Guadalajara: A Fifteenth Century Hebrew Press of Distinction

By Marvin J. Heller*

One of the earliest Hebrew presses of distinction is now little-recalled except by antiquarians and in bibliographic circles. That press, briefly active in the fifteenth century, was in the Spanish city of Guadalajara. A respectable if not significant number of varied titles were published there from 1476 through 1482.

Located on the Henares River northeast of Madrid and 113 km. (70 miles) from Toledo in Castile, Guadalajara is the capital of Guadalajara provincia (province) in Castile-La Mancha. It was, much earlier, the ancient Arrica, controlled for a time by the Romans. Its current name, Guadalajara, is of Arabic derivation (Wādī al-Ḥijārah, River of Stones).1 Jewish settlement in Guadalajara dates to at least the eighth century when a community is known to have been present. The Berber general Ṭāriq ibn-Ziyād (d. ca. 720), who led the Muslim conquest of Spain, conquered Guadalajara in 711 and found Jews already resident there. He entrusted them with the city’s defense, making them guards of the conquered city.2

Guadalajara was reconquered by the Christians in 1085. The Jews appear to have prospered there. Jewish notables had communal prerogatives and received income from the slaughter houses. They were criticized in 1281 for this activity by the moralist, mystic physician R. Isaac ben Solomon Aba Sahula of Guadalajara (13th century) in his Meshal ha-Kadmoni for ruling “high-handedly in the manner of Jeroboam” so that they have no portion in the world to come. Notwithstanding its population, which towards the end of the thirteenth century consisted of only about twenty to thirty families, the community remained distinct. It appears to have declined at this time, for Yitzhak Baer informs that two houses were transferred from Jewish ownership to Franciscan convents.3

Along with other Jewish communities in Spain, the Jews in Guadalajara suffered during the 1391 massacres; a mass conversion of 122 Jews occurred in 1414. Anousim in Guadalajara were so numerous that King Juan II ordered the city to treat baptized Jews like born Christians and to give them official positions.4 Jewish residence, until 1412, was in Castil de judíos, outside of the walls of the city. Afterwards, it was near San Adrés, the city’s commercial center, near San Gil, Santa María de la Fuente, and San Miguel. The judería was also inhabited by non-Jews until 1480 when attempts were made to isolate the Jews from their Christian neighbors.

Despite all of this, the community appears to have been financially sound, for a tax of 11,000 maravedis was levied as late as 1439. Guadalajaran Jews were still tax farmers in the fifteenth century; during the war against Granada the tax paid by the Jews of Guadalajara, 104,220 maravedis in 1488 and 90,620 maravedis in 1491, was one of the highest of any Jewish community.5 Parenthetically, an example of Jewish business activity with Christians is a two folio lease in the National Library of Israel dated February 7, 1462. It is signed by Yuce Albelda, a Jew, who leased a salt factory from Pedro de Mendoza, a Christian in Altenza in Guadalajara Province (“Sepan quantos esta carta vieren como yo don Yuce Albelda judio...”)6.

In addition to R. Isaac ben Solomon Aba Sahula (above), other distinguished residents of Guadalajara include R. Solomon ben Abraham ben Yaish (13th century), who wrote on Ibn Ezra's commentary on the Torah; R. Moses Arragel (ca. 1400–1493), who translated the Bible into Castilian; and the renowned Kabbalist R. Moses de León (1250-1301). Another person of repute is Solomon ben Moses ha‑Levi ibn Alkabetz (n.d.), who established a Hebrew press in Guadalajara in 1476.

Book printing was then in its earliest stages. The first books printed in the fifteenth century are called incunabula (Latin, cradle books). To fully appreciate just how early the phenomenon of Hebrew printing in Spain was it should be noted that the first book printed with movable type, the Gutenberg Bible, the 42-line Bible, only appeared in 1455. The first Hebrew books were printed in Rome in about 1469 by Obadiah, Manasseh, and Benjamin of Rome. The first dated Hebrew book, Rashi’s commentary on the Torah printed by Abraham ben Garton in Reggio di Calabria, was completed on Friday 10 Adar, 5235 (February 26, 1475).7 Joshua Bloch writes that Hebrew printing which began in Italy “spread soon to Spain and Portugal, flourished there for a short while before it perished at the hands of the Inquisition.”8

In the Iberian Peninsula, the first printed books were Obres o trobes en lahors de la verge Maria in Valencia and Manipulus Curatorum of Guido de Monte Rocherii in Saragossa in 1475.9 Bloch writes that the first Hebrew press in Spain was likely that of Juan de Lucena (1430–1506), in his home in Montalbán as well as in Toledo where he also maintained a house. His output was probably liturgical works. Among those who assisted him were two of his six daughters. Teresa de Lucena was tried twice for having printed Hebrew books and for secretly Judaizing and for being a nominal Christian. She was sentenced at the second trial to life imprisonment.10

