In Her Own Words

By

Micaela (Michele) Amateau Amato

I grew up in New York in the most beautiful home filled with sounds of opera and flamenco, intoxicating aromas, tapestries, and Turkish carpets with my parents, sister, my beloved Nana, and Papoo. Nearby lived the closely knit, extended families of my father’s nine siblings. We speak Ladino, as you all know, a medieval Spanish with Hebrew, Arabic, Greek, Turkish, and Italian with the addition of French from Alliance education. The cultural, philosophical, and linguistic experiences of Sephardi and Mizrahi people have offered me an unmistakably expansive perspective and identification with many peoples from across the globe. We have flourished where Jewish Hispanic, Jewish Arabic, and Maghreb communities have converged. Through my hybrid ancestry, I have celebrated this confluence and developed cross-disciplinary visual and written bodies of work.

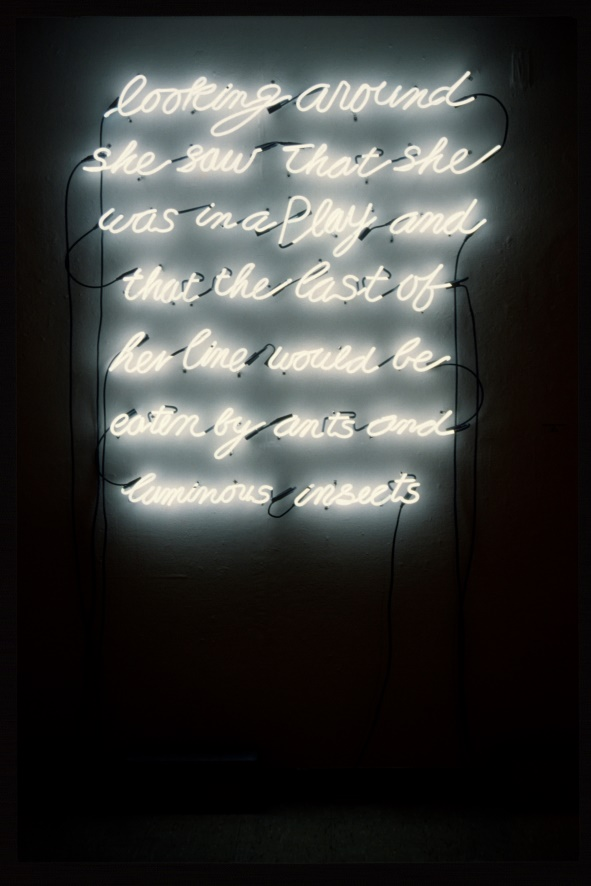

Over the decades, I have made life-size cast glass or ceramic portraits and figurative sculptures with hybrid racial and ethnic physiognomies, combined with ancestral self-portraiture that are simultaneously male and female. Congruently, my paintings incorporate sculpture and photography, while large scale composite color portrait photographs overlap with Egyptian faiyum portraits and other ancient images. Since the 1970s, I have painted the sea that is both earth and wind, like Byzantine water and striations of earth. Composite works are intended to protest a singular perspective, a tyranny of certainty or “purity,” by celebrating multiple voices, and cross-cultural sensibilities, substantial strategies for social justice. In addition, I have made neon-lighted Ladino texts that are private lamentations or cries for justice: “avlar kero i no puedo, mi korazon sospira,” and “montanyas yoran por aire.”

Neon, Micaela Amateau Amato

I have collaborated with my father Aron, using his 1920s photographs from Africa and Turkey, with my daughter Cara Judea’s large scale color photographs and writings, and with my grandson Zazu making sculptures together in my studio. These collaborations evoke private stories and public histories of people in a state of exile and transition, evoking melancholia and longing: duende/saudade. They are grounded in an awareness of the web of the ancient past interconnected within the present and rooted in the natural world. In our escalating state of ecological crisis and war, symbiosis and convivencia offer me substantial strategies, models for radical social change.

