Review Essay

The Jewish Community of Ioannina, Greece

Recent and Not So Recent Publications

By Annette B. Fromm1

Scholars have long taken an interest in various aspects of Sephardic Jewry, Jews whose origins trace to the fifteenth century expulsions from the Iberian Peninsula. Early in the twentieth century, linguists were entranced by the discoveries of antiquated Spanish preserved in Balkan towns in the form of ballads, proverbs, and more. Compendia of texts were published in Spanish and other language journals. Additional studies written in a number of languages have followed, documenting aspects of traditional culture and history of Sephardic communities especially in the Balkans. Emphasis has been on the more populated, more significant community of Salonika.

Jews have lived in Greece since classical times. Archeological evidence in the form of Hebrew inscriptions documents their presence there as early as the late fourth century BCE.2 There were established communities in Salonika, Chalkis, and on Crete in the first century BCE. Benjamin of Tudela noted Jews in several locations including Corfu, Patras, Corinth, Thebes, Chalkis, and Salonika. Their presence in Ioannina is traced to the Byzantine period. From the fourteenth century through the present, there has been a continuous Jewish presence in this northwestern provincial capital as well as the surrounding towns.

By the early 1990s, several ground breaking conferences were organized in the U.S. and elsewhere. Three convened at the State University of New York Binghampton, organized by Drs. Norman and Yedida Stillman, and at the University of Iowa, planned by Dr. George Zucker. A number of scholars attending also made presentations about non-Sephardic communities that existed in the midst of the larger Judeo-Spanish groups at these meetings. I was one of these, speaking about topics related to the Greek-speaking, now called Romaniote, community of Ioannina, Greece. Two of these gatherings resulted in significant publications documenting the research approaches at that time.3 They consist of essays on topics ranging from the role of Spanish exiles in the Ottoman Empire to Sephardic philosophy and cover geographic areas from the Balkans to North Africa to Argentina.

When the Spanish and Portuguese exiles reached the Ottoman Balkans they found long-standing communities of local, Greek-speaking Jews. In cities where the Judeo-Spanish speaking Sephardim predominated, the so-called Romaniotes assimilated to their minhag and traditional culture. The community in Ioannina, in northwestern Greece and neighboring smaller towns remained relatively untouched by the Iberian diaspora and retained their Greek-centered heritage. Relatively little has been written about this community. In the past decade a few works, three books and a film, have appeared. They are the primary subject of this essay.

Several scholars writing generally about Greek Jewry have included information about aspects of the Ioannina community. Steven Bowman refers to Ioannina in some of his many publications about the Jews of Greece.4 Katherine Fleming’s 2008 work focuses on the Greek identity of twentieth century community members and their descendants who no longer live in Greece.5 Joshua Plaut’s book which accompanied an exhibit of the same name looked briefly at the history and present-day circumstances of Jews in the Greek provinces.6 He categorized these communities as rural, although they were primarily located in smaller, urban provincial capitals where they plied their trades as primarily merchants.

Rae Dalven was one of the earliest researchers who wrote in English about the community into which she was born. She was a daughter of Ioannina, raised and educated in New York’s Lower East Side where an outpost was established in the early twentieth century. Dalven was a literary scholar, a translator of the Greek poet Cavafy7 and others. Her groundbreaking book, The Jews of Ioannina,8 and select articles document the history of the community as well as aspects of traditional culture such as marriage, naming, and the annual cycle.

Another native who wrote about the community of his birth is Dr. Michael Matsas.9 His book, The Illusion of Safety, presents the complex story of Greek Jewry, especially the Romaniotes, during the Second World War. After a section focusing on the complex history of the war in Greece he writes about individuals and their experiences during the war. He includes the saga of his family who spent the time in hiding.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, about half of the Ioannina community left for economic, religious, and other reasons. The largest number of immigrants settled on New York’s Lower East Side. There, they founded the Broom Street Synagogue, formally known as Kehila Kedosha Janina (KKJ)10. This historic site remains an active synagogue and houses a small museum. Under their direction, a small memorial book was compiled. Here, the victims of the Nazis are listed along with family members and other information.11

My own book, We Are Few, Folklore and Ethnic Identity of the Jewish Community of Ioannina,12 is an in-depth ethnography of the community in the 1980s. Based on extensive field work in Ioannina along with archival work, this study compares traditional culture in the past when the community flourished with that which survived the ravages of the Holocaust to show the persistence of Greek-Jewish identity.

