The Taranto-Capouya-Crespin Family History: A Microcosm of Sephardic History

By Leon B. Taranto1

© June 11, 2011

Part II. The Capouya, Crespin and Bonomo Families

Leah and her Capouya-Crespin-Bonomo Family

Leah Capouya Taranto

In the 1880s, Bension married Behora Leah Capouya in Rhodes. Leah2 was born in Rhodes, probably in the late 1860s.3 Her father Raphael Sabetay Capouya (MeCapouya)4 of Rhodes was the son of Eliahu Capouya and Rachel Capelluto.5 Leah’s mother was Mazaltov (Fortuneé) Crespin (Crispin) of Izmir, then called Smyrna or Smyrne. Mazaltov's father was Yehuda (Leon) Crespin (Crispin) of Izmir, a banker, and head of a long-prominent rabbinical family.

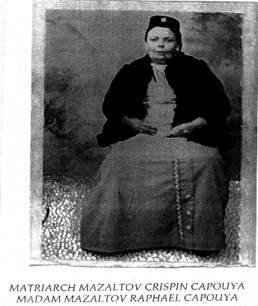

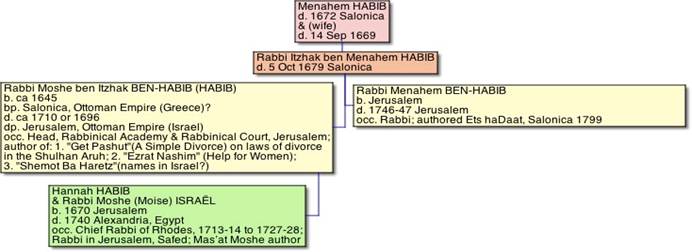

Mazaltov Crespin Capouya

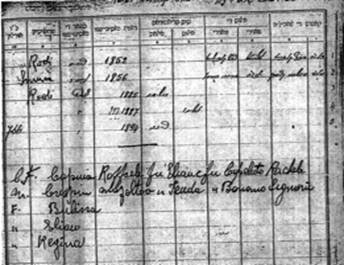

The Rhodes Jewish Community census conducted by Italian officials in 1938 identifies “Masaltov Crispin,” wife of “Raffaele Capuia” and born on March 15, 1846 in Smirne (Izmir), as the child of Leon Crispin and Signoru Taranto, both deceased. Masaltov and Raffaele wed in Rhodes on January 26, 1866. Another Rhodes census entry identifies Mazaltov (b. 1856 Smirne) as the daughter of Jeuda Crispin and, more accurately, Signura Bonomo. Cemetery data from Izmir identifies Mazaltov's father Leon (Jeuda) as Yuda Crespin (d. 1885), son of Mazaltov. Israeli genealogist Dov Cohen confirms the 1885 death, and identifies Yehuda’s birth as 1812-13, based on an Izmir community census from 1845. Avraham Galante’s history of the Jews of Turkey identifies Leon (Juda) Crespin as a banker of Izmir.

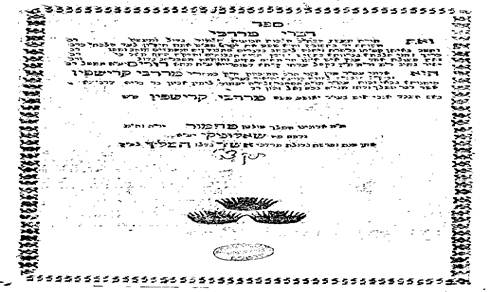

Mordehay Crespin, Dibrei Mordecai title page

According to Enrico Valvo, Consul for the Consolato d’Italia [Italian Consulate] in Izmir, our ancestor Yehuda Crespin appears in an 11 October 1871 Tuscan Register (for Tuscany in Italy) as Giuda Crespin, b. 1811 Smirne (Smyrna or Izmir), a banker who had come from Livorno (in Tuscany) and was then living in Izmir. Giuda (Yehuda) is identified as the son of Moise Crespin (who we know is Rabbi Yeoshua Moshe Mordehay Crespin, also called Moshe Crespin), and the husband of Signoru Bonomo, b. 1813 Smirne. The Tuscan Register also lists Giuda Crespin and Signoru Bonomo’s son Moise Crespin, b. 1851, Smirne, who would have been a brother to our matriarchal ancestor Mazaltov.6

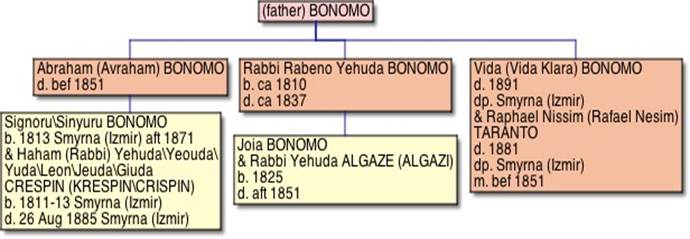

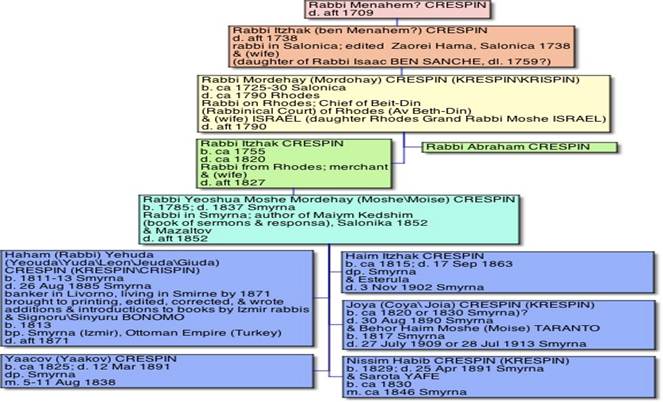

Signoru’s family name Bonomo is also confirmed by Dov Cohen’s discovery of an introduction by Rabbi Yehuda Algazi (b. 1825, d. after 1851) to the writings of his father-in-law Rabbi Rabeno Yehuda Bonomo, Matza Hen, published in Izmir, 1851. The first 38 pages were prepared by Rabbi Rabeno Elia Hakko, and the last 39 pages were by Rabbi Rabeno Yehuda Bonomo. Rabbi Bonomo's writing includes only two sermons, both marking the occasion of weddings. Reference is made to Rabbi Yehuda Algazi’s wife, daughter of Rabbi Rabeno Yehuda Bonomo (ca 1810-37), Rabbi Bonomo’s elderly brother Abraham Bonomo (d. before 1851), Abraham Bonomo’s unidentified daughter, and her husband Haham Shalem [complete sage] Rabbi Yehuda Crespin (d. before 1851), and Rabbi Algazi’s mother’s brother Rabbi Elia Hakko. From this, we know our ancestor Yehuda Crespin married Abraham Bonomo’s daughter.

