Cara Judea Alhadeff, Micaela Amato Amateau, Illustrator

Zazu Dreams: Between the Scarab and the Dung Beetle:

A Cautionary Fable for the Anthropocene Era

Lemont, Pa: Eifrig Publishing, 2017, ISBN 978-1632331182

Reviewed by Sajay Samuel*

Dreaming of Home

“There is something peculiar about this book: the fact is the cover gives it away right from the start.” That was the first line of Walter Benjamin’s review of The Fairy Tale and the Present written by Alois Jalkotzy in 1930. Benjamin excoriated that author for diluting the fairy tale, once replete with evil step-mothers, murderers, and drunks, into a saleable commodity made of bland pieties suited for “children.”

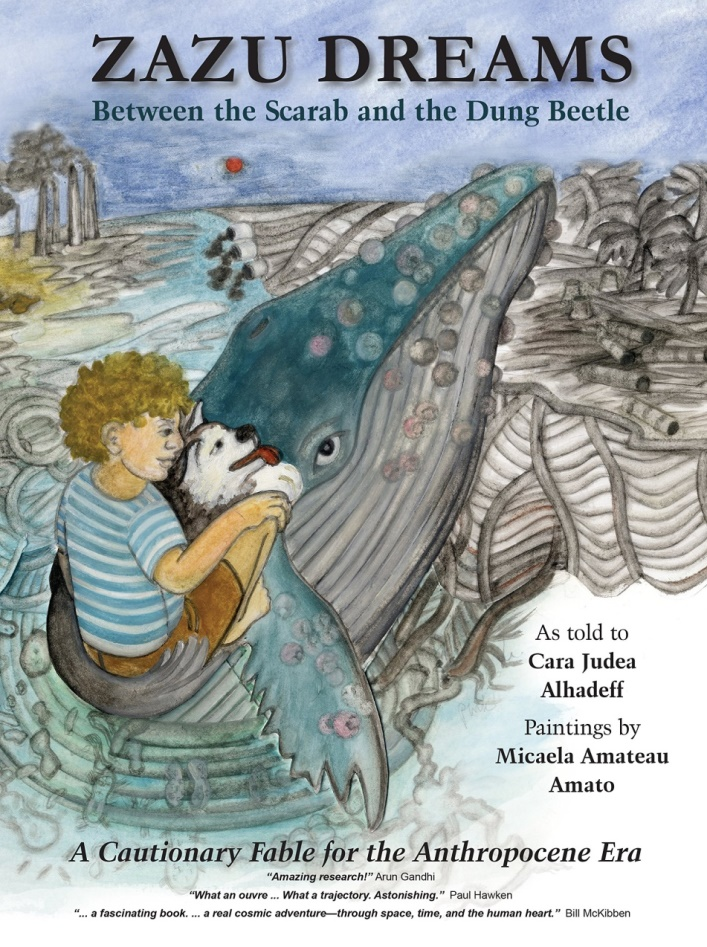

No such charge can be made against Zazu Dreams. Its cover pulls no punches. In the foreground, a young man, Zazu, holds his malamute husky, Cocomiso, atop their friend, a humpback whale. In the background is a tableau of the contemporary grotesque. On the right, sewers vomit effluent into the sea. On the left, chimneys belch noxious fumes into the night air. Between these man-made geysers, a red moon hangs: low, fat, ominous. Zazu Dreams is not for the helicoptered and the coddled, those sensitive to micro-aggressions and in need of trigger warnings. Zazu Dreams is an unvarnished fairy tale in which the comforting is enfolded within the scary and the beautiful is braided into the ugly. Zazu dreams in images, in words, in philosophical musings, and in historical forays. Zazu dreams to awaken us from our slumbers.

Boy, dog, and whale traverse oceans, crisscross centuries, now fly towards the sky, now dive into the ocean deep. They travel to the ends of the earth, searching and searching, without rest. What is it young Zazu searches for? He searches for home, for being-in-place. Zazu seeks to be one among other beings, whether these be trees, animals, waters or skies. But wherever he goes all Zazu finds is the overweening presence of the human being. Of human things that engorge on the suffocation, mutilation and destruction of all other beings, including other humans, Zazu searches for home because he has been made homeless. But why the restlessness? Zazu is restless because he can find no place to rest, because the earthbound, the terrestrial, has been exiled from the earth.