Solomon ben Moses ha‑Levi ibn Alkabetz’s name is better known due to his being the eponymous grandfather of the Kabbalist R. Solomon ben Moses Alkabetz (ca. 1505-76). The latter was the author of several works, among them Manot ha-Levi (Venice, 1585) on Megillat Esther and Lekhah Dodi, the hymn sung by Jewish communities throughout the world to greet the Sabbath. The printer Solomon ben Moses Alkabetz was descended from a distinguished Sephardic family. His father, Moses, is mentioned in several responsa of R. Isaac ben Sheshet (1326-1408).11 Alkabetz published the oldest extant Sephardic Hebrew imprint, Perush Rashi al ha-Torah, dated in the colophon as 16 Elul, 5236 (September 14, 1476).12 He was assisted in the press by Abraham ben Garton, who had returned from Italy; Alkabetz’s sons, Joshua and Moses, who helped him with the press; and Pedro de Monbil, who assisted with the typographical work and designed and cut the letters.13

How many and what titles were printed by the Alkabetz press in Guadalajara? Bibliographic sources differ. They give varied book numbers. Yeshayahu Vinograd records titles from several sources and lists twenty-six works, although he notes that some are questionable. A. K. Offenberg lists only fifteen items in public collections. Moreover, Offenberg cites works printed together as a single entry while Vinograd records them as separate entries. For example, Offenberg (53) lists a Haggadah with Haruzim (rules for calculation for the calendar, 1351/2 [1599]), Megilat Antiokos (sic), Mi-Khamokha, Tefilat ha-Derek, and Benedictions. The first two were recorded by Vinograd as separate entries.14

This listing is compounded by the comments of Lazarus Goldschmidt who suggests that many books misidentified as incunabula, that is books printed before 1500, are actually later imprints. Concerning one example, he writes “Special care must be taken when dealing with Guadalajara prints. As has already been mentioned several times, the later Salonika and Fez prints use the same type.”15 Elsewhere, Goldschmidt writes that “the Fez or Salonika print of the Talmud tractate Kiddushin, which this institution [British Museum] hitherto possessed as such, has advanced to the status of an unknown incunable with the remark ‘printed Guadalajara by Solomon Alkabets (sic), which piece of information is imagination.”16 To avoid the errors ascribed by Goldschmidt to false attributions of Guadalajara imprints we have, in addition to the sources noted above, also relied on the catalogue of the Jewish National Library and Shimon Iakerson’s catalogue of the Hebrew incunabula in the Jewish Theological Seminary.17

Goldschmidt expresses a low opinion of the quality of the Guadalajara presswork as “miserable and hardly legible.”18 His comment is in contrast to Bloch who, writing about the Spanish Hebrew imprints in general, distinguishes between the early and later works, the former obviously including Guadalajara. Bloch writes,

“The Hebrew books they produced, in a measure, reflect the degree of culture, the scope of interest and the material and intellectual activities of the time. The quality of paper, the frequent use of vellum, the shining lustre of the ink, the style and ornamental designs of the letters and borders – all indicate a life of ease, comfort and even security.”19

I

There is no disagreement that the first Guadalajara imprint was Rashi’s commentary on the Torah, Perush Rashi al ha-Torah. It was printed soon after the Reggio di Calabria Rashi (1475).20 I. Sonne suggests that the first of these two editions was marketed in Spain and quickly reprinted in Guadalajara, its primary market. The Guadalajara edition was originally known only from a fragment, until Sonne discovered the only known complete copy in the Biblioteca Capitolare in Verona.21 In addition to Perush Rashi al ha-Torah, the books credited to the Alkabetz press, in the approximately six years that it was active (1476-1482), include R. Jacob ben Asher’s (ca. 1270-1340) Arba’ah Turim, Megillat Antiochus, R. David ben Joseph Kimhi’s (Radak, ca. 1160-ca. 1235) commentary on Nevi’im (Earlier and Later Prophets), and Talmudic tractates, the largest part of the press’ publication.

