Film Review

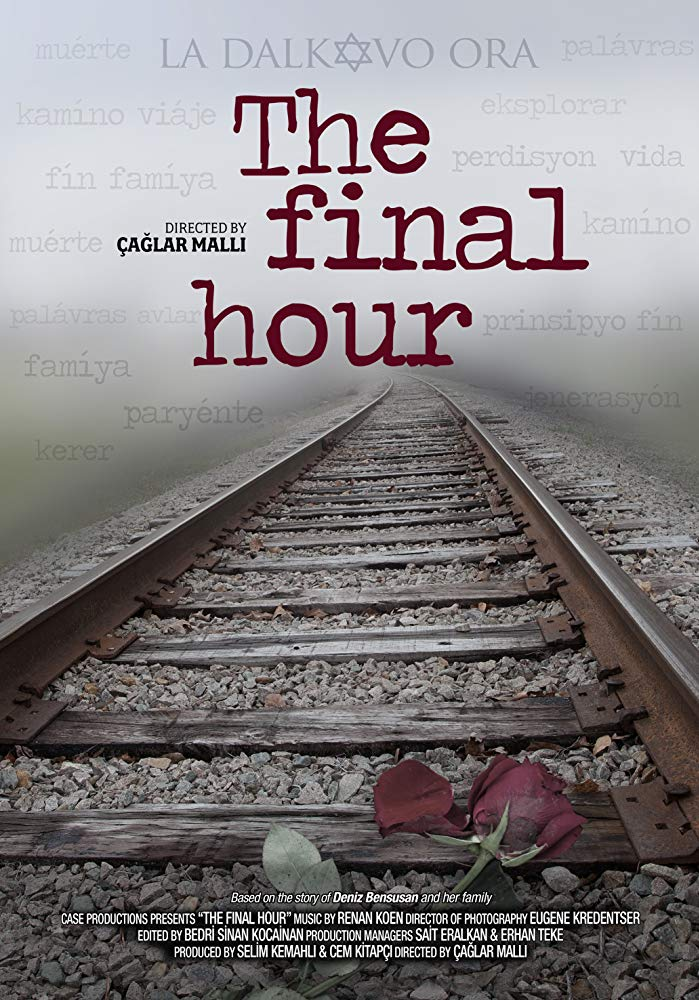

THE FINAL HOUR, 2019

Directed by Çağlar Mallı

88 minutes. In English, Spanish, Turkish, Portuguese with English subtitles

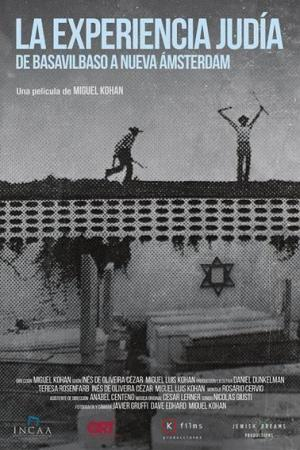

The Jewish Experience, from Basavilaso to New Amsterdam, 2019

Directed by Miguel Kohan

88 minutes. In Spanish and with English subtitles

Reviewed by Annette B. Fromm*

Two documentaries of Sephardic interest were among a large selection of films shown at Miami Jewish Film Festival in January (https://miamijewishfilmfestival.org/films/2020/). These two films were North American premieres, as were several others included in the heavy 2020 Film Festival schedule. The directors and/or producers of both films were present for the showings to briefly introduce their films and field questions following the showings.

The two seemingly unrelated films document journeys of discovery of history and identity in several areas where exiles from the Iberian expulsions settled five hundred years ago. The Final Hour follows a young Turkish-Jewish woman who travels from Istanbul to Greece, to Auschwitz, and finally to Portugal and Spain. In the case of The Jewish Experience, the director explores the stories of several defunct and extant communities that represent the Portuguese Nation in the Caribbean and South America.