Capouya Crespin family in Rhodes Italian census

Dov Cohen reports that Yehuda Crespin’s father, called Moshe Crespin in the 1845 census of the Izmir Jewish community, was Rabbi Yeoshua Moshe Mordehay Crespin, 1785-1837, author of Maiym Kedoshim, a book of sermons and responsa, printed in Salonika 1852, after his death. Born on Rhodes in the 1840s or as late as 1850, Raphael Capouya died in 1936-37. His wife Mazaltov Crespin reached her 90s and died around 1940-41. Both are buried on Rhodes,7 in the “new” cemetery that the tiny Jewish community on the island still maintains.8

Rabbi Dov Cohen of the Ben Zvi Institute in Jerusalem, a descendant of another Crespin rabbinical family of Izmir, traces the ancestry of our Haham Yehuda Crespin (b. 1812-13, d. 1885) to the prominent Rabbi Mordehay Crespin (Krespin) of 18th century Rhodes, head of the Bet Din (rabbinical court). Yehuda’s father Rabbi Yehoshua Moshe Mordehay (Moshe/Moise) Crespin (b. 1785, d. 1837 Smyrna) was the son of Rabbi Itzhak Crespin (b. ca 1755, d. ca 1820), a rabbi from Rhodes and a merchant. Itzhak’s father Rabbi Mordehay Crespin (ca 1725-1790) authored two important responsa, or rabbinical texts, published in early 19th century Salonika after his death. Rabbi Marc Angel, in his history of The Jews of Rhodes9, pp. 58-59, 66-71, 166-67, 169-70, 185-86, cites the responsa of our ancestor Mordechai Crespin (“Krespin”) of Rhodes – Maamar Mordecai, Salonika, 1813, and Dibrei Mordecai, Salonika, 1836 – and identifies Crespin as the son-in-law of Mosheh Israel, Grand Rabbi of Rhodes, which Dov Cohen confirms.

Israel Rabbinical Dynasty of Rhodes and the Levant

Our ancestor Rabbi Moshe Israel was one of the leading luminaries of the Sephardic world in the early 1700s. He founded the famed Israel rabbinical dynasty of Grand Rabbis who served Jewish communities in the eastern Mediterranean for the next two centuries, including Cairo, Alexandria, Rhodes and Jerusalem, and as rabbis for communities in Ancona (Italy) and Craiova (Romania). The dynasty continued until the death of his descendant Reuben Eliyahu Israel (1856-1932), the last Grand Rabbi of Rhodes, knighted by King Victor Emmanuel of Italy.10

Bonomo Family Tree

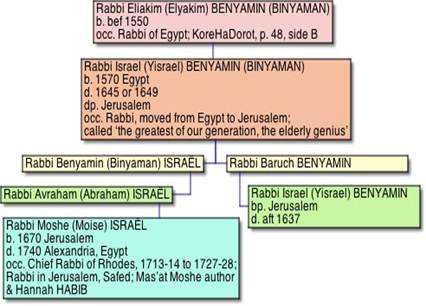

Israel (Benjamin) rabbinical family, 1500s to 1700s

Rabbi Moshe Israel (1670-1740) was from a rabbinical family. His father Rabbi Avraham Israel was a son of Rabbi Benyamin (Binyaman) Israel; son of Rabbi Israel Benyamin (Binyaman) who was born in Egypt about 1570, and moved to Jerusalem in old age, where he died around 1645 or 1649 in Jerusalem; son of Rabbi Eliakim (Elyakim) Benyamin (Binyaman) of Egypt, who lived in Cairo in the 1500s. Moshe Israel served as Grand Rabbi for Rhodes from 1714 to 1727, after he accepted a lifetime appointment.11 Obtaining a release from the commitment, he resumed his prior role as emissary for Israel’s Jewish communities. Before moving to Rhodes, Rabbi Israel was dispatched by the Jews of Safed to Morocco to collect monies for their community. Returning from Rhodes, he became an emissary for the Jerusalem community, representing them on a mission to Italy in 1731. He authored the responsa Mas’at Mosheh, published in Constantinople (Istanbul) in 1735. He died in 1740, in Alexandria, Egypt.

The wife of Rabbi Moshe Israel (1670-1740), our ancestor Hannah Habib (Ben-Habib) was the daughter, and only child,12 of Rabbi Moshe Habib (Ben-Habib), head of the rabbinical academy in Jerusalem three centuries ago.13 Born in Salonika circa 1645, Rabbi Moshe Ben-Habib died around in Jerusalem 1710.14 He was the son of Rabbi Itzhak Ben-Habib, who died in Salonika around 1680.15 Itzhak’s father was Rabbi Menahem Ben-Habib, who died in Salonika in 1672.16

Rabbi Moshe Israel (1670-1740) had three sons who also were rabbis: Yitzhak (Isaac) Israel; Hayyim Abraham Israel, b. 1708, Rhodes, d. 1785, Ancona, Italy, who was a rabbi in Alexandria;17 and Reuben Eliyahu (Eliyahu) Israel, b. 1710, Jerusalem, d. 1784, Cairo, Chief Rabbi of Alexandria ca 1772-84.18 For another two centuries, the Israel family produced many illustrious rabbis, such as Moshe Israel (d. 1802), Chief Rabbi of Alexandria, 1784-1802; Moshe (Moses ben Eliyah) Israel (1748-82), Chief Rabbi of Rhodes until his death in 1782; Haim Yehuda (Judah) Israel (1768-1829), Chief Rabbi of Rhodes, 1815-20; Michael Jaacob (Mikhael Ya’akov) Israel (1790-1856), Chief Rabbi of Rhodes, 1821-55, Raphaél Yitzhak Israel, Chief Rabbi of Rhodes up to 1882; Rahamim Haim Yehuda Israel (1815-92), Chief Rabbi of Rhodes, 1882-92; and Reuben Eliyahu Israel (1856-1932), the last Chief Rabbi of Rhodes, 1921-32.19 My genealogical trees showing the rabbis of the Israel-Crespin family appear at: www.rhodesjewishmuseum.org/history/the-rabbis-of-rhodes

Rabbi Itzhak Crespin in Zaorei (Zahore)

Hana, title page, 1738

Crespin Rabbinical Dynasty: Salonika, Rhodes, Izmir

Our ancestor Rabbi Mordehay Crespin (ca 1725-90), son-in-law to Rabbi Moshe Israel (1670-1740), was the son of Itzhak Crespin – apparently the same as Rabbi Itzhak Crespin ben Menahem who had “rabbinical actuation in Salonika” in the 18th century.20 Rabbi Itzhak ben Menahem Crespin edited the book Zaorei (Zahore) Hama, published in Salonika, 1738. The image displayed here, from Rabbi Dov Cohen, is the title page of the book with an inscription by Avraham Miranda (Meranda) saying he received the book from his uncle Itzhak Crespin. Also, Dov Cohen quotes an article by Meir Benayahu,21 “Hatena Hashbetait Besaloniki” [The Sabbatean Movement in Salonika],22 saying “cabalist Rabbi Itzhak ben Menahem Crespin” was the uncle of Rabbi Avraham Miranda, called Behor (b. 1723 in Salonika).

