The history of Iraqi Jews as told by an Iraqi Muslim Author

Book Review and Commentary

By Nimrod Raphaeli1

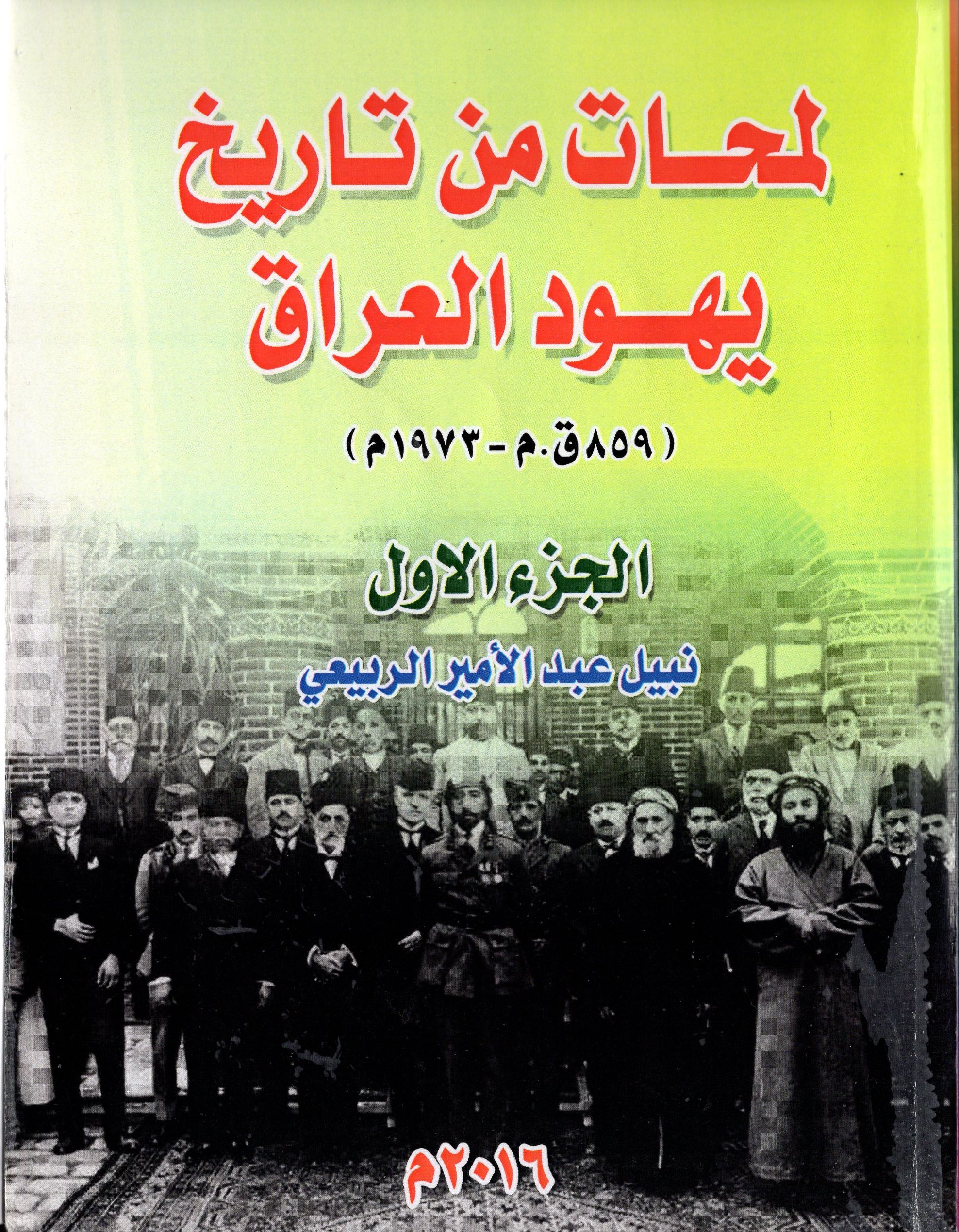

The newly-installed King Faisal visiting the Jewish community in 1922.

To his left, is the chief rabbi (designated by the Ottoman authorities as Hakham Bashi).

The term was still in use until the final exit of the Jews from Iraq.