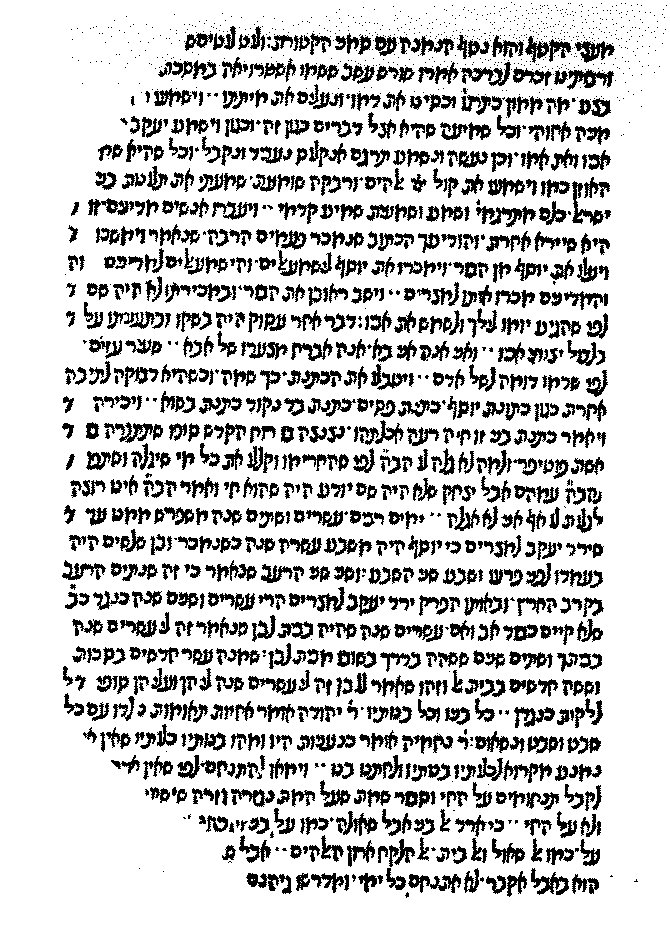

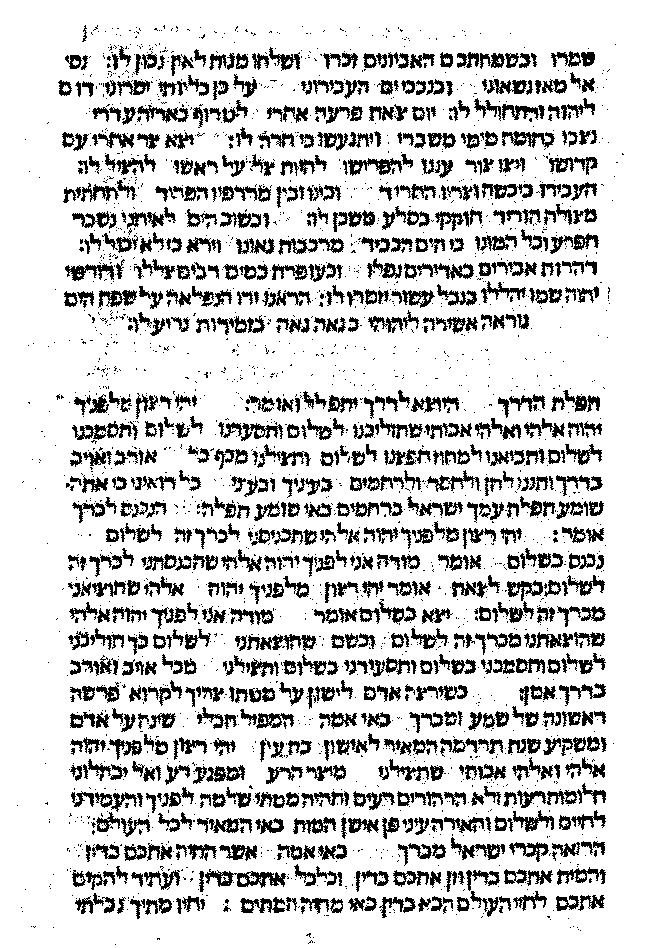

Alkabetz’s edition of Rashi’s Torah commentary is printed in a Sephardic cursive font, the colophon only in square letters. The volume is a folio (20: measuring 26 cm.) various sources give different foliation from [115] to [190] leaves, several blank.22 There is no title-page as incunabula replicating manuscripts often lacked title-pages. The first Hebrew book with a title-page was Sefer ha‑Roke’ah (Fano, 1505)23 by R. Eleazar ben Judah of Worms (ca. 1165 - ca. 1230). Also, in contrast to the later Sephardic imprints Alkabetz’s publications did not have ornamental borders or designs. The text is set in a single column, 31 lines to a page. An innovative aspect of the Alkabetz edition of Rashi is that it is the first printed book to name the editor.24

In several instances the text of the Guadalajara edition of Perush Rashi al ha-Torah varies from our standard Rashi commentary on the Torah. Menahem Mendel Brachfeld, in Yosef Halel, notes that numerous errors in more recent editions of Rashi are due to errors in transmission, frequently compounded by editors, printers, and the unkind modifications of censors25. Alkabetz admittedly corrected the text according to his own reasoning. Sonne suggests that Alkabetz had only one copy to work with, either the Reggio de Calabria edition or a single manuscript. Ch. B. Friedberg, in contrast, writes that Alkabetz worked from several manuscripts.26 A third and different opinion is that of Shimon Iakerson who writes that “it should be noted that bibliographical literature has tended to connect the two editions and to associate Abraham Ben Garton, one way or another, with the work of Solomon Alkabetz, but there is no evidence to warrant this. Without any doubt we are dealing with two different editions by independent artisans.”27

Iakerson’s argument is cogent. However, after returning from Italy, Abraham ben Garton was associated with the Alkabetz press and the editions share a proximity in time. It would seem most likely, therefore, that the former’s Perush Rashi al ha-Torah was available to and influenced the latter in his preparation of that work.