The line of descent from Rabbi Mordehay Crespin (ca 1725-90) to Leah Capouya’s mother Mazatov (Fortuneé) Crespin (wife of Raphael Sabetay Capouya) is, as previously mentioned, through a series of rabbis. Mordehay’s son was Rabbi Itzhak Crespin from Rhodes, b. ca 1755, d. ca 1820. Itzhak’s son was Rabbi Moshe Yeoshua Mordehay Crespin (known as Moshe), b. ca 1785, d. 1837, author of Mayim Kedoshim, a book of sermons and responsa, printed in Salonika in 1852. The 1845 census for the Jews of Izmir shows Moshe’s son Yehuda Crespin as Haham Yehuda b[en] Moshe Crespin, age 32 (born 1812-13).23

The 1845 Izmir census, supplemented to 1850, lists only males, with Yehuda Crespin’s sons, but not daughter Mazaltov (Fortuneé), who wed Raphael Capouya (Leah’s parents). Yehuda’s sons (Leah’s uncles) were Mordehay (age 10 in 1845), Elia (age 6, d. before 1850), Avraham (4), Shelomo (1) and Moshe (age 1 in 1850).24 Another record from Dov Cohen identifies daughter Devora (Debora) Crespin, b. ca 1845, who on 23 Nov. 1860 wed Yaacov (Yaacob) Bonomo, b. 1844, son of Tchelibi Shalom Bonomo, b. 1809, in Izmir’s Algaze synagogue.

Like several of their Crespin ancestors, both Yeoshua Moshe Mordechai (aka Moshe) Crespin and his son Yehuda Crespin, were prominent and well-published rabbinical authorities, and eulogized after their deaths by other rabbis. Dov Cohen has compiled documents from these books and eulogies that provide rich details concerning our Crespin ancestors Yehuda Crespin and his father Yeoshua Moshe Mordechai Crespin.

In 1822, Leah Capouya’s great-grandfather Yeoshua Moshe Mordechai (Moshe) Crespin, signed his name Moshe Mordechai Crespin to a document for the will of the sick Menahem Barmaimon. Menahem and his wife Simha Caden had no children. Menahem named as a benefactor his nephew Rahamim Barmaimon, engaged son of his deceased brother Haim. Over a century later, in 1939, Rahamim’s great-great-granddaughter Bette Papouchado wed Moshe Crespin’s great-great-grandson Morris Taranto, joining the families. The Ben-Zvi Institute archives contains a Responsa manuscript by Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Crespin, from about 1825, with his autograph.

Crespin rabbinical family, 6 generation chart

In 1828, Rabbi Moshe Crespin, now called Yeoshua Moshe Mordechai, brought to publication, in Salonika, the book Marmar Mordechai, written by his grandfather Rabbi Mordechai Crespin of Rhodes. In the book’s introduction, Yeoshua Moshe Mordechai writes that his father Rabbi Itzhak Crespin was not only a rabbi, but also had an occupation as a merchant to support his family and himself. Yeoshua Moshe Mordechai writes also of a dream that he was entrusted with his father’s writings, but had no money for that. Then someone told him that they had the same dream, and gave him money for publishing the writings. Yeoshua Moshe Mordechai gained also money from his mother, who sold her jewels, and from four other donors, brothers Haim Moshe Taranto and Efraim Taranto (Bension’s great-grandfather), cousin Raphael Moshe Israel from Rhodes, and Moreno Pessahia Ben-Habib. About sixty years later, Yeoshua Moshe Mordechai’s great-granddaughter Leah Capouya married Leon Bension Taranto, strengthening the long-standing ties between the Crespin and Taranto families.

In 1832, Moshe Crespin signed a rabbinical document on the legacy of Raphael Avraham Yahini as Rabbi Yeoshua Moshe Mordechai Crespin. Yeoshua means “salvation” and, proposes Dov Cohen, was likely added by Moshe Crespin on account of an illness suffered between 1822 and 1832. His name appears again as Rabbi Yeoshua Moshe Mordechai Crespin, after his death, in a eulogy sermon Rabbi Shelomo Hakim gave on October 7, 1838, and published in his book Heshek Shelomo, Salonika 1847. Calling Rabbi Crespin his “right hand,” Rabbi Hakim lauds his “wisdom, knowledge and integrity.”

Rabbi Yeoshua Moshe Mordechai Crespin’s eldest son, Leah’s grandfather Rabbi Yehuda Crespin, edited and brought important rabbinical works to publication. One book was Yelo Od Ela, by Rabbi Eliahu Ha-Cohen of Izmir, published in Izmir, 1853. In his introduction in the book’s first pages, Rabbi Yehuda Crespin mentions that despite being very occupied working in his store and traveling out of the city, he continues his Talmudic and Torah studies, correcting and preparing this book to be published. Yehuda Crespin recounts that one time when he was out of the city, a fire burned his store; Yaacov Abulafia entered to save the manuscript.

In 1867, Rabbi Yehuda Crespin corrected and brought to printing the book Yado Bakol, published in Izmir. His introduction title “Hakdamat Ha-Magiah H-YaKaR” means introduction of the corrector ha-yakar. YaKaR” is the abbreviation for his name, Yehuda CRespin; in Hebrew, yakar means ‘dear’. Rabbi Crespin says his writings were burned in the great fire of 11 Av 5601 (1841); and he is always occupied working to support himself and his family.

Yehuda Crespin is mentioned by his nickname Y(a)K(a)R also in Rabbi Eliahu Behor Hazan’s introduction to his grandfather Rabbi Haim David Hazan’s book Ishrei Lev, published in Izmir, 1869. Rabbi Yehuda Crespin is noted for his eulogy to the author, of whom he was a disciple. Rabbi Crespin’s eulogy to Rabbi Haim David Hazan appears at the end Ishrei Lev, recounting that corrector haYaKar gave the sermon in the Etz Hahaim Synagogue, thirty days after the death of his master Rabbi Haim on 5 Shevat 5629 (17 Jan. 1869). Rabbi Crespin mentions his visit to his master in Jerusalem that same year, 1869, and his eleven-day stay in the Land of Israel.

The last three documents are eulogies to Rabbi Yehuda Crespin. In an 1886 publication, in Izmir, Rabbi Avraham Palatche writes of his eulogy sermon for Rabbi Yehuda Crespin, given 12 Sep. 1885 in the Algaze Synagogue. Rabbi Palatche writes of Yehuda Crespin: “his soul loved the Torah and he did not wish to be dependent on others:” he would “use his wisdom and knowledge in the Torah” to “maintain himself [as an official rabbi], so he was also fatigued to search his own support, and he was very pious, and at this end unfortunately he did not speak.”

In a second eulogy, preserved in Derisha Mehaim, published in Izmir, 1888, Rabbi Nissim Moshe Modai writes of the sermon in the Talmud Torah Synagogue in 5646 (1885), to “Rabbi Yehuda Crespin, beloved as a brother of mine.” Modai described Crespin as “G-dfearing” and “devoted to the perfect practice of Torah precepts.” He was a “member of the Hevra Kadisha of Bikur Holim [visiting the moribund] with love and a special devotion. Despite he was occupied in working for his sustain [sustenance] with wares and traveling for that in dry land and through the ocean, bringing livelihood to his family, without ... dependence on other[s], nevertheless the Torah was saved in his heart and Torah books were always found in his hands. He learned at his home, and also during the day, when he had a free time he used it to learn and study. At the last time he moved from the city to be more free to learn but he did not reach that because he became ill with Tifa [typhus?] and he suffered a lot, mainly because he was unable to speak....”