Several Greek Jewish authors have written in Greek about different aspects of the Jewish community in general and Ioannina specifically. Asher Moissis married into an elite family of Ioannina.13 His writing in French and Greek generally addresses the history and culture of the Jews of Greece while also addressing Ioannina as it stood out among the Sephardic communities.14 Joseph Matsas15 was a teacher, turned businessman who loved the community into which he was born. He contributed a number of articles about features of the cultural heritage of the community, including songs and poetry, naming traditions, and the synagogue.16 Eftychia Nahman wrote a delightful memoir of the city of her family.17 She and her family survived the war in hiding in Athens. Her book touches on the life of the community just before World War II and the efforts of the survivors to rebuild their lives.

The following looks at three books and one movie about the Jewish community of Ioannina, released between 2003 and 2019. First is a linguistic study of Judeo-Greek, the little documented language used by members of the community. Next is an all-too-brief, yet significant memoir of a woman who grew up in Ioannina and returned after imprisonment in Auschwitz. A heavily annotated collection of photographs from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is an outstanding record of the life of an affluent family in the community as well as of the city itself. Finally, a documentary film delves into the history and culture of the unique Jewish community. Through the last two works, Ioannina comes to life visually.

Mary C. Connerty

Judeo-Greek, The Language, The Culture

New York: Jay Street Publications, 2003, ISBN: 1889534889

Linguist Mary C. Connerty had two goals in this thin volume. First, she describes the linguistic features of Judeo-Greek focusing on phonological, morpho-syntactic, and lexical characteristics. Second, she examines the current status of Judeo-Greek with reference to now dated research to document the process of language death. Connerty, who holds a master’s degree in linguistics from the University of Pittsburgh, brings her knowledge of linguistics to this brief, yet rich study. Much of her data was drawn from field research in New York City and Israel and phone interviews with individuals in Greece, whom she calls native speakers of Judeo-Greek. The extensive questionnaire that she used and words elicited from her consultants are provided in appendices at the end of the book.

The book begins with a brief background to the Greek-speaking Jews and the status of research into Judeo-Greek. Connerty concludes here that a “thorough description of linguistic features” (p. 18) of Judeo-Greek is lacking because of a paucity of research. She also describes her methodology along with demographics of the individuals whom she interviewed.

In Chapter 2, she provides an introduction to the notion of Jewish languages. A history of the Jewish community of Ioannina, which remained the primary location where Greek-speaking Jews lived into the twentieth century, is given along with background about the religious and cultural life of the community. She writes about the origins and development of Judeo-Greek, a language which “has been known to exist from medieval times onward …” (p. 40). In addition, she provides an introduction to Judeo-Greek references and the influence of Greek folk culture, in hymns, songs, and poems although stating that “not much written work in [Judeo-Greek] has been collected.” (44)

The linguistic features and a thorough, technical linguistic analysis of Judeo-Greek is the focus of Chapter 3, especially features which are distinct from the demotic Greek spoken in Epirus, the region of which Ioannina is the capital. Connerty traces non-Greek loan words found in Judeo- Greek, as they also appear in other Jewish languages. Examples she provides come from Hebrew, Arabic (via Turkish), Italian, French, Ladino, and Turkish. She also uses numerous examples to discuss phonological, semantic, and syntactic characteristics of the language in great depth.