The Final Hour introduces Deniz Bensusan, a young woman who grew up in a loving Sephardic family in Istanbul. The film documents Deniz’s exploration to find and learn about the heritage of her family, with some emphasis on Ladino (Judeo-Spanish), the language her grandparents spoke. The primary question posed repeatedly at the beginning of The Final Hour is whether Ladino, the language of the Sephardic Jews in the Eastern Mediterranean, is dead or dying? Why didn’t her Turkish grandparents teach or speak with her and her parents in Ladino? Also explored is whether the culture which utilizes a language perishes when the language also dies? These questions propel her on a voyage of discovery as she attempts to unearth her culture, language, and roots.

In Istanbul, viewers are introduced to Deniz’s family including her maternal grandparents, mother, and Renan Koen, a cousin and musician who also wrote the score for the film. The filmmakers visit a number of experts and community members who voice their opinions about the intertwined nature of language and culture. Included are the chief rabbi, or haham bashi, of Turkey; Naim Güleryüz, a leading force of the 1992 Quincentennial commemorations of the expulsions; Karen Gerson Sarhon, founder and director of the Istanbul-based Ottoman-Turkish Sephardic Culture Research Center and promoter of Ladino studies; among others.

Deniz’s journey takes her on an emotional roller coaster as she traces her family and meets the small surviving communities of Sephardic Jews in Salonika and Kastoria, where much of the Bensusan family lived prior to World War II. Her grandmother has already explained that because some of the family moved to Edirne in Turkey, not everyone was lost in the World War II concentration camps.

Her next destination is Auschwitz to try to understand the agony of her family’s final days. It is also in Auschwitz with the mass extermination of the Jews of Salonika that Sephardic culture including Ladino was largely eliminated. Here, she posits that the “final hour” of Ladino and Sephardic culture is quickly approaching and realizes that she herself could represent the final generation witnessing the disappearance of her ancestral language.

She continues to a number of locales in the Iberian Peninsula to see from where her ancestors left over five hundred years ago. In Portugal, especially in Belmonte her focus is on the crypto- Jews and how they retained aspects of their long ago Jewish culture. Along the way, she finds long-lost cousins, views the actual Spanish Edict of Expulsion, and encounters many surprises. The Final Hour depicts the centuries-long journey of Sephardic culture and the Ladino language, asking all the while: will it survive another generation? This beautiful film transports viewers from many of the sights and sounds of Istanbul and the Balkans to Portugal and Spain in the West.

Deniz states several times that she is seeking the roots of her family, her heritage, and her identity as a Sephardic Jewish person. At the heart of the adventure, as she calls it, is a discussion of the situation of Ladino in her world and the role language plays in culture.

In The Jewish Experience, filmmaker Miguel Kohan attempts to build connections between the experiences of his Jewish creole family in rural Argentina (Jewish gauchos) with the Sephardic dispersions to the Western Hemisphere from Spain and Portugal which originated in 1492. His personal pilgrimage was guided by the writing of Mordechai Arbell, a self-taught historian of Jews of Caribbean, who is introduced early in the film. Arbell was the consul of Israel in Bogota, Colombia and the Israeli Ambassador to Panama and Haiti. There, he learned of the long Jewish histories in the areas. Afterwards, Arbell researched, wrote, and spoke extensively about the history of the Jews in South America and the Caribbean.

Kohan’s exploration takes him upriver to the jungle in Surinam to reveal the remains of abandoned synagogues and cemeteries of the Jodensavanne (Dutch for “Jewish savannah”) and to the former Dutch island St. Eustatius in the Caribbean. At the former, viewers are introduced to the leader of a group of indigenous people who are self-appointed caretakers of the ruins. At the latter, Kohan learns the story of the vital assistance Sephardic Jewish merchants there provided the rebellious British colony later known as the United States of America. In these locales he finds that, like his own ancestors, Jews who settled in these remote places turned their exile into strength; they learned to coexist and even thrive among the locals.