A third eulogy to Rabbi Yehuda Crespin was delivered by Rabbi Itzhak Crespin, of a different Crespin family - from which Dov Cohen descends - and is preserved in Itzhak Crespin’s book Shemo Itzhak, published in Izmir, 1893. Itzhak Crespin writes of the Shabbat sermon he gave on the death of Yehuda Crespin, of blessed memory. After “the death of this ‘tzadik’ [righteous man] we have the obligation to cry and also because that in his life he tried so much to make ‘aliyah’ and go to live in the Land of Israel, but unfortunately he did not reach that...”

A rabbinical document from 1863, regarding a controversy between members of the Levy family of Izmir, was signed by eight board members of the Jewish community of Izmir, including Rabbi Yehuda Crespin’s brother Nissim Habib Crespin and a David Taranto, probably the David Taranto (b. ca 1827) who was the uncle of Leon Bension Taranto. Yehuda’s sister Joya (Coya) (b. ca 1820-30, d. 1890) wed Behor Haim Moshe Taranto (b. 1817, d. 1909-13), joining the Crespin and Taranto families almost fifty years before Leah married Bension.

Capouya Family of Rhodes

Leah’s father Raphael Capouya apparently had four brothers - Jacob (Yaacov or Giaccobe), Abraham, Haim (Victor), and Joseph - and four sisters - Miriam, Leah, Rebecca and Mazaltov).25 Haham Yaacov Capouya (Capuya) served as Rabbi for the largest synagogue on Rhodes, the Kahal Kadosh Gadol (Kahal Grande).26 Their descendants emigrated widely, settling largely in southern Africa, Latin America (Argentina, Columbia, Paraguay, Panama), France, Belgium, and the United States (e.g., New York, Atlanta, Montgomery, Miami, Memphis).

On Rhodes, Raphael was a bookkeeping consultant to banks and an exchanger of foreign currency, which perhaps played a role in his marriage to Mazalto (Mazeltov/Fortuneé) Crespin, daughter of banker Haham Yehuda (Yeouda/Yuda/Leon/Jeuda) Crespin/Crispin/ Krespin (1812-87) of Izmir. Raphael’s “family was considered as middle to upper-class under Turkish rule.”27 An educated man, he owned and operated a currency exchange.28 Behora Leah Capouya, Bension's wife, was the first of Raphael and Mazaltov’s nine children.29 The other eight, likely in order, were Nissim Raphael (wed to Esther Rousso), Sarota/Sarah (wife of Ascer/Asher Charhon), Isaac (husband of Estherina/Ester Menashe/Menascé), Albert/Abraham, Boulissa (divorced from Chilibon Capilouto), Catherine (wife of Bahor Hasson), Eli (wed to Leonora/Louna Alhadeff), and Reina/Regina (wife of Isaac Menashe/Menascé).

Raphael Capouya 1922 Italian notarization

The Capouya children eventually left Rhodes, except Albert (Abraham), who died of typhoid fever (or typhus?) around age 20-21. Most had the good fortune to leave before the Nazi conquest. Sarota and Ascher Charhon settled in France. Leah’s three remaining sisters eventually settled in South America with their husbands. Buenos Aires became home to Boulissa and Chilibon Capilouto, and Reina and Isaac Menashe. Catherine and Bahor Hasson moved to Brazil. Two of Leah’s brothers, Isaac and Eli moved to Montgomery. Nissim, his wife Esther Rousso were among the Jews deported by the Nazis from Rhodes and killed at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Their daughter Dora was one of the few survivors.30

Voyage of the Saxonia

On August 21, 1912, the vessel S.S. Saxonia steamed out of Trieste at the northern end of the Adriatic Sea. Now an Italian city on the Slovenian border, Trieste was then the principal port of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. As the Saxonia headed for America, on board were “Lea Taranto,” recorded age 40,31 and her seven youngest children, the last members of the Leah and Bension Taranto family to leave Europe and Asia. The ship manifest lists the children as “Katina” (Catherine), age 15 (13 if the handwritten record is so deciphered); “Diana” (Esther), age 11; "Yontof" (Yom Tov),32 age 9; “Judith” (Julia), age 8; “Abram” (Al), age 6; "Moys" ("Moise" or Morris), age 4, and “Elisa” (Alice), 2 and 1/2 years.33 All were immigrating to join Bension and the four oldest Taranto children -- Sultana, Ephraim, Sadie, and Joseph (Joe). En route to New York, the Saxonia picked up more passengers in Fiume (Rijeka, Croatia) on August 24, at Patras (Greece) on the 26th, in Naples on the 28th, and Gibraltar on September 1st.

Raphael Capouya gravestone, 1936

It might seem odd that the Tarantos boarded in distant Trieste, a 1000 mile journey from Rhodes, rather than Patras, only 350 miles away. Could Leah have boarded in Trieste to secure her family a place on the vessel? By the time the Saxonia would reach Patras, passenger space might be limited, with preference given to native Greeks. Also, Turkey and Greece were at war in 1912. Another reason for boarding in Trieste might have been potential dangers for Jews in Greek-ruled Patras. The Peloponnesus peninsula of southern Greece (Morea), where Patras is located, had been the home of Jewish communities for millennia, from Roman times. By 1820, more than 5,000 Jews inhabited these communities, a blend of Sephardi, Italian, Ashkenazi and native Romaniote Jews. In 1821 the Greeks rebelled against their Ottoman overlords, eventually winning independence with British, French and Russian support. While poet Lord Byron lionized the Greeks, their war for independence was catastrophic for Peloponnesian Jewry. Most were slaughtered at the outbreak of hostilities. Ancient Jewish communities in Patras, Sparta, Corinth, Thebes and elsewhere were wiped out.34 Sephardim from Rhodes in 1912 could reasonably fear travel to the Peloponnesus, where no Jewish communities survived.

On September 12, the Saxonia steamed into the Port of New York, reuniting the Tarantos for a new life in America. The Statue of Liberty welcomed them with the inscribed verses of Sephardi American poet Emma Lazarus: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses, yearning to breathe free.” How fitting that the Tarantos leaving the site of the ancient Colossus of Rhodes were greeted by Lazarus' sonnet “The New Colossus”! Our ancestors’ fateful decision to emigrate rescued us from the Shoah that a generation later annihilated Jewish communities in Rhodes, virtually all of Greece, and most of Europe, including some Capouyas and Tarantos.

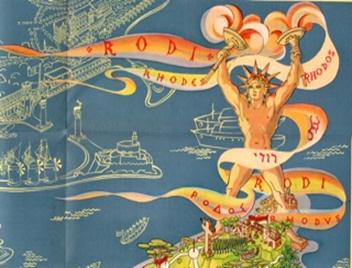

Colossus of Rhodes, 1930s Hebrew-Italian travel

The Arriving Immigrants

The Saxonia ship manifest lists Leah and her children as Turkish nationals from the Isle of Rhodes, their birthplace. The “nearest relative(s)” left behind in Rhodes are Leah's “parents Raphael Kapouyian” (Capouya). Their final destination is Montgomery, to join Leah's “husband [Bension and son-in-law] Salomon Rousso,” now wed to Leah’s daughter Sultana. The manifest notes their “good” health. Young Moise’s “good health” entry came only after the strong intervention of his teen-age sister Katina (Catherine). When the Saxonia docked at the Port of New York, government officials examining the immigrants thought something was wrong with Morris’ eyes and, as the legend goes, considered sending the whole family back to Europe. Catherine’s quick thinking changed their minds. She explained that Morris' eyes were red because he's always crying. Her powers of persuasion prevailed and the Tarantos were allowed entry to America.

