Arabic as a Jewish Language Part III1:

The Beginning and the End of Judeo-Arabic

By Sasson Somekh2

I would like now to turn to two groups of Jewish-Arab writing, past and present, which were not written in Hebrew characters and therefore their characterization as Judeo-Arabic has to be explained. The first of these groups appeared at the very beginning of the Jewish Arabic encounter, the second, at its very end. Most or all of the writing produced by Arab Jews in the Middle Ages was done, as we have seen, in the Hebrew script (there are a few exceptions, though for example, within the Karaite communities in the Middle East. Scribes would, for some unfathomable reason, use Arabic script not only in Arabic texts, but sometimes even in the transcription of biblical Hebrew words in Arabic script.)

The Cairo Geniza brought to our attention a whole range of writing models. Owing to the different script a whole literary tradition, separate from the Arabic one, was created by writers of Arabic in Hebrew characters. No similar situation happened in the case of Christian Arabic writing. This is so because the majority of Christian writers throughout the Middle Ages used Arabic script rather than Syriac in their Arabic literature.

Let us now go back to the 6th century AD. In Hijaz, Yemen and other parts of the Arabian Peninsula, Jewish communities and tribes flourished in the period that preceded the coming of Islam in the 7th century. These were for all intents and purposes speakers of Arabic. In their midst there were several poets who composed poetry in the ancient Bedouin style. Arabic sources mention a number of Jewish poets of the period, but for most of them, none of their poetry came down to us. The only Jewish poet whose poetry was memorized by the ruwat [memorizers of poetry who replaced the written text in the absence of a proper script] is al-Samaw'al (Samuel). In the dozen or so known poems of this poet we hear the voice of a proud and self-assured poet, proud of himself, of his tribe or community, and above all of his princely abode in the mountains. For ages these poems were memorized by Arabs in different parts of the Arab world. Al-Samaw'al was also the hero of some Arabian legends that came down to us. He was exceptionally loyal to people around him, and on one occasion he tragically allowed one of his sons to be killed by fighters who demanded from him, the father, to surrender arms entrusted to his custody by another Arabian poet-prince. In the Arabic language up to this day, if you want to praise the loyalty of someone you say "he/she is as loyal as al-Samaw'al." As I showed before, no lineage of Jewish poets who wrote in Arabic in the tradition set by al-Samaw'al came into being in the heyday of medieval Arab culture. This is so because Jewish poets preferred to compose their poetry in biblical Hebrew. It was their intention to counter the Arabs’ pride in the richness of the Arabic language, the language of the Koran. They therefore aimed at presenting the Hebrew language as equally exalted. The resort to Hebrew by Judeo-Arab poets, much as it invigorated the Hebrew language, was detrimental to the continuity of the history of Arabic poetry by Jewish poets, although the memory of al-Samaw'al, the Jewish poet-prince of Hijaz, was fully inscribed in the annals of Arabic literature.

So much for the pre-Islamic Judeo-Arab poems. The second group of texts is the very final group in the history of Arab-Jewish communities. I tried to describe the circumstances under which this group of Jewish writers who had some impact on modern Arabic literature, especially in Iraq, came forth. It happened toward the end of the Ottoman rule, which lasted for 400 years, when many young Jews received, as of the second half of the 19th century, a modern schooling and switched to Arabic-Arabic, i. e., writing in Arabic script and conforming to the rules of proper classical Arabic, the fusha. There is indeed some similarity between al-Samaw’al and the other pre-Islamic Jewish poets of Arabia on the one hand and the 19th/20th century Jewish writers if only in that both groups addressed a general public rather than a communal audience. In fact neither group specifically dealt with Jewish topics as such, as is the case with medieval Judeo-Arabic literature. In spite of this similarity, a number of major differences exist between the two groups:

Whereas the pre-Islamic poets were exclusively poets, the modern writers have embraced a variety of writing genres, unknown to their predecessors: prose fiction, drama, literary criticism and journalistic essays.

.

The printing press and the appearance of periodicals were the vehicles by which a modern writer could reach his audience, and therefore prose became as important as poetry.

