhineland-Palatine), Cologne, Frankfurt, Munich, Stuttgart, Karlsruhe, and Celle. As a result of these efforts, all the German states finally agreed to pay indemnification for Jews incarcerated in Ferramonti di Tarsia. But some courts still passed negative judgments in the 1970s. Hanna Yablonka wrote that around 3,500 Libyan Jews had received indemnification payments with the help of the URO.7

According to the OLG Koblenz decision of March 17, 1978, more than 2,000 Libyan Jews had gotten an indemnification payment for incarceration in Libya, some as late as 1974, 1975 or even 1977.8 If the number of 2,000 is correct, who are the missing 1,500? According to Ettore Bastico, Italian governor of Libya, some 1,600 French Jewish subjects and members of the protectorate of Tunisia lived in Libya. Until August 1942, the Italians had deported 1,861 Jews, along with some Muslims, to Tunisia.9 Most of the Jews were incarcerated by the French Vichy administration of Tunisia in three camps: Gabès, Tniet-Agarev near Sfax and Marcia Plage (or Marsa Plage) near Tunis. According to the OLG Cologne, the incarceration of Jews in these camps resulted from anti-Jewish persecution by the Vichy-oriented French Protectorate authorities, and took place due to German instigation.10 Therefore, Jews from Libya with Tunisian citizenship received German indemnification payments. Those with French citizenship were rejected because of being citizens of a state with which West Germany reached a global agreement. They had to request indemnification from the French government. We will see later why Libyan Jews with French citizenship did not get a payment.

It is unknown to me how many Libyan Jews who had been incarcerated in Tunisia received a German payment in the 1970s. The majority of the 1,600 Jews mentioned above held Tunisian citizenship. Most probably, around 1,000 should be added to the 2,000 noted above. That said, some five hundred of the 3,500 reported by Hanna Yablonka remain missing. It’s unclear, for what kind of persecution the missing five hundred have received a BEG payment with the help of the URO.

In the 1990s, the persecution of former forced laborers became a topic not only for historians but also for politicians inside and outside of Germany. In particular, the U.S. government was involved in putting pressure on the German government to pay some kind of indemnification to living former forced laborers, mostly non-Jewish. Finally, the German foundation EVZ was created to pay up to 15,000 Deutsch Mark (7,669 €) to them. The EVZ did that with the help of so-called partner organizations like the Claims Conference or the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Before the payment process began, a meeting of experts from the partner organizations and the EVZ in January 2001 discussed the living conditions of many camps outside the S.S. concentration camp system to determine which should be included in the program. The Giado camp in Libya was seen as concentration camp-like (KZ-like) by these experts; an expert opinion, however, was needed regarding the Buqbuq camp. Finally, in November 2001, Giado was officially recognized by the EVZ foundation as a so-called other camp (German, “andere Haftstaette”) so that Jews who were incarcerated there in 1942/1943 could receive the EVZ payment of 15,000 Deutsch Mark (in Euros). Nonetheless, not all camps on Libyan soil, such as Sidi Azaz, were recognized by the EVZ.

Great Britain

In the early 1940s, the Italian authorities arrested Jews with British citizenship in Libya. In 1942, at least four hundred and twenty British Jews were deported to Italy and incarcerated there in civilian internment camps. After the Wehrmacht occupied most of Italy in September 1943, these Jews fell into German hands.11 In documents of that time, they were called “Bengasi Jews.” According to Alexandra-Eileen Wenck, the first eighty-three were sent to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp on January 31, 1944. The next transport including seventy Libyan Jews reached that KZ on February 24, 1944.12 When the next two groups with together one hundred and forty-seven Jews were deported from Italy to Bergen-Belsen in May 1944, some of the first transport had already left that camp; they were included in a German-British prisoner exchange. Sixty-six of the “Bengasi Jews” left Bergen-Belsen on February 18, 1944, but only forty-nine were brought to the internment camp Vittel in France. That camp was used by the Germans as the main starting point of prisoner exchanges. The missing seventeen had to remain in the Liebenau camp in Germany. On July 1, 1944, another seventy Libyan Jews reached Vittel.13 The other one hundred and sixty-four had to stay in Bergen-Belsen until November 1944, when they were brought to the Wurzach camp in southern Germany via Liebenau.

