The Pleasures of Teaching Ladino

By Gloria J. Ascher*

| Lingua biva sos! Stas biva | You are a living language! You’re alive |

| Oy, akí, entre mozotros, | Here, today, among us, |

| Benadames ke te keren | Human beings who care |

| Tanto! Mira, ya vinimos | So much for you! See, we came |

| A New York, i en Enero, | To New York, in January, |

| I de leshos, sólo para | Some of us from far away, |

| Selebrarte! . . . ”Ya te siento! | Just to celebrate you! . . . “I do hear you! |

| Grasias! Ayde, selebramos!” | Thank you! Let’s get on with celebrating!” |

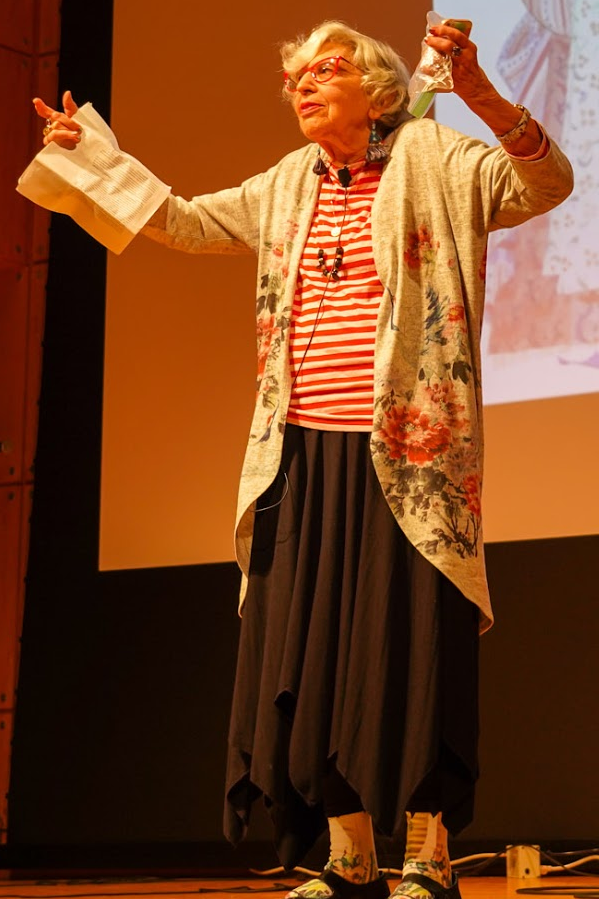

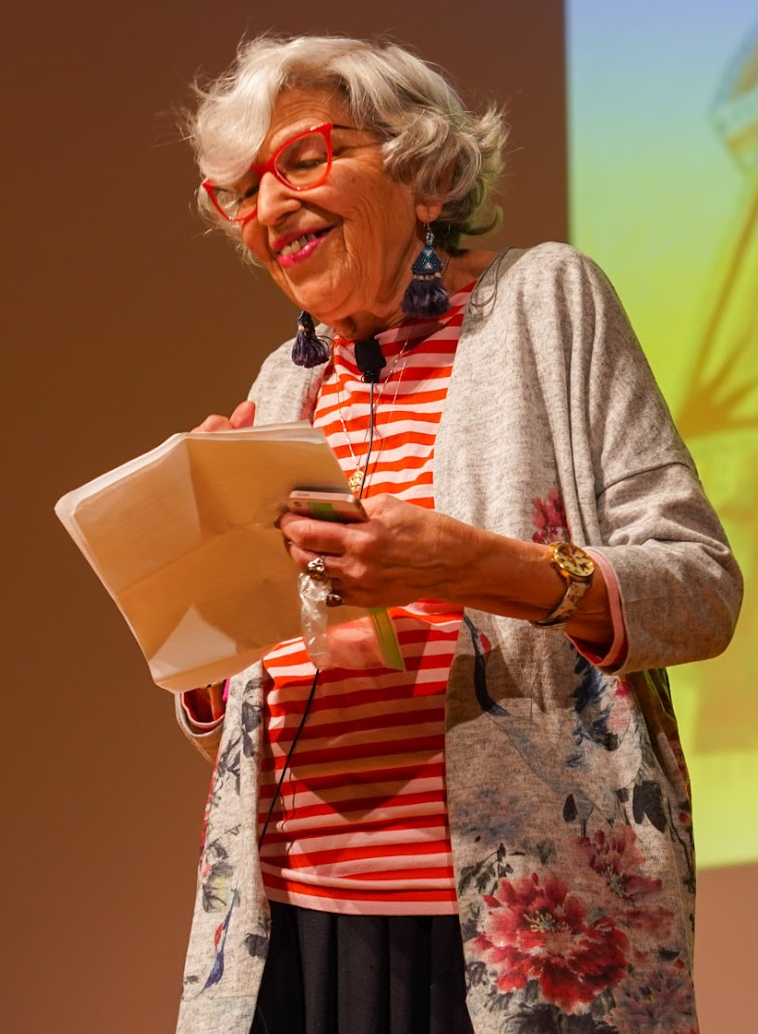

This poem came to me in late

December 2019, as I was anticipating the celebration of International

Ladino Day on January 12, 2020, at the Center for Jewish History in New

York City, at which I had been invited to present by organizer Jane

Mushabac. I recited it there, and I chose it to open this essay, which

is based on my presentation in New York. The poem is, of course, overtly

occasional, linked to the event in New York, which people came from as

far away as Israel to attend. But beyond its ties to that specific

occasion, the poem celebrates the essential nature and attraction of the

living language itself, the source of the many pleasures that teaching

Ladino has brought me.

This poem came to me in late

December 2019, as I was anticipating the celebration of International

Ladino Day on January 12, 2020, at the Center for Jewish History in New

York City, at which I had been invited to present by organizer Jane

Mushabac. I recited it there, and I chose it to open this essay, which

is based on my presentation in New York. The poem is, of course, overtly

occasional, linked to the event in New York, which people came from as

far away as Israel to attend. But beyond its ties to that specific

occasion, the poem celebrates the essential nature and attraction of the

living language itself, the source of the many pleasures that teaching