Perush Rashi al ha-Torah, 1476

Aron Freimann and Moses Marx, Thesaurus Typographiae Hebraicae Saeculi IV

In either case, Alkabetz’s editing was not unique. Sonne notes his editing procedures were comparable to those of other early copyists and printers and strongly criticized by Gershom Soncino, the most prominent printer of Hebrew incunabula among early sixteenth century printers.28 Using the Reggio di Calabria and other early editions, Brachfeld records emendations to current texts, resulting in errors in transmission. Two examples from the Guadalajara edition are:

Leviticus 10: 16) The goat of the sin-offering, the goat of the additional service of the month and the three goats of sin-offering sacrificed on that day, the he-goat, the goat of Nahshon, and the goat of [Rosh Hodesh], etc. According to this version it is not clear what Rashi is suggesting by the he-goat. In the first edition (Reggio di Calabria) and the Alkabetz edition, the text is three goats of sin-offering sacrificed on that day, take a he-goat and the goat of Nahshon, etc. and with this Rashi alludes to the verse at the beginning of the parasha that speaks about the obligatory offerings of the day, writing take “a he-goat.”29

Leviticus 26: 21) Sevenfold according to your sins, seven other punishments, etc. Seven שבע is in the feminine, and others ואחרים is male. In the first edition and in the Alkabetz edition the text is seven other punishments, as the number of your sins 30.חטאתיכם

II

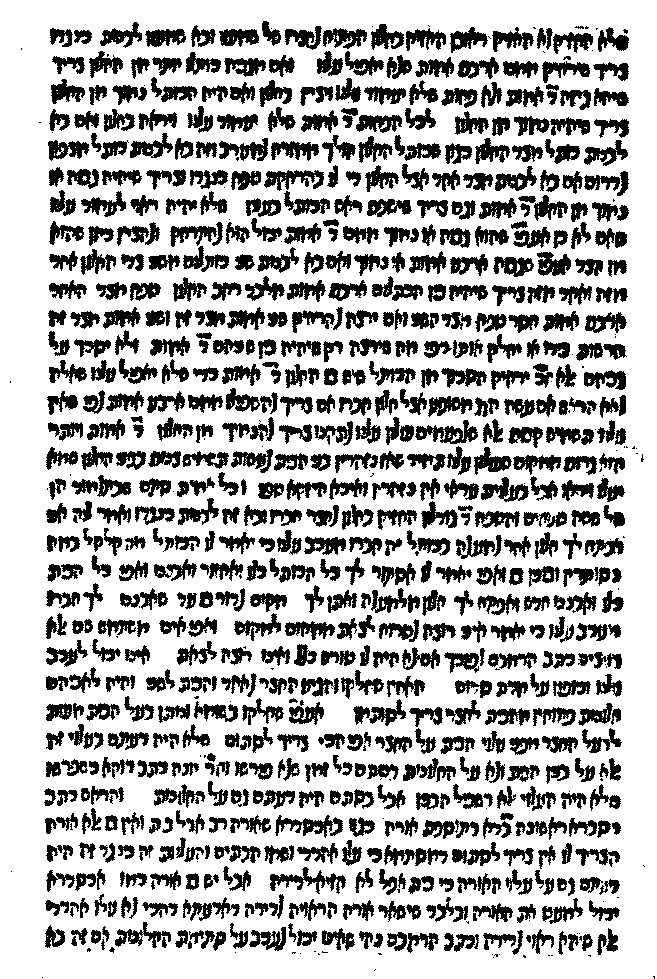

David Kimhi, Nevi'im, 1482

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

Arba'ah Turim, Hoshen Mishpat,1481

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

The second work from the Alkabetz press is the multi-volume Arba’ah Turim, which was printed over several years. R. Jacob ben Asher (Ba`al ha-Turim) is the basis of subsequent halakhic codes to the present. It is concerned with laws currently applicable; those inoperative in the absence of the Temple are omitted. It has been the subject of commentaries that are major halakhic works in their own right, notably R. Joseph Caro’s (1488–1575) Beit Yosef and R. Moses Isserles’ (Rema, ca. 1525/30–1572) Darkhei Moshe. Its organization has been followed in later halakhic works, most notably the Shulhan Arukh. As recorded in bibliographic sources, the first volume, printed by Alkabetz in 1479 is Yoreh De’ah ([128] ff.), followed in 1480 by Even ha-Ezer ([112] ff.), and in 1481 Hoshen Mishpat ([271] ff.,).31 Joseph Y. Kohen suggests, most reasonably, that many early works were selected to be printed due to their functionality. It is likely the Tur Orah Haim was the first volume in that series to be printed.32