The topics of the next two chapters are the early twentieth century status of Judeo-Greek and the death of Judeo-Greek. She discusses the steps to language death in general as well as in association with Judeo-Greek. Connerty concludes that she feels that she has reached a goal to “help to preserve knowledge” of Judeo-Greek.18

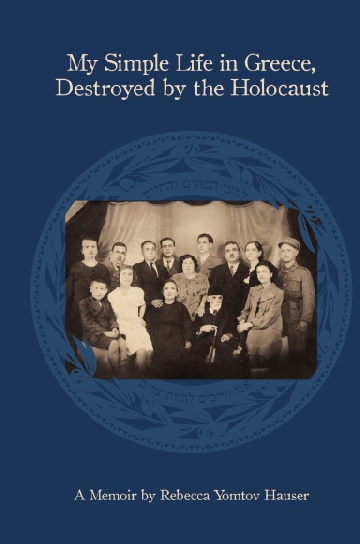

Rebecca Yomtov Hauser

My Simple Life in Greece, Destroyed by the Holocaust

Morrisville, ND: Lulu Press, Inc., 2012, ISBN: 9781312187528

After many years of painful silence, Rebecca Yomtov Hauser finally decided to capture her life experiences in an all-too-brief memoir. She documents her life as a child in Ioannina and her experiences as a Holocaust survivor. Through her writing, images of a life in this city along the lake are created. That life was abruptly dislocated with the entrance of German soldiers during the final years of World War II.

Hauser’s early memories in general include those associated with activities along the ever present lakeside, or molos, and the nearby platia, about fish brought by fishermen from the lake, and excursions across the lake to [D]Rabatova for picnics. Next follow recollections of Jewish holidays and the synagogues in the city; her family attended what she calls the larger of two synagogues in the city. A photograph of the Yomtov home is located in a neighborhood near what was known as the “Outside” synagogue. Brief descriptions are provided of the celebrations of the annual holiday cycle starting with Rosh Hashanah through Shavuoth. She briefly describes distinctions between male and female customs. Passover is the only holiday discussed in any detail, especially the extensive preparations for the eight-day festival. This chapter closes with an whiff of regret at not recalling more.

Hauser next writes about her family. Her mother’s family was Sephardic from Castoria; I wondered how her parents had met or been matched, as was the custom. Part of her narrative explains the naming traditions followed in the Jewish community of Ioannina, which she continued with her own children. Other traditions she mentions in the narrative of her family include the Christian woman who lit the fire on the Sabbath; the Jews of Ioannina followed traditional practices. This chapter is illustrated with evocative photographs, several of which show stiffly posed groups in the photographer’s studio.

Two of her paternal uncles and one maternal uncle had immigrated to the United States sometime between the wars. The family celebrated “special times” when they made return visits to Greece. She recalls three such times. I imagine the pre-war family photos included in the book had been sent to these overseas relatives. Hauser also recalls good times and bad times during her childhood, including incidences of family illnesses.

Rebecca Yomtov and brother Isaak, 1912 in Ioannina Courtesy of the Kehila Kedosha Janina.

The peaceful life in Ioannina was disrupted by World War II. First came the Italians. Her brothers had already done their military service; they were called up to serve again in the Greek army’s fight against Italy. Next, the Germans came and her life and that of the Jewish community changed forever.

Hauser’s memories of the Holocaust start with the transport of community members across Greece and eventually to Auschwitz just before Passover. She vividly captures the sense of disbelief and unreality felt by fellow community members. In the following accounts, the author traces her experiences, what she observed, and the meager life as a prisoner in Auschwitz. She eloquently puts the unbelievable that we are all familiar with into words.

“After showers, there was a table with jackets. We took our dresses and underwear and stayed in line to get a jacket. When I was the next one in line … they handed me the one on top. It was more like a shirt than a jacket. Pitifully I looked down to see that ugly little shirt. Tears came to my eyes. Dumb luck…I thought” (pp. 31-32).

A year and several lifetimes later, she is liberated. Routed with several other Greek survivors through Brussels, Hauser finally reaches Ioannina. Slowly, a few relatives return from hiding and from the camps. She learns from one about the fates of her brothers who were also transported to Auschwitz and did not survive.

Eventually, Hauser is connected with her extended family and relocates to Athens. From there, contact was made with her family in the United States; they send the requisite support for her to join them. Given a choice, she travels by ship rather than plane. Upon arrival she is met by cousins who take her to the family in the Bronx. What follows are memories of a new life in a new country, including how she met and married her husband.