Next, Kohan travels to New Amsterdam (New York), Jamaica, and Recife (Brazil). His specific goal in New York, the site of the earliest settlement of Sephardic Jews in what became the United States, was to introduce American architect, Rachel Frankl, a driving force of the initiative to identify and save Jewish cemeteries in Jamaica. The cameras in Jamaica focus on work cleaning at several of the twenty-one Jewish cemeteries there. At the screening when asked about filming where people were buried rather than capturing active community life, he expressed the desire to document the preservation of more cemeteries. Visits in Recife are with individuals whose families trace themselves to converso ancestors. The narrative is from descendants of New Christians, individuals who simply recognize their history and some aspects of heritage and others who are returning to Judaism. In the presentation following the film Kohan spoke briefly about how at least one person in the film came uninvited to the filmmakers to share his story after learning what they were doing.

Both films take viewers on voyages of discovery which continue to unfold. They share an impressionistic style that includes long, thoughtful shots of vistas and landscapes. Viewers meander, often silently, from location to location. The films are soulful, thought-provoking portrayals of different voices and opinions about the state of Ladino in Turkey, the history of the Iberian expulsions, and visual introductions to the far flung, but not isolated, small outposts in the Caribbean area.

Storytellers, filmmakers here, face challenges of what to include and what not to include, especially in stories overflowing with content such as these. Decisions related to storytelling might also dilute the narrative. While in Spain, The Final Hour drifts off-base into the realm of inventions targeted at tourists, notably in three instances when scholarship and cultural promotion are mixed. In a Sephardic shop in Toledo, Deniz is shown a carved wooden Madonna figure in which “a fragment from the Torah” (did the speaker mean a mezuzah?) was hidden.1 This object is one of an inventory of “fake” Judaica produced and sold to Jewish tourists seeking to return home with authentic souvenirs. The Director of the Casa de Sepharad in Cordoba speaks and sings emotionally and enthusiastically about the “house of memories” at which the Jewish history in Spain is shared. He stands in front of museum-like display cases filled with a variety of lovely artifacts, the majority of which originated in North Africa, not Iberia. And in Malaga, Deniz visits with an equally passionate Jewish restaurateur who specializes in Sephardic food. Deniz tastes her borekas, which taste like her grandmother’s borekas. She then meets her hostess’s effervescent mother, a Holocaust survivor from Bosnia, probably Sarajevo, now living in Malaga.

The makers of The Jewish Experience faced an expansive geographic area to cover in order to find their stories. Choices had to be made of which communities to include. Thus, Curacao, named the ‘Mother of Jewish communities in the New World,’ is not included. As already stated, emphasis is on the Portuguese nation in the Caribbean. The filming in New York City, however, takes viewers to a neighborhood of men wearing streimls (fur hats) and kittels (black robes) and women modestly dressed with their heads clearly covered with sheitels (wigs). Curiously, the visual stereotypes of clearly Ashkenazi Orthodox Jews are captured. None of these were the dress historically worn in Sephardic communities.

Nevertheless, these two evocative and emotion-laden documentaries, The Final Hour and The Jewish Experience from Basavilaso to New Amsterdam, visually open intriguing vistas of the extended Sephardic world. The former joins a young Turkish Sephardic woman in a journey through history to find the origins of her identity. In the latter, a member of a Romanian Jewish immigrant family that settled in a town in the center region of the province of Entre Ríos, Argentina, seeks similarities between the diaspora story of the first Jews who sought refuge in the Western Hemisphere and that of his family. Both films provide glimpses into the past and the present. They convey emotion-laden, personal stories that will touch and inform all viewers of the amazingly rich and varied history of the Sephardic Jews.

* Annette B. Fromm, is a folklorist and lecturer in Romaniote Sephardic studies. She is also the associate editor of Sephardic Horizons.

1 The Mezuzah in the Madonna's Foot: Marranos and Other Secret Jews--A Woman Discovers Her Spiritual Heritage (1994) by Trudi Alexy is a memoir which has popularized this notion.