Leah's recorded height is 5 feet 4 inches; Katina is 5 feet. Curiously, the complexion for all is noted as "dark" though most were very faired-skinned.35 Their hair and eyes are described as brown. The five oldest children -- Katina (Catherine), Diana (Esther), Judith (Julia), and Yom Tov -- can read and write, but not Leah.36 While "Hebrew" is the listed "race or people" for other Sephardim on board, Leah and her children are classed as "Turkish."37

The Montgomery Pioneers

In February 1912, the Montgomery brit milah of Morris Rousso celebrated the birth of our first family member in the New World. He was Leah and Bension’s first grandchild, son of Sultana and her husband Solomon Rousso. Bension Taranto attended the brit, with his four eldest children: Sultana of course, and Ephraim, Sadie, and Joe.38 On November 17, 1912, only a few months later, Sadie married Ralph Cohen in Montgomery’s first Sephardic wedding.39 Six years earlier, Ralph had become the first Sephardi to settle in Montgomery.40 By 1910, the first Tarantos settled in Montgomery. Sultana’s husband Solomon operated a fruit business at 229 1/2 Commerce Street, only feet from his residence at 221 Commerce.41 Ephraim Taranto, the second-born Taranto child, was lived in Montgomery, and presumably Joe. Ephraim, Joe, and their brother-in-law Solomon would pave the way for the rest of the family to come to America. Sultana and Sadie arrived in 1911 with Bension. The rest of the family came the next year.

Taranto family at Brit Milah of Morris Rousso, Montgomery 1912

By 1910, Ephraim was a clerk for Steiner & Lobman,42 in the wholesale dry goods industry.43 According to the April 1910 Census records, Ephraim, age 18, was an unmarried “lodger” at the residence of Michael Spencer (age 79) at 31 Sayre. Spanish is the native tongue for Ephraim and his parents. Ephraim can also speak English, read and write.44 Living at the same address was an older Taranto boarder, an unmarried male age 25, whose first name appears to be “Misaur” or “Nissur” (perhaps Nissim) in the handwritten census record. Emigrating from Turkish Europe in 1908, he speaks his native tongue of Spanish, and works as a shoemaker in his own shop.45

In 1911, Ephraim, still working at Steiner & Lobman, now resided at 20 Wilkinson.46 The City Directory lists him as “Toranto” rather than “Taranto.” By 1912, “Bension Taranto” was living in Montgomery, working as a “clerk” at 514 Monroe.47 In 1913, Solomon Rousso was operating a delicatessen business, “Rousso, Capouya & Co.,” at 207 Montgomery and 103 Dexter Avenue. Other principals in this business included I. Menashe (possibly Isaac Menashe, who married Leah’s younger sister Reina and eventually settled in Buenos Aires), E.B. (Ephraim B.) Taranto, E.R. Capouya (presumably Leah’s brother Eli), and Joseph Capouya.48

By 1913, the Taranto’s relocated to 430 Sayre in Montgomery, the listed residence for B. (Bension) and Leah “Toranto,” Solomon and Sultana Rousso, Ephraim B. “Taranto,” Joseph “Toronto,” B.J. (Bension?) “Toranto,” and Eli R. Capouya, and business of Esther “Toranto.” Joseph “Toranto” operated a clothes cleaners at 520 Dexter, also the site of B.J. (Bension?) “Toranto’s” fruit business.49 Bension also sold candy, cigars and drinks. Joseph Capouya, at 31 Sayre (Ephraim’s home in 1910), lived only a few blocks from the Taranto home.50

Settlement in Atlanta

After living for a few years in Montgomery, Leah and Bension moved their family to Atlanta, joining its growing Sephardic community. Among the Sephardi pioneers already in Atlanta were the Papouchado brothers, Victor and Sam, originally from Izmir. Two decades later, in August 1939, Leah and Bension’s youngest son, Dr. Morris Taranto, would marry Victor’s eldest daughter Bette, born in Atlanta in September 1914 as Rebecca Papouchado.

Census records provide a snapshot of the family shortly after arriving in Atlanta. On January 5, 1920, a census official recorded his visit that day to the “Benseon Taranto” family home at 222 Central Avenue. The household included “Benseon,” age 65 (born circa 1864); his wife Leah, age 44 (b. ca. 1875); daughter Sadie Cohen, age 25 (b. ca 1894); “daughter” Victoria Taranto (presumably either son Ephraim’s wife or Bension’s niece), age 18 (b. ca. 1901), sons Abraham (Al) Taranto, age 14 (b. ca. 1905), and Maurice (Morris) Taranto, age 12 (b. ca. 1907); and grandson Nese (Nace) Cohen, age 6 (b. ca. 1913), Sadie’s son. All were born on Rhodes, except Nese, born in Montgomery. Rhodes is also shown as the birthplace for the parents of both Bension and Leah (though Bension’s parents and Leah’s mother were actually from Izmir).51 Bension and Leah do not speak English, but all of their children do. The census does not list Yom Tov, who died in 1917, and curiously omits Alice.52

Living in Atlanta, Bension opened a soda fountain/ice cream parlor with his cousin Eli Franco. The 1920 Census identifies Bension’s as a “salesman” in a “soda” store or the ”soda” industry. He later sold his interest in the business to his partner Eli and opened a small grocery store at Crumbley and Pryor Street, near the Taranto family’s Central Avenue home.

Blessed with long life, Leah and Bension saw nine of their children marry and raise families. Their final home was at 535 Parkway Drive, northeast Atlanta. On May 1, 1950, “Leon Benson Taranto” died in a private hospital in Atlanta, reportedly at age 92.53 About four months later, July 28, 1950, Leah died at age 82, survived by brother Isaac Capouya of Montgomery, three sisters – Sarah (Sarota) Shahon (Charhon) of Paris, and Mrs. Isaac (Reina) Menasche and Mrs. Boulissa Capilouto, both of Buenos Aires, four sons (Ephraim, Joe, Al, Morris), three daughters (Catherine Galanti, Sadie Yohai, Julia Pinto), over two-dozen grandchildren, and 11 great-grandchildren.54 Their 30th and final grandchild arrived eight months later, and ultimately over 160 great-, great great-, and great-great-great grandchildren.

Alice Taranto, ca. 1927

Family Tragedies

Losing a child is for many the ultimate tragedy, as it was in Biblical times.55 Leah and Bension experienced the heartbreak of losing four children. In 1917, while the Great War raged in Europe and successive revolutions toppled the Russian Czar and his democratic successors, Yom Tov died around age 14-16. Three years later, on April 12, 1920, Sultana died, survived by husband Solomon and their two young children.

On March 4, 1933, millions of Americans celebrated Franklin Delano Roosevelt's inauguration as President, with the promised New Deal. For the Tarantos, this was instead a day of personal mourning; Alice, at age 22 the youngest of the children, was pronounced dead at Atlanta’s Grady Hospital. The city newspaper’s front page reported that she swallowed a deadly poison early that morning at the meat market where she worked.56 On July 11, 1945, Leah and Bension lost yet another child, this time Esther (Mrs. Morris Capouano), survived by her four children.