The next Alkabetz imprint is the commentary of R. David ben Joseph Kimhi (Radak, ca. 1160-ca. 1235) on the Nevi’im (Prophets) of the Bible. Printed in 1482 in quarto format (Nevi’im Ahronim 40: [315] ff.), it is the first printing of this work, republished to the present day in all rabbinic Bibles. Kimhi regarded the writing of his commentaries as a religious duty, one that he categorized as ma’asim tovim (good deeds). The primary emphasis of Kimhi’s commentary is peshat (literal interpretation). In his interpretation of the text, Kimhi avoids the homiletic discourses popular in his time although he does make use of aggadic interpretations. Philology is an important aspect of this commentary and, strongly influenced by Maimonides, some events and visions are explained philosophically.

III

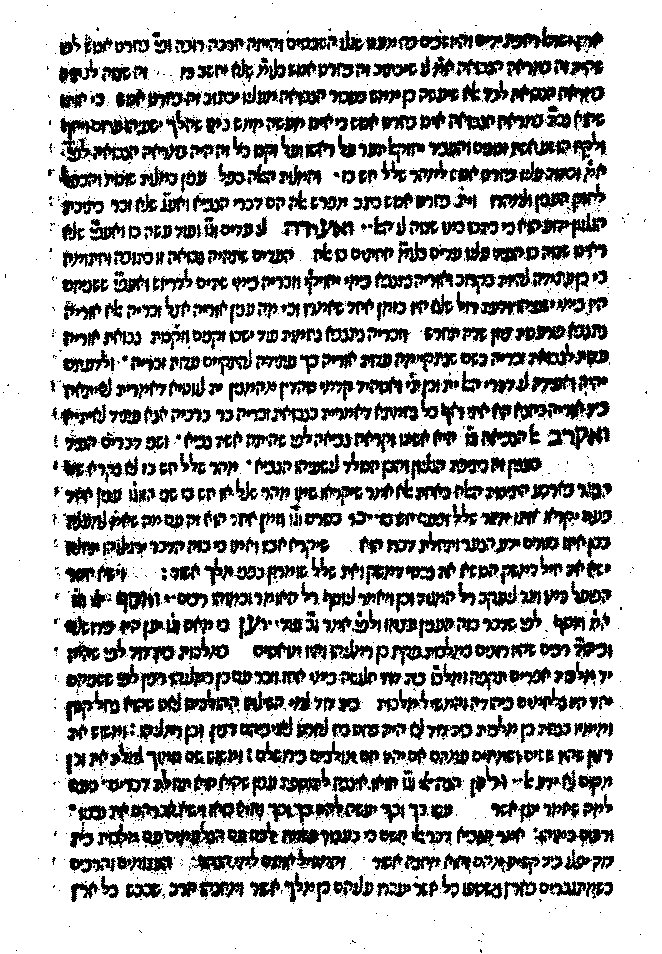

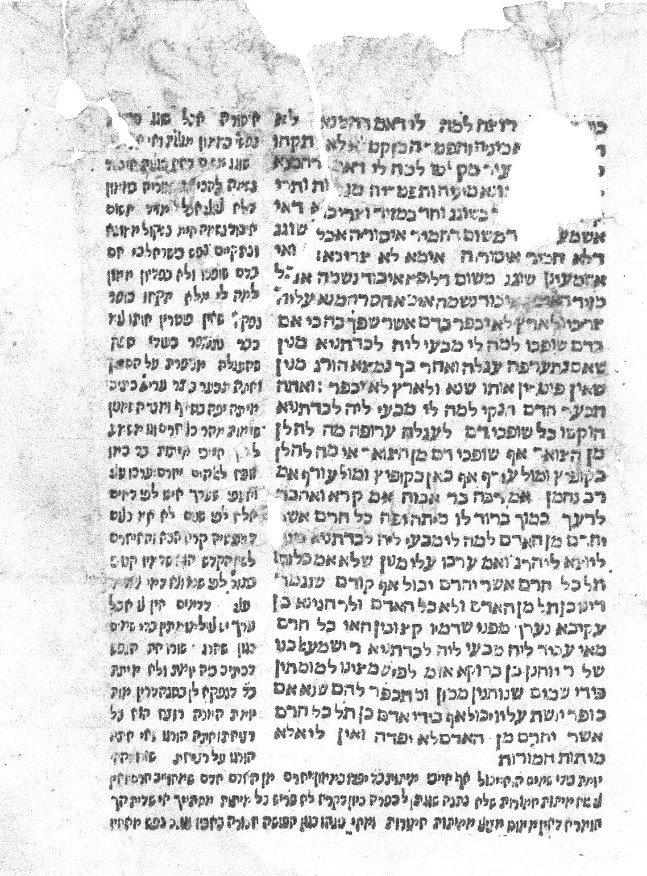

Yet another work printed by Alkabetz is the multi-part work comprised, according to Offenberg, as noted above, of a Haggadah, Megilat Antiochus, Tefilat ha-Derekh, and Mi-Khamokha, folio in format, with the comment “part of a prayerbook?”33 The National Library of Israel records the Haggadah and Megilat Antiochus with the other works separately, as two independent works both dated 1482 and quarto in format. The Haggadah (below left) was printed in two columns in square letters as a quarto (40: 6 ff.), the text beginning “When he comes from the synagogue the cups are rinsed and filled with mixed wine.”34