Nabil Abd al-Amir al-Rubei’i. Lamahat min tarikh: Yehud al-iraq (Glances from the History of the Jews of Iraq-- 859 BC-1973). 2 Vols. Hilla, Iraq: Dar al-Furat Le-thaqafa, 2016

Personal Note

Books published in Iraq are not easily accessible to the Arabic readers in the United States. Let me explain how these two volumes came to my possession.

In 2002, Washington, D.C. was invaded by a large group of Iraqi political and military figures, opponents of Saddam Hussein, eager to take part in what was anticipated to be a major U.S. military action in their country. Stories were flying about as to who was most likely to be the new leader of Iraq and who might occupy a key post in the post-Saddam Hussein era. I was fortunate to meet a number of these individuals and with one in particular I struck up a personal friendship. He was a former general in the Iraqi armored corps which participated in the invasion of Iran in 1980, and took part in many subsequent battles. Not surprisingly, he had never met a Jew, but he recalled his mother mentioning often the good Jewish doctor who took care of the family. In one of our conversations, I mentioned to him that my family owned palm groves in a place called nahr jassim (Jassim River) located about halfway between the Iraqi and Iranian border. There was so much fighting in that area, he told me, that the Jassim River was dubbed nahr al-dimaa (The River of Blood). My friend, who lived in exile and who attained the rank of major-general, went back to Baghdad after the invasion but for personal reasons he was in the U.S. often and he would call me for a coffee and a chat. When I read about the publication of the book under review, I called him at his home in Baghdad and asked him whether he could get the two volumes. He did and the books were delivered to me courtesy of another friend. I was curious as to why anyone would publish, in 2016, two large volumes on Iraqi Jews when there were virtually no Jews left in the country and very few Arabic readers outside the country among Jews whose roots are in Iraq. He said he was curious as well and asked the bookstore owner that same question. He was surprised by the answer, although the answer confirmed what I have gathered from reading the Iraqi press over decades: particularly among the older Iraqi generation, there is considerable yearning for a minority that had contributed so much to the development of the country in so many areas and there is a feeling that, after their forced departure, Iraq has never been whole again.2

I should point out at the outset that the book under review is well-researched and meticulously referenced. Other than referring to Israel here and there as the Zionist entity (al-kiyan al-sahioni), a term pejoratively used by Iran and some Arab writers, the author generally avoids polemics, even when he describes the life of Theodore Herzl and his role in the creation of Zionism. Iraqi Jews themselves acted as loyal Iraqi nationals and the Zionist creed was not, as we would say today, on their radar screen, but things would change dramatically in the 1940s, ushering in periods of violence and state-sponsored anti-Semitism.

This review will focus primarily on the first of the two volumes, which provides an impressive coverage of the long history of the Babylonian Jews and the origins of Judaism and the transition of Jewish life from the Babylonian era through the various Islamic, including Ottoman, rules up until the present day when the last remaining piece of contention is the Jewish Archive (see later). The book provides remarkable details, including names of hundreds of individuals and the significant role they played in the life of Iraq through the centuries, while also dwelling on the various acts of violence to which the Jewish community was subjected by various rulers up to and through the early days of Saddam Hussein, when almost no Jews remained.

Jews and Islam

The history of the Jews before the advent of Islam with all its religious context has been covered extensively in other works. What is unique in this work, and the focus of this review, is its coverage of Jewish life in Iraq since the advent of Islam in the 7th century.3

After facing a lot of oppression under Persian rule, the Iraqi Jews, numbering 90,000 in 636 AD, welcomed the advance of Islam into Iraq as a liberating force. As members of a monotheistic religion, the invaders from Arabia treated the Jews well and, in fact, several Jews were assigned to high positions in the administration of the country.4

As is common in the history of the Jewish people, there are high tides and low tides in terms of their relations with their rulers. During the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad Jews enjoyed a good measure of freedom in the exercise of their religion until suddenly "in a fit of zeal" in 807 the Khalif Harun al-Rashid ordered non-Muslims’ places of worship "to be razed to the ground." A historian of the era Reuben Levy points out that notwithstanding the khalif’s order, the Jewish exilarch "maintained some show of authority and had certain privileges." Moreover, Jews were left free to practice in the fields of finance, medicine and the arts as well as to trade in the bazaars. In these areas of endeavor the non-believers, Christians and Jews, "had the city to themselves."5