Aspiring to Citizenship

By the 1920s, the Tarantos moved toward U.S. citizenship, filing naturalization petitions and declarations of their intention to renounce allegiance to the Italian king who ruled Rhodes. On April 13, 1925, Abraham (Al) Taranto, declared his intention to renounce Italian citizenship and become an American. Al was an unmarried student living at 321 Central Avenue in Atlanta. Then age 19, Al reported his birthdate as December 23, 1906. If already 19, his actual birth date was more likely December 1905. While Al listed “Martha Washington” as the vessel carrying him to America, the ship manifest records show he was aboard the Saxonia. If unable to recall the vessel’s name, he might have borrowed the name “Martha Washington” from the vessel carrying his father and sisters Sultana and Sadie. The Declaration identifies Al as a student with black hair, brown eyes, dark complexion, 6 feet 1 inch tall, and weighing 155 pounds.57

On June 2, 1926, Ephraim declared his intention to renounce Italian citizenship and become a U.S. citizen. He was a restaurant keeper, age 35, 5 feet 10-11, 165 pounds, with black hair, grey eyes, and dark complexion, living at 455 S.W. Central Avenue in Atlanta with his wife Victoria, who was born in “Constantinople, Italy.”58

By the early 1940s, family members entered the United States Armed Forces to defend our country. Among the first was Leah and Bension’s youngest son Morris. Enlisting in the Army, he served as a physician in war ravaged England and France, rising to Captain.

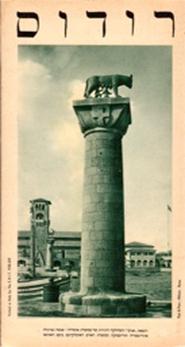

Rhodes harbor, 1930s,

Hebrew travel map

Our Rhodeslis Heritage

Rhodes, where Bension and Leah were born, is the largest Dodecanese isle. Located off Turkey’s southwest coast and now part of Greece, Rhodes was a central part of the Ottoman Empire. As the Tarantos left for America, the Empire was disintegrating. In 1912, Italian troops occupied their native Rhodes, ending four centuries of Turkish rule; and Greece annexed Epirus and the predominantly Jewish city of Salonica, the Jerusalem of the Balkans.59 Serbia and Bulgaria pushed into Macedonia; Albania declared independence.

Two thousand years earlier, Rhodes was the site of the fabled Colossus, the Seventh Wonder of the World. As this towering statue spanned the opening of the city’s harbor (the Mandraki), ships sailed between its legs. In 75 B.C.E., only 67 years after its erection, the Colossus was toppled by an earthquake; it remained in the harbor for the next seven centuries.60 In 654 C.E., a general to Caliph Uthman stripped the Colossus of its bronze, taking the metal to Syria for sale to a Jewish merchant from Edessa, who carried it away atop the backs of 900 camels.61

Like fragments of the Colossus, Rhodes’ surviving Sephardim are scattered world-wide. On July 23, 1944, the Germans deported virtually the entire Jewish community to the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp. Of 1767 Jews on Rhodes and Cos at the time of the deportation, only 163 survived the war and Nazi death camps.62 Reviving the community after the war was not possible as few survivors returned. Today, only a handful of Sephardim remain on Rhodes.

Most Tarantos and Capouyas left Rhodes before Germany invaded. Some, however, tragically remained and perished after Italy surrendered to the small German invasion force. In addition to the family of Bension’s sister Behora, victims included Leah’s brother Nissim Capouya, his wife Esther Rousso, and other Capouya’s. Our Taranto-Capouya family are among the Sephardi remnants of Rhodes, a community of about 5,500 persons at its peak a century ago.63 Rhodeslis who survived are today dispersed globally, in the United States, Canada, Argentina, Columbia, France, Belgium, Italy, Greece, South Africa, Zimbabwe, and elsewhere.

This is the second part of a three-part series on Sephardic Horizons. Part one. Part three.

Photos & Images

- Leah Capouya (Mrs. Leon Bension Taranto)

- Mazaltov (Fortuneé) Crespin (Mrs. Raphael Capouya), photograph provided by Melvyn Halfon

- Rhodes Italian Census, 1920s, entry for Raffaele Capuia b. 1852, son of Eliau Capuia and Rachele Capeluto, wed to Mazaltov Crespin b. 1856, daughter of Jeuda Crespin and Signuru Bonomo

- Bonomo family chart

- Title page of book by Rabbi Mordehay Crespin, Dibrei Mordecai, Salonika

- Israel (Benjamin) family chart 1500s to 1700s - 5 generations

- Habib (Benhabib) family chart 1600s to 1700s - 4 generations

- Zaorei (Zahore) Hama, Salonika 1738, title page with inscription by Rabbi Avraham Miranda mentioning Rabbi Itzhak Crespin

- Crespin family chart

- Eliahu Capouya and Rachel Capeluto family chart

- Rafael Capuia document signed Aug. 1922 and apparently notarized by an Italian official, Rhodes Jewish Museum www.rhodesjewishmuseum.org/genealogy/resources

- Raphael Sabetay MeCapouya gravestone, Rhodes cemetery

- S.S. Saxonia

- Colossus of Rhodes astride harbor on a map of Rhodes, with Rodi in Hebrew, from 1930s Hebrew-Italian folder travel map for Rhodes

- Taranto family, February 12, 1912, Montgomery, Alabama, at Brit Milah of Morris Rousso, with parents Solomon Rousso and Sultana Taranto; Aunt Sadie Taranto (Cohen); Uncles Ephraim Taranto, Joseph Taranto, and Ralph Cohen; grandfather Leon Bension Taranto, and other family and friends

- Alice Taranto, high school graduation, ca 1927

- Rhodes harbor and she-wolf (symbol of Italy, replacing the stag) with Hebrew inscription “Rodos,” cover of 1930s Hebrew-Italian folder travel map for Rhodes

Notes:

1. Leon Taranto is a native of Atlanta and a Washington DC attorney who is active in Sephardic genealogy. He is an organizer and planning committee member for Vijitas de Alhad of the Greater Washington DC area. He has authored articles for Sephardic and Jewish genealogical journals on the Jews of the Ottoman Empire and Mediterranean Basin, and presented at international conferences on Jewish genealogy, to genealogical societies, and at synagogue-hosted events. For the extensive bibliography relating to this article, please see Part I in the previous issue of Sephardic Horizons, 1:4 (Summer-Fall 2011).

2. Leah, or ‘Lea,’ the name of Jacob’s first wife, like many Biblical names derives from an animal, here a ‘cow.’ Leyla Ipeker, “A Research on Names and Surnames,” Mosaic: Genealogy Research on the Jews of Turkey, no. 1, The Roots Committee, Istanbul 1996.

3. 11 The birth year traditionally ascribed to Leah is 1867, with 83 as her age at death. This roughly parallels her gravestone and contemporaneous newspaper reports of her July 1950 death. Both fix her age at 82, dating her birth to 1867-68. The late 1920s Italian census from Rhodes lists her birth year as 1864, while U.S. immigration and census records infer later dates. The ship manifest for Leah’s September 1912 arrival at the Port of New York reports her age as 40 years, placing her birth in 1871-72. Census data recorded on January 5, 1920, reports Leah’s age as 44 years, suggesting a circa 1875 birthdate.