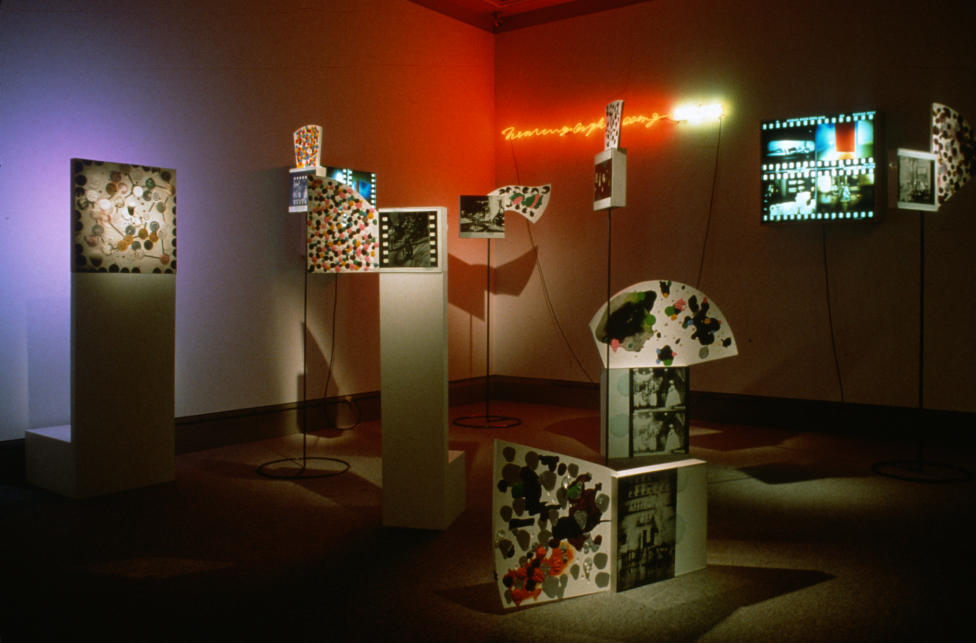

Hearing Light - Seeing Sound,

Micaela Amateau Amato

During the late twentieth century, I became increasingly aware of the existence of hidden or Crypto-Jews and Crypto-Muslims/Moriscos, aljamas, anusim, “forced ones,” who have hidden their Semitic ancestry for centuries, often under the mask of Catholicism, practicing Judaic and Islamic traditions in secrecy. Across the Americas, the legacy of inquisitional anti-Semitism has given way to the fact that thousands of Latinos, Chicanos, Caribbean, and Hispanics have Jewish or Muslim ancestry. And Ashkenazi communities have had to recognize the implications of their own prejudices against Hispanics, Arabs (and Ethiopian Falashas) who they now recognize as also being Jewish. “I am you and you are me, all together.” “Je suis juif, je suis musulman, je suis toi.” My exhibition, “Son espanyoles komo mosotros?” at Yeshiva University Museum, Sephardic House, and The Center for Jewish History in 2001, celebrated the defiance of los chuetas, anusim, conversos, by evoking a private space for ancestral healing, for lamentations, and for our ecstatic and euphoric spirit. Many high school students from across New York City who visited the exhibition enthusiastically identified with my celebration of hybrid racial and ethnic identity.

By engaging my own Sephardic history, I have attempted to focus on the deeply empathic humanism of the teachings of Maimonides and Spinoza, too often ignored or disparaged in Ashkenazi Euro-centered Jewish education. Our potential commonalities could bind us to one another to “repair what has been broken.” The cultural experiences of Sephardi and Mizrahi people offer a perspective that bridges the tragic cultural divide between immigrants of “color” and “white people,” an “us” vs. “them” tribal mentality that too often ends in violence and sustains the “divide and conquer” strategies of those in power.

Because of this family ethos of inter-relationality, I developed a strong sense of self early on from my mother and father. In 1951, at the age of six I began drawing lessons with the artist Guiseppe Trotta. Even as his youngest student, I recognized that I deserved respect from Professor Trotta, and requested that he call me by my name: “My name is Michele…please do not call me ‘girlie!’” Seven years later in 1958, I was the first girl in Queens and Long Island, New York, to study for and perform the Bat Mitzvah ceremony. And three years later in 1961, as a sophomore, I qualified for the New York State High School Debate Finals in Albany, further defining my critical feminist and Sephardic consciousness. As a sophomore art student at Boston University, I rigorously protested discriminatory rules against female students including archaic dress codes. Although I was suspended for a semester for disciplinary infractions, these arbitrary rules against female students were finally overturned and we were allowed greater freedoms, including the right to wear slacks/jeans and not exclusively skirts (more appropriate when riding bicycles!)

In 1968, I graduated with my BFA, and married Albert Alhadeff at Shearith Israel Synagogue.* Three Rabbis presided, including Rabbi David de Sola Pool, who came out of retirement for our wedding. Eventually we moved to Boulder, Colorado, and in 1971, I gave birth to our daughter, Cara Judea Alhadeff. Art critic Lucy R. Lippard asked me to serve as Western States Representative for East West Bag, WAR, and NOW. In 1969, I initiated the University of Colorado’s Graduate Women’s Coalition and was instrumental in the hiring of the first female faculty hired in the art department. In 1974, I was co–editor of the College Art Association’s Women’s Caucus for Art Newsletter, where I covered the new Federal Affirmative Action Program.