Megillat Antiochus (40: [7] ff.) incorporates portions of the Books of Maccabees, commemorating the victory of the Jews under the leadership of the Maccabees over the Greeks and their hellenizing supporters. Modeled after the Book of Esther it is believed to have been written in Aramaic; the date of composition is indeterminate. Some authorities date it between the mid-eighth to the mid-ninth centuries. Others, such as Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, see it as a much earlier work. The latter writes that “probably dating from the late Talmudic period (its Aramaic language indicates the period between the second and fifth centuries C.E. in Palestine).” 35 A popular work, it has been translated into Hebrew and a number of other languages. The Alkabetz is the first separate printing. It, too, is printed in two columns in the same square letters as the Haggadah. The text is in Hebrew and Aramaic. The remaining parts of the volume, the Tefilat ha-Derekh, and Benedictions, are in a single column in square letters (below right).

Haggadah, 1492

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

Tefilat ha-Derekh,1492

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

Another item recorded for the Alkabetz press in the National Library of Israel catalogue is a calendar dated 1482. It is likely that as long as the press was active, additional calendars and other small items classified as ephemera were printed. Such items, by their very nature, were meant to be discarded after being used and rarely retained. Given the chaotic nature of Jewish life in Spain at the time, the retention of such objects is to be wondered at and appreciated

IV

The final and largest portion of Alkabetz imprints are Talmudic tractates. The number and publication dates of the tractates are unknown, as noted above. The Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book records twelve tractates while Offenberg lists eight tractates in public collections. The tractates they agree on are Berakhot, Yoma, Bezah, Ta’anit, Mo’ed Katan, Hagigah, Ketubbot, and Kiddushin.36

Alkabetz published the first tractates in about 1480. Haim Z. Dimitrovsky notes the following differences between them. The first treatises are printed with letters principally like those used in the Rashi Torah commentary. The fonts employed in Ketubbot are like those in the Radak’s Nevi’im. Also, the fonts used in Ketubbot are worn. Dimitrovsky infers from this that Ketubbot are among the last of the Guadalajara tractates to be printed.37

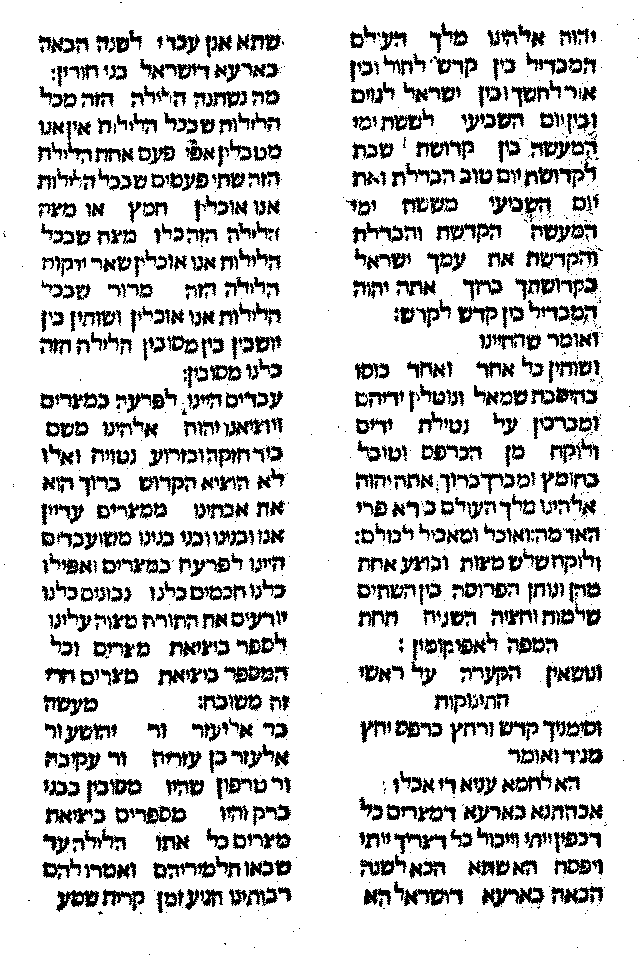

Tractate Ketubbot, 37b, ca. 1480

Courtesy of the syndics of Cambridge University U.L.C. ADD 1053

The Guadalajara tractates are printed with the text in square letters and Rashi is printed in a cursive Sephardic script. Based on the variant manuscripts from which the text was set, Iberian Talmud editions, whether printed in Spain or Portugal, are distinguished by additional features, including textual variations. In most tractates, Rashi appears along the outer margin, with the text toward the center. In contrast, in Berakhot, which may have been the earliest printed Guadalajara tractate, Rashi was always printed along the left side of the page, which resulted in Rashi separating the text. This indicates that the Guadalajara Berakhot was printed before the format followed in the later tractates, that is, the text surrounded by Rashi, had been established.38