4. The Hebrew inscription on the gravestone reverses the name order as Sabetay Raphael MeCapouya. Raphael was likely his given name, with Sabetay added to possibly signify his birth on Shabbat. Many Capouya gravestones, including Raphael's, can be viewed on the cemetery plots section of www.rhodesjewishmuseum.org

5. The Rhodes Jewish community census conducted in 1938 by the isle’s Italian rulers lists Raffaele Capuia (b. 1852 Rodi) son of Eliau and of Rachele Capelluto. Capuia is the Italian spelling, while. Capouya is a French variant. The Turkish spelling substitutes a ‘K’ for the Latin 'C,' resulting in ‘Kapuya,’ a name found in 20th century Izmir. The Hebrew form ‘MeCapouya’ or ‘MeCapua’ means ‘from Capua.’ The Capelluto (Capelouto) family was prominent on Rhodes, and lived also in Izmir, where the Turkish spelling ‘Kapeluto’ is seen. The Kapelutos of Izmir originated from Bodrum (ancient Halicarnasus), a port in the southwest corner of mainland Turkey, a few miles north of Rhodes. Stella Kent, "The Blend of Turkish Jews," Mosaic: Genealogy Research on the Jews of Turkey, no. 1, The Roots Committee, Istanbul 1996.

6. Consolato d'Italia - Izmir (Italian Consulate of Izmir), Enrico Valvo, Consul, “Email,” 19 Feb 2002, <izmir@italcons-izmir.com>, re 11 Oct 1871 Toscan Register entry for Giuda Crespin, b. 1811 Smirne, son of Moise, coming from Livorno, banker, living in Smirne; Giuda’s wife Signoru Bonomo, b. 1813 Smirne; son Moise Crespin, b. 1851, Smirne.

7. Capouya family histories provided by Dr. Morris Nace Capouya and Melvyn Halfon (1997) indicate that Mazeltov died in her 90's in 1940 or 1941, and Raphael in 1937 at age 96. Birth and death dates on Raphael’s gravestone appear to be 1850 and 1936.

8. In the late 1930s, the Italian Fascist governor, de Vecchi, forced the Jews to close the principal cemetery on Rhodes. With much agony, the Jews moved many gravesites to the present cemetery. As our Capouya cousin Herzl Franco explains, the governor wanted to build a road on the site of the old cemetery. Rebecca Amato Levy's vivid account of life on Rhodes identifies two other cemeteries, making four in all. Only the “new” one is maintained today. Levy, I Remember Rhodes, supra.

9. Marc D. Angel, The Jews of Rhodes: The History of a Sephardic Community, Sepher-Hermon Press, New York, 1978.

10. A review and chart of the Israel rabbinical dynasty is presented in the article by Leon Taranto, “The Israel Family – A Rabbinical Family 1670-1932,” La Lettre Sepharade, 20, 2005.

11. See Angel, The Jews of Rhodes; The Jewish Encyclopedia, Funk & Wagnalls, New York & London, 1904.

12. Personal communications with Lily and Isak (Ike) Arditi, 1999-2000.

13. Angel, The Jews of Rhodes; personal communications with Lily and Isak (Ike) Arditi, 1999-2000.

14. Personal communications with Dov Cohen, 2004.

15. Personal communications with Dov Cohen, 2004.

16. Personal communications with Dov Cohen, 2004.

17. Various works of Rabbi Hayyim Abraham Israel, eldest son of Rabbi Mosheh Israel, were published in Livorno in 1778 and 1786. Angel, pp. 169-70. Called ‘Rabbino de la Acqua,’ his prayers during a drought were answered with rain. Originally an Italian rabbi from Ancona and Candia (Crete), he lived in 18th century Alexandria, where his son Moses ben Abraham Israel was Chief Rabbi from 1784 to 1802. He wrote Bet Abraham (Livorno/Leghorn, 1786), a caustic commentary on the Tur Hoshen Mishpat and on the Bet Yosef thereto (at the end of the volume is a treatise Ma’amar ha-Melek on the laws of government); and Amarot Tehorot (1787), a commentary on Tur Eben ha-Ezer. Israel Mattithiah Terni quotes Rabbi Israel in his Sefat Emet (p. 73b, ed. Livorno/Leghorn). The Jewish Encyclopedia (Funk & Wagnalls, New York & London, 1894).

18. Reuben Eliyahu Israel (1710-84) was Chief Rabbi of Alexandria, Egypt from 1773 to 1784. Prior to and during his son Moshe’s appointment as Chief Rabbi of Rhodes, he lived on Rhodes. His works were published in Livorno (1792, 1806-07, 1828, 1830) and Salonika (1811, 1815). Eliyah Israel left two sons, Moses ben Eliyah Israel and Jedidiah Israel. He authored Ugat Eliyahu; Kol Eliyahu responsa; Kisse Eliyahu on the four Turim; Shene Eliyahu sermons; and Aderet Eliyahu commentary on Elijah Mizrahi.

19. Our information for the Israel rabbis is from multiple sources, many published and more unpublished. My extensive, delightful, and invaluable personal communications with Lily and Ike Arditi, and through them with others, warrant special mention. Without their contributions, it would have been impossible to construct the 17-generation family tree for the Israel, Ben-Habib and Crespin families of which our Taranto-Capouya family is a branch.

20. Personal communication with Dov Cohen, 2004.

21. A bibliography of Rabbi Benayahu’s publications, in Hebrew, is accessible online through the link at: http://manuscriptboy.blogspot.com/2009/07/meir-benayahu-bibliography.html

22. Sabbatai Zevi (Sabetay Sevi) (1626-76) is the mystic and kabbalist, whose Salonika family moved to Smyrna as it began to emerge as a major Jewish center. Gaining an international following throughout the Jewish world, Sevi proclaimed himself the Messiah. By age 40, he was forced by the Sultan to convert to Islam. Many of his followers, even after his death, followed him into Islam, spiriting a crypto-Jewish movement within Islam known as the Donmeh. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sabbatai_Zevi

23. Personal communication with Dov Cohen, 2004.

24. Personal communication from Dov Cohen.

25. Capouya family histories, supra.

26. As Rabbi Marc Angel reports, the Jewish cemetery on Rhodes contains a section with graves of rabbis, one of whom is “Israel Yaacob Kapuyah.” Angel, The Jews of Rhodes, p. 171 n.58. Rabbi Jacob Capouya’s grandson Herzl Franco recalls hearing that the Capouya family was of rabbinical origin.

27. Capouya family histories, supra.

28. Conversations with Herzl Franco (1997).

29. One would expect Leah, as a first born child, to be named for her father’s mother, Rachel Capelluto. Why wasn’t the custom followed? A plausible explanation might be that Leah was named for Raphael’s sister Leah, who could have died young or without children. Could it have been important for the Capouya's to preserve the name “Leah”? Or was Raphael’s sister “Leah” named for their grandmother?