In the second half of the 7th century, new rules were issued against the people of al-dhima by which they were required to wear special clothing, they were prevented from riding a horse (limited instead to riding a donkey or a mule) and their children were excluded from attending Muslim schools or getting instruction from a Muslim teacher. One official went as far as grading Jews and Christians as falling between Muslims and beasts. These discriminatory measures were viewed by the author as an attempt to convert the dhimis [Christians and Jews living under Islamic rule] to Islam.6

Jews under the Moghuls

The Abbasid caliphate came to an end with the fall of Baghdad into the hands of the Moghuls in 1258. The Moghul soldiers went into an orgy of murder and destruction against all the residents of Baghdad without exception. Once the orgy was over something happened that one might call ‘ness min hashamayim’, a miracle from heaven. A Jewish doctor by the name of Sa’ad al-Dawla became an adviser to Moghul Sultan Oragon (1284-1291). The doctor provided such sound advice to the sultan he was placed in charge of the treasury of the Moghuls with authority over small as well as big matters. He was able to appoint his brothers as walis (or governors) in Baghdad and in the northern city of Mosul. Poets were so effusive in their praise of the doctor that, according to legend, their poetry filled an entire volume. However, Sa’ad al-Dawla went too far. After he cut allowances to the mosques, Muslim imams prepared a document in 1290 using verses from the Koran to prove Jews were a community “disgraced by Allah.” The Muslims rose against the Jews for three days of plunder and murder, the doctor being one of the victims.7 Still, as the author observes, despite all they suffered in terms of discrimination and violence the Jews never considered leaving their country. This is certainly true through the 1940s of the last century.8

Jews under the Ottoman Empire

Beginning in 1520 and for the next four centuries, Iraq came under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. With few exceptions, the Jews encountered little discrimination during the Ottoman era. In fact, both Jews and Christians enjoyed a period of tranquility and tolerance. The economic conditions had noticeably improved and the Jews could build synagogues and open schools. In the mid-16th century, Itshak Sarfati, a local Jewish leader, sent a letter to Jews in Germany and Hungary urging them to visit the land of the Turks and then proceed safely to the Holy Land.9 While there were no demographic studies, of course, some visitors estimated the number of Jewish families in Baghdad in the 16th century at 3,000.10

While the Jewish community was granted a considerable degree of freedom to manage its affairs, there were nevertheless some demeaning restrictions. There were 42 Walis (governors) who ruled Iraq during the Ottoman period. Most were friendly toward the Jewish minority but under the few who were hostile, they might be denied the right to wear cloaks over their clothing, to ride horses in the city, or to touch fruits and vegetables in the market; they might be required to keep a distance from Muslims while walking the streets or forbidden to wear the color green, a sacred color for Muslims.11 Despite some occasional outrageous behavior against them, the Jews under the Ottoman Empire were granted full legal jurisdiction over their community and indeed many Jews occupied senior positions in the Ottoman government in Iraq. By the 19th century, wealthy Jews began to acquire agricultural lands and acted as landlords like the Muslims of the country.12

By the 18th century Jewish merchants and entrepreneurs began to establish new trading bases in Calcutta (currently Kolkata), Bombay (Mumbai), Singapore and Hong Kong. The author reminds us that what went well ended in a disaster. Shortly before the fall of Baghdad to the British army in 1917 the representative of the Ottoman Wali (governor) and his chief of police arrested a few Jewish money changers for allegedly speculating with the value of the Turkish lira and causing its collapse. These poor men were subjected to “hideous torture, their ears and their noses cut off, their eyes gouged out, and their bodies placed in bags and dumped into the Tigris River.”13

In all fairness, it should be remembered that during the Spanish Inquisition, the Ottoman Empire provided safe harbor for Jews expelled from Spain.

The Jews Welcome the British Army

As the Ottoman Empire begun to crumble toward the end of World War I, the Jews, as mentioned earlier, were victimized for supposedly causing the collapse of the government’s finances. Not surprisingly, the Jews welcomed the British army when it entered Baghdad victoriously in 1917. There is evidence, Rubei’i maintains, that shortly after the military government was established, the Jews of Baghdad sent an appeal to the military governor of Iraq, General Stanley Maude, signed by 56 leading personalities in the community, expressing their objection to the creation of a Arab national government and requesting to be to granted the status of British subjects.14 In anticipation of the arrival of the British army, according to the author, the Jewish community in Baghdad slaughtered enough cows, sheep and camels to provide meals for 500,000 soldiers, an expectation which the author notes was greatly exaggerated.15 I should note that while this is a good story I have not found support for it elsewhere.