Ladino has brought me.

In January, I traveled to New York from Hyannis, Massachusetts, but I was also coming home. I was born in the Bronx, New York. My parents, Emanuel and Esther (born Ganon) Ascher, were both Sephardic Jews from Izmir (then Smyrna), Turkey. As their only surviving child, I spent the first twenty years of my life surrounded by relatives and other people whose native language was what we called Spanyol, Spanish, though it is actually a distinct language related to Spanish, and has yet to acquire a universally accepted name.1 I always loved Spanyol. I grew up singing our songs and even collecting proverbs, but I was never allowed to speak the language. My mother, the most patriotic U.S. citizen I know, was so proud that I was born here, and she wanted to make sure I remained “purely American.”

I began composing songs and poems in Ladino years before I taught the language, but it is through teaching that I came to discover, understand, and appreciate its unique qualities and effects. I had already incorporated material on Ladino in my course Aspects of the Sephardic Tradition at Tufts University, and I always had the secret dream of teaching the language. I owe the realization of this dream to my encounter with the incomparable poet, scholar, storyteller, and performer Matilda Koén-Sarano in May 1999. Matilda had come from Jerusalem to Lynn, Massachusetts, to visit her daughter Liora Kelman, who had given birth to a son. A neighbor had shared an article on me in the Boston Globe with Liora, who thought her mother might enjoy meeting someone with a similar background. I was reluctant to meet the great Matilda Koén-Sarano I’ve had bad experiences with famous people, but I couldn’t prevent her from calling me at Tufts. That call was decisive — this was the first time I actually spoke my language! It was liberating, almost surreal. Matilda and I met in person at Liora’s house soon after, and it was instant friendship, something unique in my experience.