30. Franco, The Jewish Martyrs of Rhodes and Cos, supra, pp. 87-88, 116.

31. Entry for Leah Capouya Taranto and Children, National Archives Microfilm Publication T-715, roll ___, Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, 1897-1942, from July 13, 1911 to ___, vol. 4318, p. 31, lines 11 et seq. Leah’s listed age of 40, if accurate, suggests a birth around 1872, rather than the 1860’s as we previously believed.

32. The handwritten ship manifest is difficult to decipher. Yomtov’s name appears as "Jousef" in the subsequently prepared typed soundex index in the National Archives.

33. Since the birthdates for Catherine, Julia, and Morris are after September 12th, their presumed birth years (based on their recorded ages at entry) are: Catherine, born 1896 (or 1898); Julia, born 1903; Morris, born 1907. Since the birthdates for Esther, Al, and perhaps Yom Tov and Alice are before September 12th, the presumed birth years derived from their ages upon entry to America are 1901 for Esther, 1902-03 for Yom Tov, 1906 for Al, and 1909-10 for Alice.

34. Stanford J. Shaw, History of the Jews of the Ottoman Empire and Turkish Republic, New York Univ. Press, 1991, p. 190.

35. Notation of their “dark” complexion might reflect either the notorious inaccuracy of records for the tidal wave of immigrants, or cultural and racial biases among recording officials. Or did officials have insufficient time to record all information for each immigrant and indiscriminately used ditto marks (“) to repeat information for the entire group. Thus, if a family head is “dark,” all other family members might be so described. In this manner, Moise’s (Morris) pale complexion could be misrecorded as “dark.”

36. Primary education became widespread among Sephardim of Rhodes only within the previous decade, with the founding of schools by the Alliance Israélite Universelle (AIU), in Paris. With able teachers like Mathilde Taranto (Bension’s niece, and daughter of his brother Isaac), AIU schools continued educating Jewish children in Rhodes through the 1930’s, including some of our Capouya cousins. See note 8, supra.

37. Other Rhodeslis boarding in Trieste were from the Berro, Capelouto, Kordoval, Emileh, Israel, and Benveniste families. New York was the destination for Mazelto (age 40) and Sarina Berro (14), Isaak Emileh (18), Victor Capelouto (18), Isaak Israel (19), and David Benveniste (20). Rebeka Kordoval (age 53), Mussani Capelouto (age 51), his wife Behora (41), and their children: Rebeka (age 15), Solomon (10), Jacob (8), ?Livson (6), ?Riccotta (1.5 years), and Labrates (3 months), were heading for Seattle.

38. A photograph of the celebrants - Morris Rousso, his parents Sultana and Solomon Rousso, grandfather Leon Bension Taranto, and his aunts and uncles, Sadie and Ralph Cohen, Ephraim and Joe Taranto (Toranto) appears at www.rhodesjewishmuseum.org/emigrate.htm

39. Yitzchak Kerem, “The Settlement of Rhodian and Other Sephardic Jews in Montgomery and Atlanta in the Twentieth Century,” American Jewish History, Dec. 1997, pp. 373-391, at p. 375 n.8, www.sephardicstudies.com/atlanta.html citing Congregation Etz Ahayem, Tree of Life, 1912-1982, eds. Miriam Cohen and Jo Anne Rousso, Montgomery, Alabama, 1982, p. 11.

40. Kerem, supra, at p. 373-74.

41. Montgomery City Directory, 1910.

42. Montgomery City Directory, 1910.

43. Entry for Ephraim Taranto, 1910 Census, supra.

44. Entry for Ephraim Taranto, 1910 Census, supra.

45. This Taranto, whose relationship to us is unknown today, might have been a cousin.

46. Montgomery City Directory, 1911.

47. Montgomery City Directory, 1912.

48. Montgomery City Directory, 1913. This “Joseph Capouya’s” identity is unclear. Leah’s father Raphael Capouya had a brother Joseph, but he is not known to have come to America. Leah's uncle Joseph (or Haim) had a son Rahamin Capouya who did immigrate to America, living out his life in New York City. Rahamin’s son Joseph, a young man by 1913, could be the same “Joseph Capouya.”

49. Montgomery City Directory, 1913.

50. Montgomery City Directory, 1913.

51. Bension's citizenship is noted as "1912 al” (an alien immigrating in 1912), a year later than the actual date. Alien status and 1912 immigration are also noted for Leah and the Taranto children.

52. U.S. Census Records, 1920, State of Georgia, City of Atlanta.

53. Obituary of “Leon Benson Taranto,” Atlanta Journal, May 2, 1950, page 33; “Leon Taranto, 92, Dies; Rites Today,” Atlanta Constitution, May 2, 1950, page 22.

54. “Mrs. Taranto’s Rites Sunday,” Atlanta Journal, July 29, 1950, page 9; “Funeral Notice of Mrs. Leah Taranto,” Atlanta Constitution, July 29, 1950, page 14.

55. Abraham was tested by the Almighty’s call to sacrifice his son Isaac. Centuries later, the Egyptians lamented the tenth plague that struck down the first-born son of each household, and King David mourned the death of Absalom, the son who had betrayed him.

56. “Girl, 22, Dies at Grady After Drinking Poison,” Atlanta Constitution, March 4, 1933, page 1.

57. U.S Dept. of Labor, Naturalization Service, Declaration of Intention of Abraham Taranto, No. 2237, United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia (Atlanta), April 13, 1925.

58. U.S Dept. of Labor, Naturalization Service, Declaration of Intention of Ephraim Taranto, No. 2342, United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia (Atlanta), June 2, 1926.

59. Under Turkish rule since 1430, Salonica became the world’s most Jewish metropolis. By 1905, its 120,00 inhabitants included 75,000 Jews, almost all Sephardim. “Salonica,” The Jewish Encyclopedia - A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Times to the Present Day, Funk & Wagnalls, 1905, vol. 10, pp. 658-59. Five years after the 1912 annexation, a fire devastated the city, leaving most Jews homeless. The city’s Jewish character further deteriorated as the new Greek rulers settled 100,000 Greek refugees in Salonika, to Hellenize the city. The Jewish population dwindled to about 56,000 by the outbreak of World War Two. In 1943, the Germans deported virtually all the remaining Jews to the Nazi death camps and destroyed most remaining signs of this ancient community. After the war, Salonika Jewry included no more than about 2,000 survivors. Ruth Porter and Sarah Hare-Hoshen, Odyssey of the Exiles - The Sephardi Jews 1492-1992, Beth Hatefutsoth and Ministry of Defence Publishing House, 1992, p. 131.

60. John and Elizabeth Romer, The Seven Wonders of the World - A History of the Modern Imagination, Henry Holt & Co., New York, 1995, pp. 34-35. Another historical account dates the building of the Colossus to 302 B.C.E. and its destruction to 227 B.C.E. Isaac Jack Levy, Jewish Rhodes: A Lost Culture, Judah L. Magnes Museum, Berkeley, 1989, p. 12.

61. Romer, The Seven Wonders of the World - A History of the Modern Imagination, supra, pp. 34-35.

62. Franco, The Jewish Martyrs of Rhodes and Cos, supra.

63. “Turkey,” The Jewish Encyclopedia, vol. 12, pp. 279-91, cites a 4,000 figure, while other sources have suggested up to about 5,500.