From 1973-1977, I was art and performance critic for The Boulder Daily Camera, Denver’s Straight Creek Journal, and wrote for HERESIES, Ocular Magazine, and ART PRESS Paris, where I published extensive interviews with art world luminaries Paula Cooper, Lucy Lippard, and Nancy Hoffman, and museum directors Henry Hopkins and Marcia Tucker. Throughout the 70s and the 80s, I curated dozens of exhibitions: at the Patrick Gallery, Austin, Texas (“Mysterious Messages and Sculpture for the People” in support of % for Art Legislation); and “Preparatory Notes/Thinking Drawings” at New York University, chosen by the Village Voice as PICK OF THE WEEK.

Painting, Micaela Amateau Amato

In 1974, I began exhibiting my paintings annually at the blue chip Kornblee Gallery in New York City, then in Los Angeles and Chicago, with major reviews of my work in Artforum International, Art in America, Art News, The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, and more. My work is collected by Albert and Vera List, Carol and Arthur Goldberg, the Rockefeller Collections, and many other private and public collections, including Marieluise Hessel Museum at Bard College, The Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University, the Museum of Art and Design, NYC, and the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago.

Installation, Micaela Amateau Amato

In 1977, I became the first female ever to be hired as Head of the Graduate Painting Program at Wichita State University, in Wichita, Kansas. I joined the faculty at Penn State University in 1987 to teach painting and the History of Women Artists in the Twentieth (21st) Century. After four years, not the usual six, I received tenure in 1991, and in 1993, I was the first woman promoted to professor in The School of Visual Arts. In 1994, I received The Distinguished Achievement Award from Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies; I was awarded Professor Emerita in the College of Art & Architecture in 2006. While at Penn State, I curated “Gender & Representation,” “Couples’ Discourse,” and “Uncanny Congruencies” at the Palmer Museum of Art where I published two exhibition catalogues with Penn State University Press.

In the early 1990s, I was diagnosed with an environmentally-caused leukemia from benzene. The head of hemotology at Sloan Kettering Hospital gave me six months to two years to live. However, since my father had had a botanica in Spanish Harlem for over forty-five years where he sold medicinal herbs and oils, I understood I had options to determine my own path to recovery. I refused chemotherapy and began a regimen of herbal medicines (Chinese/Ayurvedic, etc.) to rebuild my immune system. I worked hard to bring my platelet count down from almost two million to 200,000s over a period of twenty years. Eventually, the Penn State Art Department banned the use of turpentine, sprays, and other lethal art materials. I continue to work for local legislation and community support banning toxic building materials, petroleum plastic bags, bottles, and packaging and advocate for the elimination of pesticides, formaldehyde, and other environmental poisons from our water supply, land, and air.

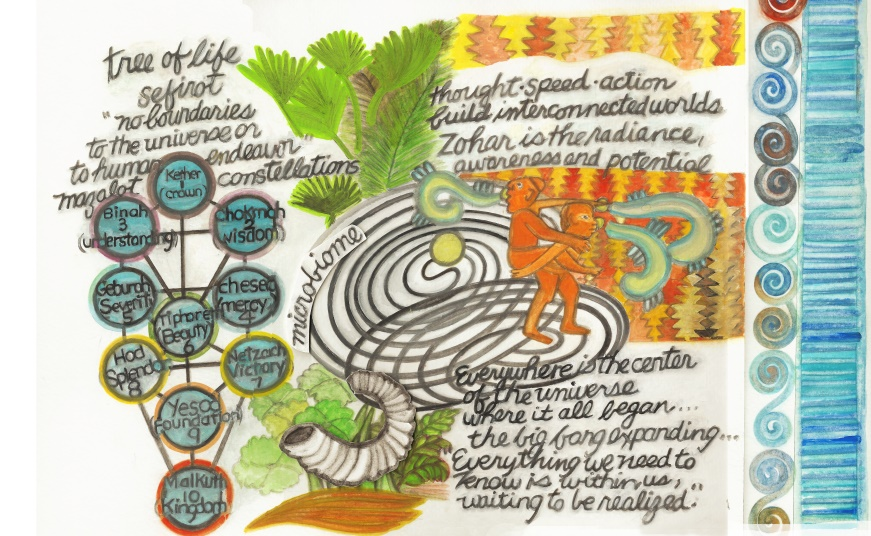

From Zazu Dreams, Between the Scarab and the Dung Beetle,

A Cautionary Fable for the Anthropocene Era, Micaela Amateau Amato

In 2017, I illustrated Zazu Dreams, Between the Scarab and the Dung Beetle, A Cautionary Fable for the Anthropocene Era written by Cara Judea Alhadeff, Ph.D., my daughter. The National Liberty Museum in Philadelphia chose me as Honoree for the 2019 International Year of the Woman with my solo exhibition, “Welcome the Stranger.”

Installation, National Liberty Museum, 2019

* Albert and I were divorced and I later married sculptor Don Schule.