In May 1964, eight years after Great Britain had demanded a payment for indemnification of British subjects persecuted by the Germans during the Second World War from West Germany, both countries signed a global agreement. The FRG paid one million British pounds (GBP), around 11.2 million Deutsch Mark (DM). The British government defined who was entitled to get an indemnification payment:

National Socialist persecution means the infliction by members of the National Socialist Party or their agents for reason of race, religion, nationality, political views, or political opposition to National Socialism of treatment involving detention in Germany or in any territory occupied by Germany in a concentration camp or in any institution where the conditions were comparable with those in a concentration camp. Hardships suffered in a normal civil prison, civilian internment camp or prisoner of war camp do not constitute Nazi persecution nor does treatment contrary to the Geneva Conventions and the rules of war, even though resulting in permanent injury or death.14

Based on this definition, Libyan Jews could receive a payment, but not for the time in Italian civilian internment camps. Only being held in a German KZ like Bergen-Belsen made them eligible for indemnification. Unsurprisimgly, the British government, like the German parliament a decade before, had not thought about the persecution of North African Jews. Most probably, the British Embassy in Tripoli brought up their situation first.15 Based on 1966 lists about “Compensation for Nazi Persecution,” Libyan survivors of the Bergen-Belsen camp got 408 GBP (around 4,570 DM) for their incarceration. Some of them lived in the U.K. (London), Italy (Rome and Pescara), or Israel (Netanya), while others still resided in Tripoli.16 The final exodus of the Libyan Jews took place only one year later17 and those left their home country then.

Italy

In March 1955, the Italian government enacted a law for “Welfare measures for political persecutees for reasons of anti-Fascism or race.” This law provided for a welfare pension, not an indemnification for survivors or their heirs .18 In the mid-1950s, the Italian government denied any racial persecution of Jews by the Italian Fascist government.19 Hence, it is not surprising that Jews persecuted by the Fascists did not receive indemnification from the Italians. Like Great Britain before, in 1957 the Italian government demanded a payment for indemnification of its subjects persecuted by the Germans during World War II from West Germany. Four years later, West Germany paid forty million DM as part of a global agreement between these two countries. The crucial Italian decree of October 6, 1963, defined eligibility as follows:

Entitled are Italian citizens, no matter if they were arrested inside or outside of Italy, who were deported to national socialist concentration camps (Italian, campi di concentramento nationalsocialisti) for reasons of race, faith or ideology.20

Based on this ruling, neither Italian Jews nor Jews with foreign citizenship incarcerated by the Italians in Libyan camps were eligible. Also, the Jews with British citizenship deported to Italy by the Italians in 1942 could not get a payment for their incarceration in Italian camps on Libyan or Italian soil. Of particular importance in the 1961 global agreement is that West Germany agreed on the readmitting of applications of Italians for the BEG and the Federal Restitution Law (Bundesrueckerstattungsgesetz, BRueG) respectively, upon reviewing already received applications. Thus, the door for Libyans may have been opened.

France

The French authorities in Algeria began with financial restitution and restoration of jobs and material assets to reverse economic crimes of the Vichy government in 1943. The Jews had to claim their losses on an individual basis.21 According to a French law of 1948, Jews with French citizenship could receive payments if they were deported and incarcerated by the Germans during the war. Thus, In June 1956, France demanded a global payment from West Germany in favor of French citizens who had been deported and incarcerated in German concentration camps. Both countries reached an agreement of about four hundred million DM for French victims four years later. The French government decreed in August 1961, that only French citizens (as of July 15, 1960, which is the signing date of the global agreement) could receive an indemnification payment if they had been incarcerated by the Germans in camps on French soil or in German KZ outside of France. This also applied only to individuals who had not already gotten any German indemnification payment.22 Jews who were persecuted, like all others, were eligible only if they have gotten the French “carte de déporté politique.”

France did not pay indemnification for internment therein to Jews deported from Libya to Tunisia and incarcerated in the above-mentioned camps of Gabès, Tniet-Agarev, and Marcia Plage. These camps were established by the French Vichy protectorate authorities in the summer of 1942, and therefore, they were not recognized as “German concentration camps.”

Israel

West Germany and Israel reached the so-called Luxembourg agreement in 1952, in which the Germans agreed upon paying three billion DM to Israel, to be paid in yearly installments until 1965. The state of Israel, however, had a price to pay: Israeli citizens could not receive a German payment for damages to their health if they reached Israel before October 1, 1953.23 Hence, Libyan Jews who lived in Israel received a one-time payment for damage to liberty (e.g. due to incarceration in Giado) from Germany, but not a pension, no matter how severely their health was affected during the persecution or in the aftermath as a consequence of the former persecution. If survivors wanted to receive the latter, they had to make a claim under the Israeli Invalids Nazi Persecution Law of 1957. The requirements of that law were directly connected to the German BEG criteria.24 In retrospect, it is hardly understandable why Israel based a law in favor of Shoah survivors on a German law. As a result, health damage pensions for Libyan Jews were paid by Israel regulated by German-defined criteria. The Israeli Ministry of Finance payments for Libyan survivors became independent from German BEG rulings only after 2000. For example, according to the German BEG, a survivor could get a payment due to flight from his hometown only in case s/he reached an unoccupied country or liberated area. This was not the case if a Jew left one Libyan place for another. But Israel paid a Libyan survivor also in case he left his hometown for another place inside of Libya because of fear of German actions. Hence, while the Israeli government focused on leaving the hometown due to the anti-Jewish persecution, that is the starting point of the flight, the German law focused on reaching an unoccupied area, that is the end of the flight.