Another feature of not only the Guadalajara tractates but also of Iberian treatises is the absence of Tosafot. According to Dimitrovsky, this can be explained by the fact that the Spanish and Portuguese yeshivot learned the Hiddushei ha-Ramban (Nachmanides) in place of Tosafot. There was no need, therefore, to print the latter.39

V

Books in the incunabular period were most often selected to be printed on the basis of their functionality, as previously stated. The books used most often, such as prayer books, were also the most likely to be worn out, often leaving little or no trace of their existence. If, as Goldschmidt suggests, that many books misidentified as incunabula are actually later imprints, it is equally true that the early presses also published many works that are now lost. Bloch notes that Alkabetz was “quite active” during the short period of time his press was productive. He concludes that “it is probably responsible for the issuance of a much larger number of Hebrew books than those with which it is credited today.”40

As stated above, those books most often required by the community, such as liturgical works, are most likely to be the titles worn out and no longer surviving. It is not surprising that with the one exception of the multi-part book described as “part of a prayerbook”41 no such works from the Alkabetz press are extant. This loss due to usage is compounded by Friedberg’s observation that the size of an Alkabetz press run was between three hundred and eighty to four hundred volumes. He adds that if we consider that in 1491 the Inquisition was responsible for burning more than six thousand Hebrew books, not including biblical works, and that in Barcelona alone in April 1498, all the Targum (Aramaic biblical works) were burned, a small number only of imprints from the Alkabetz press could remain.42

In retrospect, the short-lived Alkabetz press is deserving of being remembered with respect and admiration. It produced a respectable number of varied works, almost certainly more than are now known, including prayer books, Humashim, additional calendars, and other ephemera. Moreover, this was done under the most severe conditions. Jewish life in Spain was already deplorable and the expulsion of the Jews was just over the horizon. Yet Solomon ben Moses ha‑Levi ibn Alkabetz established a press, the first Hebrew press in Spain.

Alkabetz’s publications, considering that they are incunabula from an early and innovative period, reflect well upon his efforts. While the first fonts he used, the Sephardic cursive letters, are somewhat unfamiliar today, they are generally clear and attractive, as are all of his books. Indeed, in retrospect Solomon ben Moses ha‑Levi ibn Alkabetz and his press are remembered with respect and admiration.

* I would like to express my appreciation to Eli Genauer for reading this article and for his suggestions.

Marvin J. Heller is an award winning author of books and articles on early Hebrew printing and

bibliography. Among his books are the Printing the Talmud series, The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Hebrew Book(s): An Abridged

Thesaurus, and several collections of articles.

1 “Guadalajara, Spain,” Encyclopædia Britannica, (2011).

2 Richard Gottheil, Meyer Kayserling, “Guadalajara,” Jewish Encyclopedia V. 6 (1910-1906), pp. 101-02.

3 Yitzhak Baer, A History of the Jews in Christian Spain, From the Age of Reconquest to the Fourteenth Century, tr. Louis Schoffman I (Philadelphia,1966), pp. 92-93, 192, 199.

4 Gottheil, Kayserling, “Guadalajara.”

5 Haim Beinart, “Guadalajara,” Encyclopedia Judaica VIII (2007), pp. 115-16.

7 February 26, 1475, is the date according to the Gregorian calendar, adopted in Rome in 1582, in place of the Julian calendar. The Julian equivalent of 10 Adar, 5235 would be February 17, 1475. Concerning dating the books printed in Rome see Moses Marx, “On the date of the Appearance of the First Hebrew book,” in The Alexander Marx Jubilee Volume (New York, 1950), pp. 496-98.

8 Joshua Bloch, “Early Hebrew Printing in Spain and Portugal,” in Hebrew Printing and Bibliography (New York, 1976), p. 15.

9 Catalogue of books mostly from the presses of the first printers showing the progress of printing with movable metal types through the second half of the fifteenth century. Collected by Rush C. Hawkins, catalogued by Alfred W. Pollard and deposited in the Annmary Brown Memorial at Providence, Rhode Island (Oxford, 1910, reprint Mansfield Centre, n. d.), pp. 294, 296; R. A. Peddie, Printing: A Short History of the Art (London, 1927), pp. 144-45.