Hauser’s quiet sense of humor and love of life shines through this all-too-brief sequence of memories of her life. She closes the book with the words “Staying positive helped me” (p 51). I characterize this narrative as a beautifully-written collection of kernels, of short snapshots of a life and people remembered through the veil of a tragedy no one could have conceived of. It is yet another glimpse into the life of the Jewish community of Ioannina.

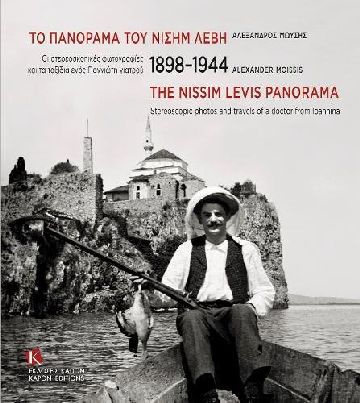

Alexander Moissis

1898-1944 The Nissim Levis Panorama:

Stereoscopic Photos and Travels of a Doctor from Ioannina

Athens: Kapon Editions; English, Greek, 2016, ISBN-10: 6185209128

The Nissim Levis Panorama is a rich contribution to the story of the Jewish community of Ioannina. It was thoughtfully compiled by a descendant of one of the most noted families at the height of the community. Davidson Effendi Levis was a man whose life spanned two centuries from the close of the Ottoman Empire through the birth of the modern Greek nation. He was one of only a few Jews who served in the 1877 Ottoman parliament. His educated sons chose to live in different European cities where they carried on the successful family businesses. One son, Nissim, returned to his hometown to work as a doctor after he studied in Switzerland and interned in Paris. Nissim was a lover of automobiles and photography. This coffee-table-like volume is only a selection of photographs he took of his family and their life, his city, and more, and through it, a window is opened into a life that has not been well documented.

The noted historian of Greek Jewry, Mark Mazower, points out in the Prologue that Nissim Levis’ photographs document a segment of European bourgeois society, in this case from a geographically remote part of Europe, the northeastern corner of Greece. And yet, this Jewish community was neither economically nor intellectually isolated; business and family associations were built across the continent. Mazower also emphasizes that Levis’ unique collection of photographs serves as a roadmap through a complex maze of history from the 1890s to the Second World War. They provide a social context to the full life in which the photographer and his extended family lived.

The Introduction and text accompanying the photographs is written by Alexander Moissis. His grandfather was Asher Moissis (mentioned above), a writer, translator, and leader of the post-World War II Jewish community of Greece. The elder Moissis was married to a great granddaughter of Davidson Effendi. Alexander writes about how the family discovered Nissim’s stereoscopic photographs by chance on a return visit to Ioannina shortly after the war. A street vendor was selling views of the old-time panoramas which his grandmother recognized as family heirlooms. They were able to purchase the glass plates and thus save them. He refers to them as the family legacy; they are much more, a chronicle of a significant Jewish community over a span of more than fifty years.

The process of organizing the images that capture four generations about whom knowledge had been lost is detailed in the Introduction. Moissis also describes the detective work he undertook to identify locations and dates of the photographs and name the individuals inhabiting them. Features such as long-gone minarets, trees, and clothing helped to date many images. This attention to detail provides historical context and enriches the information accompanying each photograph in the book.

The photographs in The Nissim Levis Panorama are organized in six sections which consist of overlapping time periods. Readers are taken from everyday life in Ioannina in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to a period of political upheaval in the second decade of the twentieth century. Other sections document travel, either Nissim’s travels during his time as a medical intern in Paris or family excursions after the First World War. The book concludes on a grim note of March 25, 1944, when community members were deported for the long journey to Auschwitz.

Part One focuses on life in Ioannina between 1898 and 1912. Readers are introduced to the Levis family and the two adjacent Levis mansions on Odos Koundouriotou, with street views and views of the gardens and the house interiors. The patriarch, Davidson Effendi, is shown in his splendor, medals and all for his service to the Greek nation and the Ottoman sultan. Significant about these particular images is the relationship between the leadership of the Jewish, Orthodox Christian, and Muslim communities, a theme mentioned repeatedly in the film Romaniotes (see below). This camaraderie is evident in outings on Lake Pamvotis captured in the photographs. A few other images document family life cycle events including the dowry, engagement, and wedding events and, subsequently, the growth of the large Levis family.