After spending that whole day together: sharing a meal, discovering common interests, family artifacts, passions such as writing songs in Ladino, and even life patterns, Matilda said (in Ladino, of course): “You’re a professor at Tufts – why don’t you teach Ladino?” I didn’t really feel I knew the language. “It’s all there within you, and now it just has to come out,” she said. As we say in our folk tales, Ansina fue. That’s how it happened. Matilda’s wonderful Ladino textbook for beginners came out just in time, and, with her help, I translated the Hebrew into English.2

I started teaching my basic

Ladino Language and Culture course in January 2000. In response to

student demand I offered it every semester, except for my sabbaticals,

through Spring 2017, my last teaching semester at Tufts. Ladino was part

of the Program in Judaic Studies and cross-listed with Spanish. I also

offered Ladino continuation courses on request. They ranged from

independent studies with one student to small classes of five to ten

students. Some chose to continue for several semesters (until

graduation!) and even completed Matilda’s textbook for advanced students

(my English edition).3

I was delighted that my Ladino courses attracted so many students, and

students of such diverse religious, ethnic, national, racial, and

linguistic backgrounds, including a few of Sephardic heritage.

I started teaching my basic

Ladino Language and Culture course in January 2000. In response to

student demand I offered it every semester, except for my sabbaticals,

through Spring 2017, my last teaching semester at Tufts. Ladino was part

of the Program in Judaic Studies and cross-listed with Spanish. I also

offered Ladino continuation courses on request. They ranged from

independent studies with one student to small classes of five to ten

students. Some chose to continue for several semesters (until

graduation!) and even completed Matilda’s textbook for advanced students

(my English edition).3

I was delighted that my Ladino courses attracted so many students, and

students of such diverse religious, ethnic, national, racial, and

linguistic backgrounds, including a few of Sephardic heritage.

My goal was to teach la lingua biva, the living language. Our main textbook was Matilda’s beginners’ text, a combination grammar, workbook, and cultural resource that includes a historical introduction, traditional and contemporary songs, folk tales, proverbs, essays, and conversations, all reflecting the richness of the language and culture and the genius and versatility of the author. I also made Matilda’s book of verb tables4 available for those interested. Of course, I introduced songs, stories, traditions, and Sephardic style foods associated with Jewish holidays that occurred during the semester, in addition to other stories and songs (including some of mine), films, and relevant news and events. I encouraged my students to share their own discoveries and experiences, and they responded enthusiastically. We enjoyed attending events together like local performances of Ladino music and were even joined on occasion by their Ladino-speaking relatives.

I began every Ladino class with our typical greeting: Ke haber? Literally, What news? Ke – what, from Spanish, and haber – news, from Turkish, a wonderful blend of two major components of the language. The answer I hoped for was Todo bueno. Everything’s good. But I also taught No demandes! Don’t ask! The atmosphere of Ladino class was casual but lively. As is customary in the living language, we all addressed one another using first names and the familiar form, tu. But we worked hard. I’ve always been determined to make every student the best he, she, they can be. We also laughed a lot, reflecting the predominantly optimistic view of the culture. We spoke in Ladino as a class or in smaller groups, using English when necessary, for clarity or complex discussions. We sang in almost every class. And at the end of the class hour, we said Al vermos! See you!

Course assignments and requirements were intended to promote as well as to demonstrate learning. Regular homework assignments, written and oral, were designed to foster creative, personally meaningful use of the language. There were two exams: the first at mid-semester and the last at the end, with possible but rare examenikos, little exams, announced or not. Exams were usually all in Ladino, with ample opportunity to display not only mastery of the language, but knowledge and understanding of the culture as well. Students were asked to formulate their impressions of the language and offer their ideas to insure its continued survival and development. There were always options for extra credit, which could improve the overall exam grade. After mid-semester, each student had to write a poem in Ladino, whether or not they had ever written one in English: this exercise helped make a language their own! Indeed, the students’ poems were typically personal and meaningful, some of their best work.