With their language skills acquired at the Jewish schools and what today would be termed a globalized outlook, Jews in large numbers were recruited by the British military government to fill many positions in the new administration. Other Jews used their trading skills and overseas contacts to import food supplies to meet the needs of the British army.

The Transition to National Government

With a deadly revolt by the tribes of Iraq in the center of the country in 1920 against British rule Great Britain proceeded quickly to arrange for the transfer of power to a national government. The first and most critical step was to install a king. Prince Faisal, whose father was the emir of Hijaz (Saudi Arabia today), was installed in Iraq by the British following a plebiscite that earned the approval of a vast majority among a largely illiterate population. In his first speech as a king, Faisal declared “there is no meaning for words like Jews, Muslims and Christians within the concept of nationalism. This is simply a country called Iraq and all are Iraqis.”16 Jews were admitted to all levels of government and one of their prominent figures, Heskell Sassoon (later knighted), was made the first minister of finance of the country. He is well remembered to this day for his contribution to the establishment of a modern administration in Iraq and, above all, for his strict integrity and probity. From the first parliamentary election up to their mass departure from the country, Jews were guaranteed four seats in the lower house and one seat in the upper house. As the author Rubei’i points out the Jews of Iraq were never confined to a ghetto although there were sectors of Baghdad and other big cities like Basra and Mosul with a large Jewish majority.17 Most surprising of all is the existence still today of a small street named Jewish lane (‘agd alyehud) in the Shiite holiest city of Najaf.18

Iraqi Jews prospered under the kingdom both domestically and internationally. In addition to the economic empire established by the Sassoon family, Iraqi Jews occupied high positions in other countries. The author mentions Edward Sheldon (Shamash) as a minister in the Labour government of Britain in 1974 and David Marshall (Misha’l) as the first prime minister of Singapore in 1954. One should also mention Siegfried Sassoon, a leading British poet. The author also mentions Saleh Hardoon and Eliezer Khadouri who established economic empires in China and later in Hong Kong.19

The Farhud (1941)

The most dramatic and tragic event in the modern history of Iraqi Jews is the Farhud (June 1-2, 1941). Incited by the mufti of Jerusalem Haj Amin al-Husseini who sought refuge in Iraq after being expelled from Palestine by the British, and by the German ambassador to Baghdad Fritz Grobba, and a conniving pro-Nazi Iraqi government under Rashid Aali al-Gailani, a violent mob attacked Jewish homes in Baghdad and plundered their businesses. Soldiers and members of the police force took part in the mayhem. By the time order was restored, 180 Jews had been murdered and close to two thousand injured, women had been raped, and any Jewish businesses had been looted or destroyed. The Farhud, which Rubei’i attributes to the nature of the Iraqi society20 and to the incitement of Palestinians,21 was a turning point in the history of the Iraqi Jews as it drove home the realization that the future of the community had become at best cloudy. While the Farhud was followed by a period of relative prosperity, the United Nations resolution in 1947 calling for the partition of Palestine and the creation of two states triggered anti-Jewish government-sponsored measures that made life for the Iraqi Jewish community unbearable.

The Mass Immigration

Unlike the Jews of Egypt and the Jews of North Africa who identified with French language and culture, the Iraqi Jews were thoroughly Iraqi in terms of history, culture and language. Zionism had not been on the agenda of many Iraqi Jews, but this situation dramatically changed when the State of Israel was established and anti-Jewish and anti-Semitic manifestations both in words and action intensified. I remember a chant heard daily and repeatedly on the national radio station—the only radio station in the country:

Tel abib tel abib sawfa tusla belaheeb walyahud walyahud, sawfa yakunun al-woqud

[Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv will be destroyed by flames and the Jews the Jews will become the firewood]