Political change in Ioannina is documented in Part Two as the city moved from being an Ottoman provincial capital to being integrated into the new Greek state. Again, the inter-ethnic relationships between community dignitaries and government officials are visually represented. Other images show aspects of the approaching First Balkan War in 1912 including troops marching through the center of the city. The section closes with the return to normalcy and social outings of the family and others.

Part Three includes photographs that document twenty years of travels by the family by carriage, on horseback with a pack animal convoy, and by automobile. Some family journeys were simply for recreation to favorite locales in the countryside around Ioannina. The landscapes of a time past illustrate the raw beauty of this region of Greece. Other travels follow the road to the Adriatic coast and to Corfu. There, the family took a boat to Brindisi and travel continued on the European continent. Levis’ photographs capture many scenes of the ports through which they entered, including Genoa, Naples, and Marseilles in the early twentieth century.

Two sections document different periods of Nissim’s five years in Paris. Part Four captures the life he led in the city while an intern at the Trousseau Children’s Hospital. The emphasis of these images is upon his extracurricular student life rather than his work. Several photographs are of student costume balls and gatherings at Café Soufflet and nearby Luxembourg Garden, which he frequented. Numerous scenes documenting the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris, including many of the national pavilions, close this part of the book.

Part Five contains many views of travel in Europe enjoyed by Levis and fellow interns. Marseille and Nancy were two destinations because family members lived there. These photographs provide interesting images of bourgeois home interiors and décor. The photographs of several summer treks to the Pyrenees are breathtaking. Of course, automobile travel was still new in 1901 and a number of images document the dilemmas faced when the car broke down. Also included are images of trips to Asia Minor in the first decade of the twentieth century, including historic sites in Greece, Istanbul, and Izmir. The final section of the book returns to Ioannina and numerous excursions the family took between the wars. As a family of means, they enjoyed trips to Paris, Switzerland, Milan, and Venice, as well as Athens. The book closes with the only photograph that was not taken by Nissim Levis. It is an anonymous photo recording the drama of the deportation of members of the Jewish community in March 1944.

As a rich document of a time filled with rapid changes, The Nissim Levis Panorama records moments in the life of the Levis family. Before the present day of selfies, this was a family which liked photographs of themselves, perhaps to send to relatives no longer living in their hometown, Ioannina. Carefully observing the images one can follow the fashions of the day. Women’s hemlines rise and their pinched waists are relaxed. Men’s hat styles change and Ottoman fezzes are exchanged for homburgs.

Levis’ photographs not only record the history of his family, but also a Jewish community and the city in which they were lived. Images are accompanied with thoughtfully worded and informative text. As already mentioned, through meticulous research, topical information is provided about the Levis family; the individuals populating the photographs and their relationships are carefully described. Historic information also complements many of the photos. In addition, present-day images are frequently juxtaposed with the historic ones to allow readers to see and compare same location or building, a century later. Curiously, the early twentieth century photographs of the city’s market place, except for the cobblestone paving, look almost the same as they did in the 1980s.

One of the most difficult tasks of publishing is catching typographical errors and inconsistencies in the text. While this does not take away from the significance of the work, here they tend to be a minor annoyance to the reader. In addition, the book would have benefited from a map to aid readers who are unfamiliar with the northwestern corner of Greece and names of unknown villages.

The Nissim Levis Panorama comes full circle. It is a book of photographs assembled by the grandson of Asher Moissis, one of the scholars who wrote about this community, and who married into the family in 1928. It is the labor of love of a great grandson of the patriarch, Davidson Levis and a descendant of the remarkable Jewish community of Ioannina.

Romaniotes, 2019

Directed by Stylianos Tatakis

67 minutes. In Greek with English subtitles.

Romaniotes is an in-depth, emotional introduction to the history and culture of the Jewish community of Ioannina. The multiple voices heard in the film include a number of community members and descendants.19 Foremost is Moses Eliasaf, president of the community and professor of medicine at the University of Ioannina. In 2019, Eliasaf was the first Jew elected mayor of a Greek city. Other speakers include Raphael Moissis and his son, Alexander Moissis. They are descendants of the legendary Davidson Effendis Levis, a community leader at the close of the Ottoman period (see above).