Today, the prime mover of this displacement is the corporation. Corporations have exiled the terrestrial and now squat over the whole earth. Despite its name which invokes the dense materiality of flesh and earth — corpus, corporeal, corpse — the corporation is, in fact, an extra-terrestrial. Once a legal fiction invented by some humans, it now rules over human and other beings as an amortal Demon-God. The expanding universe of corporate fictions already owns the earth, the seas, and the skies. Even the wind and the sun now fall within the grasp of private and state corporations. And all that the corporation touches it remakes in its own image. Land and water and air, birds and fish and fowl, all these and more have been fictionalized into resources. Nothing seems able to escape the insatiable vortex of this fictional pair, “corporation/resource.” As Zazu discovers, even primordial sustenance, mother’s milk, has been mined for its ingredients to be packaged for profit.

Amortal corporations are a phantasm just as fairy tales are a fantasy. The corporation cannot be held guilty any more than a fairy tale can be put in the dock. Rewriting fantasies will not make them less fantastic. A tasteless story is best just not told. Corporate minions cannot be punished any more than robots can be jailed. Both are critters who willingly enact what others have willed, who only do their jobs! Reprogramming machines will not alter their inability to disobey. A mindless robot is best turned off. But everywhere Zazu goes and everywhere Zazu looks, all he can see is the detritus of corporations and its efficient executors. The rule of the corporate form seems unassailable, its power absolute, its malefic consequences unavoidable. Are we therefore condemned to serve the monsters we created?

Fruits take their time to ripen. I had to wait a year to write this appreciation. I wanted to find out what happened to the Jewish community of Cochin whom Zazu discovered there during his travels. My parents once lived in the neighborhood of the famed Jew-town of Fort Cochin, Kerala. They knew of the Koders, Sattu, brother Elias, sister Lily, the preeminent family among the “white” Jews of Cochin. Until the mid-1980s, there were enough members to constitute the minimum ten persons needed for synagogue services. In 1987, an unbroken four hundred and nineteen years of Shabbat minyan came to an end for the lack of quorum. Now there are said to be but five Jewish persons left in Jew-town. Rumor has some three or four “black” Jewish families are living on the mainland, though not much more is known of them. Such are the tatters left of the once vibrant fabric of Kerala Jewry.1 Such withered remains of community are witness to our contemporary condition. Must we therefore resign ourselves to cynicism and despair?

Zazu grows up among people who speak Ladino, a linguistic mosaic that began as the Spanish spoken by Jews in medieval Spain. Enriched by exilic wanderings since 1492, Ladino absorbed elements from Greek, Turkish, Hebrew, Arabic, French and more. Its continued, if fragile existence, gives voice to the power of enfleshed words, of embodied speech, of the irrepressible murmur of voices that always threaten the rule of grammarians. Zazu’s vernacular signposts the fate of those unhoused, uprooted, cast adrift. For is it not speech that forms the bubbling ground from which an “I” separates itself from a “we,” a “we” that is stutteringly convoked prior to the collectives of family, tribe, society, nation, and even species? The variety of voices may well be countless: the scream of monkeys tortured to test shampoo, the moans of a grieving father, the mating songs of humpback whales, the laughter of a child at play. And yet, perhaps, it is precisely in this tyrannical anarchy of voices that the restless might find home.2 The word is tyrannical because it cannot be escaped. The word is anarchic because it has no author. Perhaps the anarchic tyranny of speech does bind those who have little in common, as it does for Zazu and his friends. Perhaps Zazu’s dream for us is also to seek home in vernacular activities, vernaculars that endlessly express the endlessly inventive capacity of humans, to be.

Zazu Dreams in the teeth of despair, searching for redemption in shit. That he still dreams is a sign of hope emergent, of the green shoots of spring. By dreaming with Zazu one may learn how to live in the ruins, amid the irreparable, among the fallen.

Ed. note: The author Cara Judea Alhadeff's web page is accessible at http://www.carajudea.com/.

* Sajay Samuel is Clinical Professor of Accounting at The Pennsylvania State University. He teaches how to commensurate unlike things through the techniques of accounting. He studies/researches the improprieties of doing so. Recently, he shepherded into print a book of essays by Ivan Illich, whose lucid, if sober diagnosis of the contemporary predicament points to the world Beyond Economics and Ecology (London: Marion Boyars, 2013)

1 Nathan Katz and Ellen Goldberg carefully document the history and fortunes of the Cochin Jews in The Last Jews of Cochin: Jewish Identity in Hindu India (University of South Carolina Press, 1993). Shalva Weil offers a thorough if brief survey of “Jews in India” in the Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora, v.3, ed. Avrum Ehrlich (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2008, pp.1204-1212). For a tender and bracing personal account of homelessness read the remembrances of Ruby of Cochin: an Indian Jewish Woman Remembers by Ruby Daniel and Barbara Johnson (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1995).

2 Resounding through Alhadeff’s “search for home through language” is George Steiner’s “Our Homeland, the Text” reprinted in his collection on reading and writing titled No Passion Spent (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995).