The course project, due towards the end of the semester, could be on any subject and in any medium, with my approval, as long as it incorporated elements of both language and culture. Students could work together, but they had to specify individual contributions. Students went all out for the project, producing masterpieces such as original Ladino songs, plays, stories, books, poetry collections, games, videos, paintings, drawings, food … and, of course, essays on historical or cultural topics, including personal and family histories. Projects like food or art had to be accompanied by a short write-up. Students were encouraged to present and share their projects, so that when they were due the class became a veritable celebration, a combination party, concert, sing-along, lecture, discussion, bazaar, fair, and dinner.

Towards the end of the semester students submitted their Vokabulario personal, Personal Vocabulary, composed of all the words and expressions in Ladino from whatever source - textbook, class, independent discovery – that they wanted to remember. They were told to start collecting on the very first day of class and reminded periodically. Some students included not only words, but also proverbs and songs and even verb conjugations. The Vokabulario Personal was meant primarily as a personal resource, especially because there was no Ladino-English, English-Ladino dictionary suitable for beginners. Since students were encouraged to choose the best format for themselves, submissions ranged from handwritten lists to typed and printed volumes, from illustrated colored index cards to computer files.

I learned a lot from my students. For example, I was excited to learn of the Persian origin of many words I had known only as Turkish from a student who knew his ancestral language - and became an accomplished poet in Ladino. I shared my new knowledge with subsequent classes, always naming my sources. There were some students closer in age to me who had grown up with Ladino. They came to learn more, and enriched the class. All were welcome. After the first class of twelve, Ladino typically attracted twenty to thirty students, until the Department limited our class size to fifteen. It was a pleasure for me to see us become, as diverse as we were, a real family, la famiya del Ladino! Many students came to love Ladino so much that they began singing our songs in the shower, teaching proverbs to their parents and siblings - really becoming bearers and transmitters of Ladino language and culture. One recent student, who has already become a recognized expert on aspects of the culture, listed Ladino together with Spanish and Hebrew on graduate school applications, recognizing and proclaiming its legitimacy and value. I have known so many extraordinary Ladino students that I cannot, in all fairness, select just a few to name and discuss. Getting to know these special people, many of whom have become friends, has been one of the greatest pleasures of teaching the language.

The success of my Ladino courses reflects the magical attraction of this language. Students are excited to recognize the many other languages and complex historical forces that have enriched Ladino, while they embrace wholeheartedly la lingua biva itself, the unique living language and culture with a flavor all its own. Many are especially attracted by the positive outlook and relevant wisdom of the proverbs, which they find personally meaningful and helpful. They also like the refreshing frankness of the language, which uses perfectly acceptable simple verbs to describe bodily functions. Quite a few students said that they always felt better after Ladino class! The fact that so many were eager to learn Ladino also shows that students do not, as is often claimed, necessarily favor the practical. What could be less practical than learning a language considered “severely endangered,” so you have to look for people to speak it with?!5

There were many special

celebrations of Ladino language and culture at Tufts. We were lucky to

have Matilda Koén-Sarano star in a Sephardic Festival one year, and,

later, in a Festival of Djoha. My students surprised Matilda with a

rousing rendition of her song Diálogo de amor - their idea! With

the help of Tufts colleagues, the Festival of Djoha explored this folk

personage also in his Turkish, Egyptian, Greek, and Italian incarnations

and revealed his origin in India. Since 2013, when International Ladino

Day was first instituted in Jerusalem and celebrated worldwide, until

2016, my students starred in our annual celebration, the only one in the

Boston area. We were joined by Ladino speakers and other interested

guests from and beyond the area. We spoke, sang, shared poems, reported,

ate, and enjoyed celebrating together, an ever growing famiya del

Ladino.