The film moves from topic to topic to relate the multi-faceted story of the Greek-speaking Jews who long pre-dated the incursion of Sephardim who left the Iberian Peninsula under force. In fact, the origins of this deeply rooted community are unknown as viewers learn, but it is indisputably among the oldest in Europe. In most other locations in Ottoman Greece, the Romaniote or Greek-speaking Jews acculturated to the more numerous Judeo-Spanish Jews. Not so in Ioannina and several other, smaller cities. According to Dr. Leda Papastefaniaki, professor of history at the University of Ioannina, Romaniote communities are distinguished by language, religious rites, and their geographic environment. The latter is certainly the case of Ioannina, capital of the region of Epirus, located on a peninsula in Lake Pamvotis, surrounded by mountains. She also considers this to be the least studied Jewish community in Greece.

A catalog of customs and traditions are interwoven into the history of the community in the film. The Ottoman period leads to integration into the Greek state, then to the devastation of the Holocaust and its aftermath. Historic images of the city by Edward Lear and others, historic photos including many taken by a member of the Levis family (see above), and impressionistic aerial shots of the wintry city by the lake illustrate the narrative.

Among the customs mentioned that are unique to Ioannina are alefs, richly illustrated certificates filled with blessings for newborn baby boys. Silver shadayot, or dedication plaques/amulets, which are donated to the synagogue for a number of reasons are another item addressed. These are more or less ex votos, similar in use though not in form to those found in the Greek Orthodox churches. Another similar custom and object in both churches and synagogues is the kandiles, or oil burning lamps. On the day preceding Kippur, they are cleaned and decorated with flowers by children in the community.

A significant thread repeated frequently throughout the film is the close relationship between Jews, Christians, and Muslims since the Ottoman period. A historic photo of an Ottoman mayor, Yaya Bey, with Davidson Effendi Levis and Constantine Sourlas, a Greek-Christian member of the Ottoman parliament, on a hunting trip exemplifies this point. Several speakers address the interconnected situation, making it a centerpiece reiterated in the film.

Emphasis is placed on the fate of the community during World War II. Local journalist/researcher, Alekos Raptis, explains how a small group of previously unknown photographs taken on the day of deportation were found recently in an Austrian archive. Several voices tell of their experiences or the experiences of their families. Stella Cohen, who survived Auschwitz with her sister, Eftichia, shares her bittersweet recollections.

The story of Davidson Effendi Levis is a constant thread through the entire film. These images are those taken by Nissim Levis. Moissis’ father remembers that in his youth, the children were distracted with the heirloom stereopticon or “appareil” and slides of Ioannina and places in Europe.

In several instances, the scene is supported with poems by the noted Jewish poet Joseph Eligia,20 a native of Ioannina. “Nostalgia” is presented with a background of photos of early twentieth century immigrants to New York. Their continued yet distant connection to their homeland is implied. The film ends with the poem “Pamvoti,” the lake in the background of the everyday life of all who lived in Ioannina. I wished that the filmmakers had provided information about this native son.

Romaniotes addresses many topics about a historic European Jewish community that is shrinking, if not dying. Through the voices of community members and others, viewers learn about its history and tidbits of unique cultural practices of the past. Along with the many romantic shots of the city, the film takes viewers on a very special and well-documented journey into the past of a unique community.

Much remains to be written about the Jews of Ioannina and the other, smaller Romaniote communities. History, rabbinic responsa, and traditional culture are topics that can be further documented. Research can be conducted with descendants of the community in Ioannina, Athens and other cities in Greece, Israel, and the United States. One day at work a number of years ago, I greeted visitors to the museum. They were from Venezuela. I asked their names; one had a typical Ioannina Jewish family name. Surprised, he shared that, yes, his family had immigrated from Ioannina to Caracas in the early twentieth century. This essay is lacking explorations of publications in languages other than English and Greek. Perhaps another generation of scholars can correct this and fill in the blanks to understand this ancient and rich community

1 Annette B. Fromm, is a folklorist and lecturer in Romaniote Sephardic studies.

2 Zanet Battinou, ed., Corpus Inscriptionum Judaicarum Graeciae, Corpus of Jewish and Hebrew Inscriptions from Mainland and Island Greece, (Athens: The Jewish Museum of Greece, 2018).