Jewish bank accounts were frozen, Jewish employees in the government were fired, real estate transactions were forbidden, universities closed their doors to Jewish students, and life, in general, became intolerable and often dangerous as many Jews were arrested and sentenced to long terms in prison for alleged Zionism or espionage for Israel. Encouraged by representatives of the Jewish Agency, young Iraqi Jews, both boys and girls, sought the way out by using smuggling routes through Iran (with the help of the Shah). It is estimated that 3,000 Jews were smuggled into Iran illegally.22 The government of Iraq reached the conclusion that the only way to put an end to the illegal exit was to let go those who wanted to leave Iraq. There may have been a cynical aspect underlying the new policy. The Iraqi government believed that inundating a young and poor country like Israel with tens of thousands of immigrants would cause it to collapse. In 1950 a law was promulgated by the Iraqi parliament that allowed those willing to leave Iraq to surrender their citizenship [in a process termed tasqit]. The assumption was that only a few thousands of Iraqi Jews would take advantage of that opportunity to surrender their nationality and leave the country. To the surprise of many, the vast majority of Iraqi Jews, in fact as many as 105,000, chose to leave. An American chartered airline carried these mass immigrants to the new but impoverished State of Israel. The British Embassy in Baghdad estimated that the mass exit of Iraqi Jews would undermine the Iraqi economy where 75 percent of all imports and a lot of the foreign and domestic trade was handled by the Jewish community.23 In March 1951, with most Jews having left the country, the government passed a new law freezing all Jewish properties and assets. Rubei’i calls the act a second ‘Farhud’.24

The Iraqi Jews under the Republican Regime (1958-1974)

Following the mass immigration of Jews to Israel there remained in Iraq about 6,000 Jews some of whom remained because of their strong pro-Iraqi orientation and others who simply waited for opportunities to go to countries of their choice. The military coup in 1958 and the rise of General Abdul Karim Qassim to power signaled a major change in the life of the Iraqi Jews beginning with the removal of restrictions on their travel abroad. Many of them did take advantage of the opportunity to leave and sought refuge primarily in the U.K., Canada and the United States. The situation changed again for the worse with the rise of the Ba’th Party to power in Iraq in 1963. Following the Six-Day War in 1967 most commercial, academic and social doors were shut to Jews and many were arrested for allegedly posing a danger to the security of the country. By then, there remained only 3,250 Jews in the country. In October 1969 nine innocent Jews, including a sixteen-year-old boy, were accused of espionage for Israel and hanged in the central square of Baghdad. Their bodies remained on the gallows for a whole day to afford an enthusiastic mob an opportunity to celebrate25 during what Saddam Hussein was to call “a historic day.”26 In 1973, after two years of secret negotiations, Saddam Hussein agreed to give the remaining Jews of Iraq passports ostensibly for tourism purposes provided a payment of $1200 was made for the each passport. The deal was done and only a handful chose to stay behind. A major chapter of Jewish history was closed.

Brief Review of the Second Volume

The first volume offers a narrative history of Jews in Iraq. The second is more like a reference work describing the various aspects of Jewish life in Iraq including religious practices, cultural life, the graves of prophets, locations of synagogues and a meticulous listing of Jews categorized by professions and commercial activities, often accompanied by photographs, in the major cities of Iraq. A lot of space is also devoted to Jewish schools and Jewish education and their significance in preparing a professional class that was in demand through the many Muslim rules and the British military administration. The amount of detail is extraordinary and suggests a meticulous study of records still available in Iraq and of works in Arabic by Jews outside the country.

The author describes accurately all the Jewish holidays—Purim (incidentally he mentions the Fast of Esther which falls a day before Purim), Pesach, Rosh Hashana, Yom Kippur, Succoth [Feast of Tabernacles], Shavuot and Hanukah with detailed explanation about the significance of each and how it was celebrated by the Iraqi Jewish community. He goes on to review practices of marriage, divorce, inheritance, brit, Bar Mitzvah and even the use of Mikvah (religious bath).27 I found the breadth of the coverage amazing given that the author is a Muslim who may never have met a Jew in his life.

The author dwells extensively on the mausoleums of Jewish prophets providing the historical background and the details of their physical structure and accompanying each with a photograph. With the departure of the Jews, the Muslims have converted most of these religious sites often with impressive mausoleums into mosques.28 Unfortunately, almost all synagogues were either destroyed or turned into storage places. Jewish cemeteries were almost entirely razed.