There were many special

celebrations of Ladino language and culture at Tufts. We were lucky to

have Matilda Koén-Sarano star in a Sephardic Festival one year, and,

later, in a Festival of Djoha. My students surprised Matilda with a

rousing rendition of her song Diálogo de amor - their idea! With

the help of Tufts colleagues, the Festival of Djoha explored this folk

personage also in his Turkish, Egyptian, Greek, and Italian incarnations

and revealed his origin in India. Since 2013, when International Ladino

Day was first instituted in Jerusalem and celebrated worldwide, until

2016, my students starred in our annual celebration, the only one in the

Boston area. We were joined by Ladino speakers and other interested

guests from and beyond the area. We spoke, sang, shared poems, reported,

ate, and enjoyed celebrating together, an ever growing famiya del

Ladino.

Immediately upon leaving Tufts, I was blessed with a student who wanted to learn Ladino, even without a class, and who even found us a wonderful place to meet. The place we first met for our Ladino sessions is the Diesel Café in Somerville. Most recently, we’ve been meeting in Hyannis. That student is Emma Youcha, who also presented at the International Ladino Day celebration in New York on January 12, 2020, as part of the “Generation Y and Z Ladino” panel. The pleasures of teaching Ladino continue!

I want to close this essay, as I did my presentation in New York, with a quintessential wish in Ladino. To each one of you: El Dio ke te dé salú i vida!, May God give you health and life! As in my song based on this wish, the wish becomes expanded, extended to all of you together - El Dio ke vos dé salú i vida!, then to all of us - El Dio ke mos dé salú i vida!

In New York, I proposed that mos should also include “our” language, Ladino - it is, after all, alive, la lingua biva! In our context, mos acquires yet another meaning. Each one of you reading this essay and I, “all of us,” are being brought together as part of the community of Judith Roumani’s wonderful Sephardic Horizons, now celebrating its 10th anniversary! May God give us all - people, language and culture, and fostering communities like Sephardic Horizons - health and life! El Dio ke mos dé salú i vida!

* Gloria J. Ascher, Associate Professor of German, Scandinavian and Judaic Studies Emerita, Tufts University, writes poems and songs in Ladino and teaches the language independently.

1 Many scholars favor “Judeo-Spanish,” which is obviously a construct and refers not only to what is commonly called Ladino, but to Haketia as well. I chose to use “Ladino” in the title of my course because it is the most common designation, though I do realize that it originally referred only to the written language into which sacred texts were translated. I also know that “Ladino” is the name of another language, spoken in Switzerland.

2 Matilda Koén-Sarano, Kurso de Djudeo-Espanyol (Ladino) para Prinsipiantes/Course in Judeo-Spanish for Beginners (Beer-Sheva: The J.R. Elyachar Center, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, 1999/2002). Before the publication in book form I prepared handouts for students, lesson by lesson.

3 Matilda Koén-Sarano, Kurso de Djudeo-Espanyol para Adelantados/Course in Judeo-Spanish for Advanced Students (Beer Sheva: The J.R. Elyachar Center, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, 1999/2002).

4 Matilda Koén-Sarano, Tabelas de Verbos en Djudeo-Espanyol (Ladino) (Jerusalem, 1999, published by the author).

5 A wonderful example of the attraction Ladino has for younger people is the experience and activity of Kenan Cruz Çilli, a 21-year-old Turkish student. Kenan first heard Ladino on the internet, then learned it through songs and videos on YouTube and newspapers. For Kenan, son of a Portuguese Catholic mother and a Turkish Muslim father, discovering Ladino and its culture and historical implications was “like a bridge between the two parts of my family,” “my two countries,” Portugal and Turkey. Kenan now contributes regularly, in Ladino, to the same newspapers that helped him learn the language. The above quotations are translated from his Ladino article “Komo Empesi a Ambezarme el Djudeo-Espanyol” (“How I Began to Learn Judeo-Spanish”), Şalom, 18 Aralık 2019, p. 16.

All photos courtesy of the Zakaria Siraj.