3 Yedida K. Stillman and Norman A. Stillman, eds., From Iberia to Diaspora: Studies in Sephardic History and Culture, (Leiden: Brill, 1999), George K. Zucker, ed., Sephardic Identity: Essays on a Vanishing Jewish Culture, (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, 2005).

4 Steven Bowman, The Agony of Greek Jews, 1940–1945, (Stanford, Ca: Stanford University Press, 2009), Steven Bowman, The Jews in Byzantium, 1261-1453 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1974).

5 Katherine Elizabeth Fleming, Greece: A Jewish History, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008).

6 Joshua Plaut, Greek Jewry in the Twentieth Century, 1913-1983: Patterns of Jewish Survival in the Greek Provinces Before and After the Holocaust, (Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1996).

7 Rae Dalven, trans., The Complete Poems of Cavafy, (Boston: Mariner Books, 1976).

8 Rae Dalven, The Jews of Ioannina, (Philadelphia: Cadmus Press, 1990).

9 Michael Matsas, The Illusion of Safety, The Story of the Greek Jews During the Second World War, (New York: Pella Publishing Company, 1997).

10 "Greek Jewish Festival at Kehila Kedosha Janina Synagogue, New York City." Sephardic Horizons, Vol.8, Issue 1-2.

11 Marcia Haddad Iconomopolis, ed., In Memory of the Jewish Community of Ioannina, (New York: Bloch Publishing Company, 2004).

12 Annette B. Fromm, We Are Few, Folklore and Ethnic Identity of the Jewish Community of Ioannina, (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2008).

13 See more about Asher Moissis in the reviews below.

14 Asher Moissis, situation des Communautés juives en Grece, in Les Juifs en Europe (1930-1945), (Paris: Centre de Documentation Juive Contemporaine, 1947): pp. 47-54, Asher Moissis, Elleno-Ioydaikai Meletai (Greek), (Athens: n.p., 1958), Asher Moissis, E Onomatologia ton Evraion tes Ellados (Greek), (Athens. n.p.: 1973).

15 The surname Matsas occurred frequently in Ioannina. The two writers were not related.

16 Joseph Matsas, Yianniotika Evraika Tragoudia (Greek), (Ioannina: Ekdosis Eperotikes Estias, 1953), Joseph Matsas, “Ta Onomata ton Evraion Sta Yiannina” (Greek), in Afieroma es ten Eperon. Eis mnemen Christon Soule 1892-1951, (Athens: n.p. 1955): pp. 95-102, Joseph Matsas, “E Archaia Iera Sinagoge ton Ioanninon” (Greek), Chronika, 1977: 3: 3-5, Joseph Matsas, “Jewish Poetry in Greek” (Hebrew), Sefunot 1971-81, 15:235-266, Joseph Matsas, “E Giorty tou Pourim sta Yiannena” (Greek), Chronika, 1982a: 47:3-4, Joseph Matsas, “Iera Kemena se komike diseve yia to Pourim” (Greek), Chronika, 1982b: 47:5-7.

17 Eftichia Nachman, Yiannina, Taxidi sto Parelthon (Greek), (Athens: Talos Press, 1996). This book was published in English as Yannina: a journey to the past, (New York: Bloch Publishing Company, 2004).

18 Since Connerty wrote her book in 2003, more research has been conducted into and written about Judeo-Greek. Notable is the work of Julia G. Krivoruchko, see “Judeo-Greek,” in Handbook of Jewish Languages, 2016, 194–225 and “Judeo-Greek in the Era of Globalization,” Language & Communication, 31, 2, May 2011: 119-129.

19 I, too, am a descendant of Ioannina. My maternal grandparents (Joseph and Esther Bacola, née Cohen) immigrated to New York City in the early twentieth century where they met and married and raised a family.

20 Rae Dalven also translated Eligia’s poems from Greek to English, see Poems, translated from the Greek (New York, Anatolia Press, 1944).

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800