Thematically, these writers showed an infinitely greater interest in social, psychological and historical matters than was the case of their predecessors.

Until the year 1948 people were under the impression that the coming generation of Jews in Iraq and other Arab countries were to become more active in Arabic writing, in the way Jewish writers were active in central Europe (and are in America today). Jewish writers and intellectuals could be envisioned playing a greater role in Arabic literature owing, among other things, to their better knowledge of foreign languages and world literature. The Jewish community as a whole would see itself as an integral part of the modern Arab culture.

When the 1948 Arab-Israeli war erupted, many young Baghdadi Jews were indeed exhibiting a growing interest in cultural matters. They wrote and published poetry and fiction, they engaged in the promotion of theatrical groups and of translating world literature into Arabic. Senior journalists in major newspapers came, in the 1930s and 1940s, from within the Jewish community (although they would not publish their names as editors, working as it were behind the scenes). Needless to say that many of the best translators from English and French were graduates of the Alliance and Shammash schools. The full integration of the Jews into the Arab cultural fabric was a matter of time.

All these hopes and ambitions came to a halt toward the end of the 1940s. The great bulk of the Jewish community of Iraq and other Arab counties emigrated to Israel or to Europe and the American continent. Many of these new immigrants who settled, for instance, in Israel, deserted the Arabic they acquired in their original countries, investing their efforts in mastering the Hebrew language. Some writers who began to write in Arabic in the old country switched in due course to Hebrew and are now leaders in Israel literature (e.g., Sami Michael, Shimon Ballas). Critics point to the fact that some Arabic traits can be detected in the Hebrew style of these Israeli writers. This fact is not comparable with the impact of Arabic on the poetry of the Spanish Jewish writers, because the medieval writers knowingly incorporated Arabic literary elements in their writing, even when they wrote Hebrew poetry. In the case of writers like Michael and Ballas, the affinity to Arabic is in most cases unintentional.

Anwar Sha’ul was not only one of the first celebrated modern Iraqi Jewish writers, but he was in fact the one who stayed in the Arab world until the very end. His autobiography gives an indication as to his ‘Jewish Arabness’, his Arab-Jewish identity.

Anwar Sha'ul belongs to the first generation of modern Iraqi Jewish writers. He was born about 1904 in the city of Hilla, in southern Iraq. Early in his life he settled in Baghdad. He became a teacher and lawyer, and pursued a literary career that spanned a full half-century. He stayed in Iraq after the exodus of its Jewish communities in 1950-51, but he too was finally obliged to leave the country. The last 14 years of his life were spent in Israel, where he died in 1984 at the age of 80. In Israel he published a retrospective volume of poetry as well as a sizeable autobiography in Arabic.

In Iraq Anwar Sha'ul engaged in a variety of literary activities. His books include poetry, prose fiction, drama and translations. In 1929 he launched his own weekly cultural journal al-Hasid, which he was able to sustain for 10 years. Al-Hasid hosted many leading Iraqi writers and promoted young authors, Jewish and non-Jewish alike. Sha'ul was highly esteemed by his Muslim and Christian fellow writers and, in 1932, was elected a member of the committee that was designated to host the Indian poet, Rabindranat Tagore, who visited Baghdad that year. Owing to his presence in Iraq after the emigration of most of its Jews, he was lucky enough to be occasionally mentioned in Iraqi literary histories.

He wrote and edited his autobiography, My Life in Mesopotamia, after he had immigrated to Israel, and it was published in Jerusalem in 1980. It records memorable events in his life and literary struggle. Two motifs are paramount in the work as a whole: that of the author's self-image and that of the rise and fall of the ambition of Iraqi Jews to join their voice to the fledgling modern Arabic literature of their country.

A literary autobiography is never a spontaneous recollection. It’s a well-established literary genre, involving selection, organization, and focus. Certain episodes, especially those related in the opening chapters, often assume a symbolic value in autobiographies, often reflecting the author's self-image and life philosophy.