The Jewish Archive

The Iraqi Jewish Archive is a collection of 2,700 books and tens of thousands of historical documents from the Iraqi Jewish community. The collection was found by the United States Army in the basement of Saddam Hussein’s intelligence headquarters during the U.S invasion of Iraq in 2003, brought to the U.S. for restoration, and has remained in U.S. custody. There is disagreement as to whether it should be returned to Iraq where only a handful of Jews have remained, or it should be kept in the U.S. or even in Israel to allow easy access to the original owners of the material and their descendants. The author seems to share the concerns of the Iraqi Jewish community in the diaspora that the Iraqi record of preserving their antiquities and other historical assets leaves much to be desired.29

Concluding

In an obituary published in the Washington Post of the Tunisian Jewish writer Albert Memmi he is quoted in his novel “The Pillar of Salt” as declaring: “I am a Tunisian but of French culture.”30 No Iraqi Jewish writer or novelist would have declared: “I am an Iraqi but of ‘whatever’ culture.” Iraqi Jewish writers, like the entire Jewish population that lived in Iraq, considered themselves an integral part of the Iraqi society and the Arabic language culture. Iraqi Jews were fully integrated into the Iraqi society, the Iraqi economy and Iraqi political life. It is not surprising that so many of them served their country at all levels of government positions.

At the same time, Rubei’i makes an important concluding observation. While the Iraqi Jewish community was integrated within the Iraqi society, he says, they kept their “private practices on matters of marriage, divorce, circumcision as well as playing a big role in the economic growth of Iraq thanks to their financial strength and their contacts with world traders.”31 Rubei’i graciously mentions that “the sons of the Jewish community” participated with the Iraqi people in all the upheavals and the social protests against the government. They left, he said, their own “martyrs.”32

And a final personal note: Iraq today is a failed country and I have been asked many times about my feelings regarding the situation there. I am of two minds on the subject with a mixture of nostalgia and relief. Nostalgia about a country that was our home for generations with many cherished memories as well as anxieties. It is a relief because knowing what has happened in Iraq under the dictatorship of Saddam Hussein followed by occupation and civil war, the Jewish community would have been the first to suffer. It is a wonderful feeling to have a safe harbor in the United States

1 Nimrod Raphaeli is Senior Analyst Emeritus at the Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI). He formerly worked at the World Bank from 1969-2000.

2 As early as 2002 MEMRI published a booklet by Y. Segev titled “Narratives and ‘New’ Narrative about the Iraqi Jews’ Emigration [Immigration] to Israel.” The booklet quotes extensively from several Iraqi journalists writing favorably about the Iraq Jewish community.

3 Some references of interest would include: Nissim Rejwan, The Jews of Iraq -3000 years of History and Culture. Boulder, Colorado, Westview Press, 1985; Nissim Kazzaz, The Jews in Iraq in the Twentieth Century, [Hebrew]. Jerusalem, Ben Zvi Institute, 1991; Mordechai ben Porat, To Baghdad and Back [Hebrew] Or Yehuda: Maariv Book Guild, 1996; Moshe Gat, A Jewish Community in Crisis—The Exodus from Iraq, 1948-1951[Hebrew] Jerusalem, The Zalman Shazar Center, 1989; and Orit Bashkin, New Babylonians, A History of Jews in Modern Iraq. Stanford, California, Stanford University Press, 2012. Also, worth mentioning are two books in Arabic. Yusuf rizqallah Ghanima, Nizhat al Mushtaq fi Tarikh yehud al-Iraq [A Longing Journey--History of the Jews of Iraq,] London Warrak Publishing Ltd., 2nd ed. First published in 1924; Yacoub Yusuf Kuriya, yehud a-iraq—tarikhahum, ahwalahum, hijratahum [Jews of Iraq, their history, conditions and immigration]. Amman, Jordan, al-ahliya lilnashr, 1998 (printed in Lebanon) Vol.1, pp.46-7.

4 Vol. 1, p. 71

5 Reuben Levy, A Baghdad Chronicle, Cambridge University Press 2011, first published in 1929. The quote is from Nimrod Raphaeli review of book for Sephardic Horizons 4:1 (Winter 2014).

6 Pp.74-75

7 P.99

8 P.100

9 P.106

10 P.107

11 P.113

12 P.124

13 Pp.112-113

14 P.155

15 P.157

16 P.165

17 P.168

18 P.171

19 P.150

20 P.174

21 P.182

22 P.223

23 P.225

24 P.257

25 Pp.344-345

26 P.348

27 Vol.II, pp.63-85

28 Vol.II, pp.20-25

29 Vol.II, pp.306-309

30 May 31, 2020

31 Vol.II, p.317

32 Vol.II pp.317-318

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800