10 Bloch, pp. 9-16.

11 Peretz Tishby, Kiryat Sepher 61:3 (Jerusalem, 1988), p.521 [Hebrew].

12 Julian September 5, 1476.

13 Ch. B. Friedberg, History of Hebrew Typography in Italy, Spain‑Portugal and the Turkey, from its beginning and formation about the year 1470 (Tel Aviv, 1956), pp. 91-94 [Hebrew]. After the expulsion of the Jews from Spain, Alkebetz’s son Joshua resided in Salonika until his death in 1530. His other son, Moses, subsequently served as a rav in Adrianople, Salonika, and Aram Zoba.

14 A. K. Offenberg and C. Moed-Van Walraven, Hebrew Incunabula in Public Collections: A First International Census (Nieuwkoop. 1990), p. 187; Yeshayahu Vinograd, Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book. Listing of Books Printed in Hebrew Letters Since the Beginning of Printing circa 1469 through 1863 II (Jerusalem, 1993-95), pp. 167-68 [Hebrew].

15 Lazarus Goldschmidt, Hebrew Incunables: A Bibliographical Essay (Oxford, 1948), p. 63.

16 op.cit. p. 72.

17 National Library of Israel, Aleph Catalogue; Shimon Iakerson, Catalogue of Hebrew Incunabula from the Collection of the Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (New York and Jerusalem, 2005).

18 Goldschmidt, pp. 63, 72-73.

19 Bloch, p. 7.

20 "In any case, there is no disagreement that the first Guadalajara imprint was Rashi’s commentary on the Torah"

21 I. Sonne “The Beginnings of Hebrew printing in Spain” Kiryat Sepher 14:3 (Jerusalem, 1937), p. 370 [Hebrew].

22 Iakerson, p. 20; Vinograd, II, p, 167.

23 The first book with a dedicated page, known as a label titles, was the Bul zu dutsch (Papal letter in German, Mainz, 1463), followed by Sermo ad popularum (Cologne, 1470). It soon developed into a more detailed title page, one with a two-color decorative border, the Calendarium of Johannes Regiomontanus, appearing in 1476, (Venice), being a fifty-five year calendar (1475-1530) printed by Johannes Regiomontanus (Philip Gaskell, A New Introduction to Bibliography (New Castle, Del.: Oak Knoll Books, 1995), p. 52; Douglas C. McMurtrie, The Book; the Story of Printing & Bookmaking (New York: Dorset Press, 1989), pp. 561-62).

24 Yakov Shmuel Spiegel, Chapters in the History of the Jewish Book: Scholars and Their Annotations (Ramat-Gan, 1996), p. 201 [Hebrew].

25 Menahem Mendel Brachfeld, Yosef Halel II (Brooklyn, 1987), pp.8-13 [Hebrew].

26 Ch. B. Friedberg, History of Hebrew Typography in Italy, Spain‑Portugal and the Turkey, from its beginning and formation about the year 1470 (Tel Aviv, 1956), p. 92 [Hebrew].

27 Iakerson, I p. XXVI.

28 Sonne p. 372.

29 Brachfeld, p. 36 [Hebrew].

30 Brachfeld, II p. 102.

31 The above foliation is according to the National Library of Israel catalogue Yoreh De’ah. The foliation in Iakerson is, between 1476-80, Yoreh De’ah ([188?] ff.), in 1480 Hoshen Mishpat ([272] and ff.), in ca. 1482 Even ha-Ezer ([112] ff.). Vinograd notes an edition of Orah Hayyim (ca. 1482).

32 Joseph Y. Kohen, “The First Hebrew Imprints and the First Hebrew Printers” in Machanim 106 (Tel Aviv, 1966), p. 104 [Hebrew].

33 Offenberg and Moed-Van Walraven, op cit.

34 Isaac Yudlov, The Haggadah Thesaurus: Bibliography of Passover Haggadot From the Beginning of Printing until 1960 (1997, Jerusalem), pp. 1, no. 2 [Hebrew].

35 Y. Joel, “Megillat Antiochus: The First Printing” Kiryat Sefer (Jerusalem, 1962), 132-36 {Hebrew]; Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, “Scroll of Antiochus” Encyclopedia Judaica 18 (2007), pp. 213-215.

36 The additional tractates recorded in the Thesaurus are Eruvin, Yevamot, Hulin, and Middot. Berakhot, and Yoma, Tractates Bezah, Hagigah, Ketubbot, and Kiddushin are described by Iakerson among the incunabula in the Jewish Theological Seminary. Friedberg lists six tractates only, namely Berakhot, Hagigah, Ketubbot, Kiddushin, Ta’anit, and Yoma in that order.

37 Haim Z. Dimitrovsky, S'ridei Bavli: An Historical and Bibliographical Introduction (New York, 1979), pp. 42-43 [Hebrew].

38 Dimitrovsky, p. 71.

39 Dimitrovsky, p. 17.

40 Bloch, p. 19.

41 Offenberg and Moed-Van Walraven, op.cit.

42 Friedberg, p. 94.

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800

_Guadalajara.png)