Claims Conference

Since 1980, the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany administered a so-called Hardship Fund (HF). Like the 1957 Israeli law, the HF eligibility criteria were based on the BEG. The HF paid 5,000 DM (or, since 2001, 2,556.46 €) to Shoah survivors worldwide. One basic rule, established by the German Ministry of Finance at the time, was that an applicant who had gotten a BEG payment was not entitled to receive HF. The same was true for so-called Western persecutees, i.e., British citizens were not eligible. Hence, many Libyan Jews were ruled out: not all have received a German or British indemnification payment. Some, however, did receive the HF payment for incarceration because they hadn’t claimed under BEG in the 1960s. In 2010, the German Ministry of Finance agreed to pay HF to Jews who had to live under a special curfew for Jews during the persecution. Some, thus, received the one-time payment because they had to live under this curfew for Jews.

Based on Yad Vashem’s Pinkas ha-kehilot Luv, the Claims Conference could pay HF to Libyan Jews who had not received a BEG payment, from the communities of Amrus, Barce (El Merdj), and Zliten.25 This is also a good example of the linking of (published) historical knowledge about the anti-Jewish persecution in a certain area and the change in eligibility criteria. Because the HF and other Claims Conference programs are based on BEG criteria, the German Ministry of Finance recognizes camps and/or other types of persecution only after the Claims Conference could provide positive BEG court decisions, German states' agreements regarding certain camps or persecution types, and/or historical knowledge about the situation of the persecuted Jews in a place, country/area or camp. Hence, the Pinkas information on a curfew for Jews in some Libyan communities was the needed precondition here.

The Claims Conference knew very well that a pension which offers ongoing financial help is much more important to Shoah survivors than a one-time payment. Therefore, the organization asked the German Ministry of Finance for a pension fund. After the German reunification, the government of the FRG agreed on the so-called Article 2 Fund. Beginning in 1995, the Claims Conference paid pensions to survivors of camps and ghettos or who had livedg in illegality, in hiding or under false identity for long-time. In 2002, the Claims Conference succeeded in recognizing Giado, Sidi Azaz, Buq Buq, and the “little camps” around Gharyan, in Jefren, in Tigrinna, and in Gharyan itself, as KZ-like. This helped Libyan survivors who were still alive sixty years after their liberation by the British to get a pension from Germany via the Claims Conference.

Tunisian Jews

The French protectorate authorities in Tunisia became Vichy-oriented in the summer of 1940. Therefore, the Jews living in Tunisia were subject to anti-Jewish persecution. With the German and Italian occupation in November 1942, Tunisia became a battlefield of the Second World War and the Jews had to face German persecution, too. The Italians protected only their Jewish citizens. All others (with the exemption of Jewish citizens of neutral states like Portugal or Switzerland) had to pay contributions, lost household goods, and had to do forced labor for the Germans inter alia. After the liberation in 1943, the question of indemnification came up here, too. The German courts decided in unison that the internment of Jews in metropole France and the North African colonies and protectorates was a result of German instigation.26

According to section 31 BEG, a pension due to damage of health was assumed only if the persecutee was incarcerated in a concentration camp for at least twelve months. Because the Germans occupied Tunisia only for seven months (November 1942 and May 1943) and the first labor camps were built up only in December 1942, the Tunisian Jews could not receive a BEG pension on basis of an assumption. They only could receive the one-time payment for loss of freedom. But the French citizens were ineligible because they were considered so-called Western persecutees. Most of the Tunisian survivors did not apply for indemnification under BEG at all. Thus, the Tunisian Jews, in contrast to the Libyans, did not get indemnification from the FRG.

After 1980, the Claims Conference HF received applications from Tunisian survivors, mostly living in France or Israel. The organization decided that former Tunisian forced laborers could get a HF payment because in accordance to BEG section 47, they were compelled to wear armbands identifying them as Jewish. The EVZ started to pay former forced laborers, when it was decided in February 2004 that Tunisian labor camps could be recognized as KZ-like in keeping with the Claims Conference’s detailed report on twenty-seven camps Hence, Tunisian Jews incarcerated in one or more of these camps could receive the maximum payment of 7,669 €. The camps were also recognized under the Article 2 Fund, enabling living survivors to receive a pension at the earliest since 2005. Since 2007, survivors from some communities, including Kairouan, Monastir, Nabeul, and Sousse, where the Germans forced the Jews to wear a yellow star could also receive the HF payment.