The first five chapters of Sha'ul's autobiography are highly indicative of his sense of identity. Chapter 1 tells us that he was born in the city of Hilla, which he identifies as the site of ancient Babylon on the Euphrates. It is to that site that the exiles of ancient Israel were said to have been deported, and it was there that they chanted "By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, and wept, when we remembered Zion." Thus the author's connection with his biblical roots is forcefully evoked.

Chapter 2 intimates that the author is a scion of Shaykh Sasson, the patriarch of the famous Sassoon family. Here the word ‘Shaykh’ is significant because it denotes that special type of Jewry that is rooted in the world of Islam.

In Chapter 3 the author discloses that his mother, who died shortly after his birth, was in fact the daughter of an Austrian tailor, Hermann Rosenfeld, who had settled in Iraq in the 19th century and married into the family of Shaykh Sasson.

Further on, in Chapter 5, we learn that the author's wet nurse was a Muslim woman, Umm-Husayn. For 15 months she breast-fed the baby boy, together with her own son, 'Abd al-Hadi. The two brothers by nursing met in Baghdad many years later, and there an emotional reunion ensued.

The author's identity as projected in these chapters is, therefore, that of a Jew with biblical roots, part of the modern Jewish people, but retaining deep roots in the Arab-Islamic ethos as well, an Arab-Jew who is proud of being both Jewish and Iraqi.

It is significant then, that the book does not betray a spiteful or bitter tone, although it was written after its author had to desert Iraq for good. To be sure, the bulk of the autobiography records fond memories rather than a sense of disappointment. The non-Jewish personages whom Sha'ul recalls are mostly portrayed as positive characters. In fact the only unpleasant ones in the book are those Iraqis who were in one way or another pro-Nazi. The German ambassador in Baghdad during the 1930's, von Grobba, is singled out as a major factor in the deterioration of Jewish-Muslim relations, and the anti-Jewish pogrom in 1941 is seen here, as in many other Jewish sources, as the beginning of the end of a community that had lived in Mesopotamia for 2500 years.

Admittedly the rise of modern Zionism and the establishment of the state of Israel proved to be detrimental to the dream of integration and harmony that Anwar Sha'ul and other members of his generation nurtured. But anti-Jewish prejudice, as is evident in this autobiography, antedates the involvement of Iraq in the anti-Zionist struggle. Fascist and Hitlerian ideas were becoming fashionable in some Iraqi circles as early as the mid-1920s. At times modern Iraqi intellectuals would reflect, in their words and conduct, some deep-rooted anti-Jewish sentiments. Anwar Sha'ul records an incident that occurred in Baghdad in 1928. A Muslim writer, Tawfiq al-Fukayki, buttonholed him one day to express his admiration for a poem that the young Anwar had recited at a reception held in honor of a visiting Tunisian leader. Al-Fukayki however added wistfully "It is a pity, though, that you are Jewish.” By saying so he was probably trying to tell the young Anwar Sha’ul that he was aware that being a Jew made it difficult for some of his Muslim countrymen to accept him as an Arabic countryman/writer. But Sha'ul retorted, "Why 'pity'? I am quite happy to be Jewish.”

Notes:

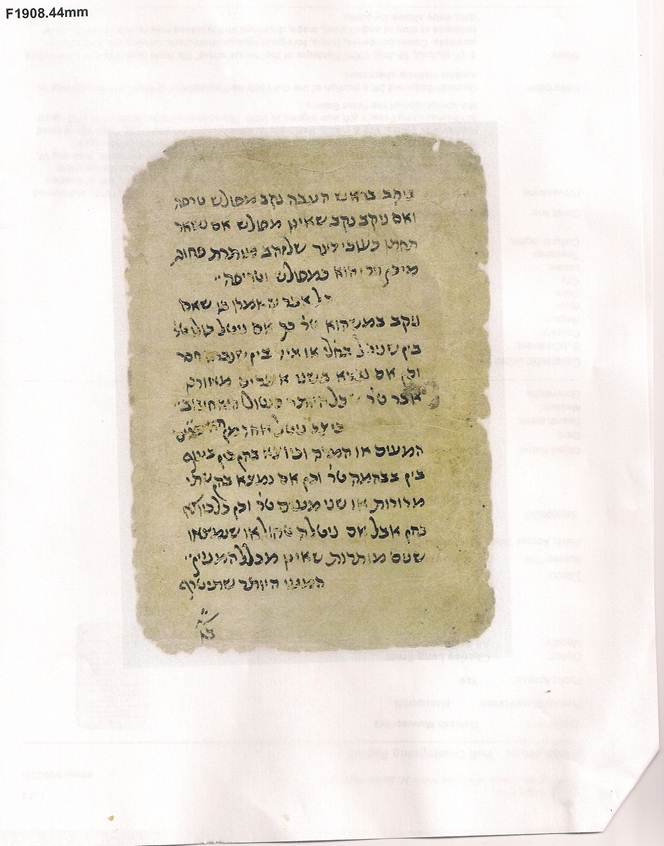

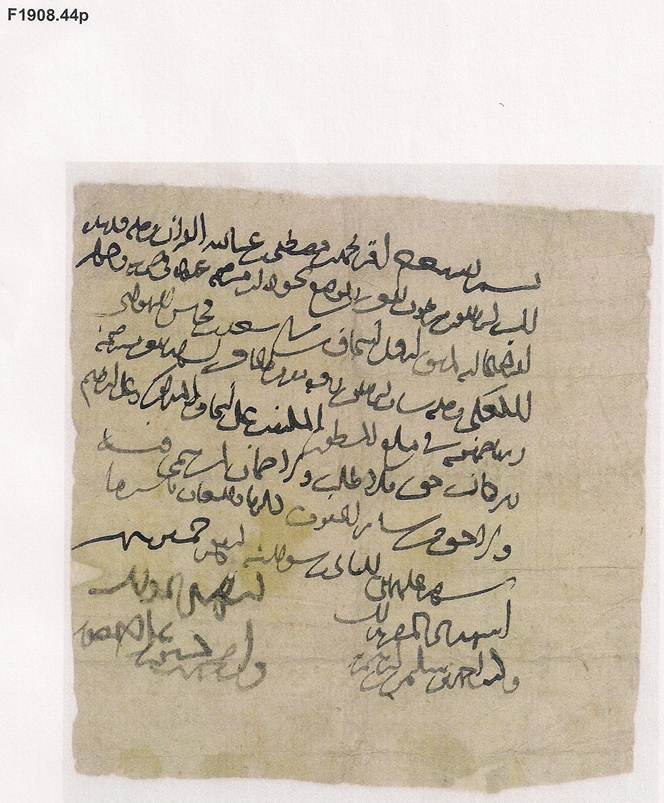

1. This is the third of three parts. These essays are based on the texts of three lectures, delivered as the Taubman Lectures at the University of California at Berkeley, in April 2010. We are grateful to Sasson Somekh for the opportunity to publish these in Sephardic Horizons. The illustrations are from Richard Gottheil and William Worrell, eds., Fragments from the Cairo Genizah in the Freer Collection, New York: Macmillan, 1927. With gratitude to Bension Varon and the Freer Gallery of Art.

2. Born in Baghdad in 1933 and immigrating to Israel in 1951, Sasson Somekh became an international authority on Arabic literature. Already an established poet in Arabic while in Iraq, he is the doyen of Arabic literary studies in Israel, having been one of the founders of the Arabic Department at Tel Aviv University, where he is now professor emeritus. He has published books and articles on the 1989 Nobel Prize-winning Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz and was also his close friend. An early work, The Changing Rhythm: A Study of Naguib Mahfuz's Novels (1973) helped establish Mahfouz's reputation internationally. Somekh is also among modern Hebrew's most respected translators of contemporary Arabic poetry. His two latest books are Mongrels or Marvels: The Levantine Writings of Jacqueline Shohet Kahanoff , ed. Deborah Starr and Sasson Somekh (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2011,which Yael Halevy-Wise reviewed in the Winter 2012 issue of Sephardic Horizons, and Life after Baghdad: Memoirs of an Arab-Jew in Israel, 1950-2000 (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2012).