Algerian Jews

Susan Slyomovics has discussed the topic of indemnification and the Jews of Algeria in her book How to Accept German Reparations.27 Here, I will focus only on a few items relevant to comparing the situation of the Algerian Jews with that of the Libyans. As mentioned above, the German instigation for incarceration of Jews in camps on Algerian soil was acknowledged by German courts. This was but one step. The second is the citizenship question. Foreign Jews incarcerated in these camps did receive a BEG payment for loss of liberty. The French citizens were excluded, disregarding the abrogation of the Décret Crémieux in 1940, and forced to request the French government for indemnification according to the 1960 global agreement. France, however, did not pay indemnification to camp survivors in the second half of the twentieth century. Still, according to Slyomovics, “in 2007, the French National Assembly again underscored its refusal to assign Algerian Jewish interned conscripts under Vichy the status of bearers of a political internee card (carte d’interné politique).”28

The Claims Conference requested the recognition of Algerian camps by the EVZ foundation. Just as with the Tunisian labor camps, the EVZ recognized thirty-six camps in February 2004, and all Algerian and foreign Jews still alive (as of February 16, 1999; section 13 EVZ foundation law) who were incarcerated in one or more of these camps could receive the maximum payment of 7,669 €. These camps were also recognized under the Article 2 Fund, enabling living survivors to get a pension as early as 2005. The Claims Conference reached an agreement with the German Ministry of Finance in 2018, to include Jews who resided in Algeria between July 1940 and November 1942, when the Allied troops landed, and were persecuted by the French Vichy-authorities in the HF.29

Conclusion

Is the Libyan case a special one? Since the late 1950s, the organizations of the Libyan Jews in Israel have fought actively for the indemnification of former Giado inmates. Hanna Yablonka wrote that Libyan Jews saw themselves as an integral part of the Shoah at a very early stage and thus, should be entitled to compensation from Germany.30 In Israel, because the 1957 law was strongly connected to the German BEG, the Libyan camp survivors finally got payments, too . Only decades after the enactment of that law, Israeli courts left the “German way” in favor of the Libyans and, thus, more survivors became eligible for Israeli payments.

Other North African communities were neither active like the Libyans nor did they have the same point of view. With regards to the BEG, the Germans also recognized camps in Algeria. Because of the citizenship issue, only the non-French inmates of these Algerian camps, mostly former German and other central European Jews, received indemnification payments. So, the Libyan quota of BEG recipients was much higher than the Algerian: While more than 3,000 Libyan Jews, around eight per cent of the Jewish population at that time, received a BEG payment due to their incarceration in a camp, only a few hundred Jews living in Algeria received a similar payment, which is less than one per cent of the Jewish population of Algeria in 1940.

Taking into consideration indemnification payments from Western states like France and the U.K., again the Libyan Jews with British citizenship received payments in the 1960s, while the Tunisian or Algerian Jews with French citizenship did not. The U.K. also paid only for incarceration in German concentration camps, not for the time in Italian ones. The Italians never paid survivors for being incarcerated by the Italian Fascist government. This clearly shows that the national socialist persecution of Jews was appraised very differently from the Fascist persecution, and the approach of Vichy France. Only the first was seen as inhuman and a specific evil. On the one hand, this conclusion is accurate. On the other, it was used to minimize the persecution of Jews by other Fascist governments and to deny the responsibility of some states for their racial persecution and injustice.

Later, the differences between the Libyans and the other North Africans continued to persist. Tunisians were the first to receive payments under the Claims Conference HF program in the 1980s. The Libyans followed only later; many had gotten BEG payments and therefore were excluded from the HF program. But the Algerians were the last. Interestingly, the German EVZ foundation recognized Giado in 2001, but Algerian and Tunisian camps only three years later. This reflects the BEG history.

So, the answer to the question raised above is clearly, yes. Internal and external factors shaped a very specific indemnification history of Libyan Jews. The external factors are the government of the FRG including the individual states, the German courts, the British, the French, the Italian, and also the Israeli governments. The main internal power was the organization of the Libyan Jews themselves, in Israel. In addition, the URO fought for the Libyans since the early 1960s, as did the Claims Conference since the 1990s. These Jewish organizations helped Libyan Jews receive a small measure of justice.