Interview with Ruth Behar1

Her Life, Her Writing, Her Application for Spanish Citizenship

Interviewed by Judith Roumani2

JR: Thank you so much for granting us this interview. I’d like to ask you a few questions about yourself, your life, your writing, about your application for Spanish citizenship, and your upcoming novel, Across So Many Seas. All of these questions, I am sure, relate to personal identity, and I hope a picture of you and what you believe in will emerge. My first question is, could you tell us the rough outlines of your story, starting back in Cuba.

RB: My maternal grandparents, Baba and Zeide, were Ashkenazi Jews from Poland and Russia and my paternal grandparents, Abuela and Abuelo, were Sephardic Jews from Turkey. All four found their way to Cuba in the 1920s. They married and formed families and became part of the Jewish community on the island. Baba and Zeide lived in a rural town called Agramonte in the province of Matanzas and my mother lived there as a little girl. They were the only Jewish family in the town. Eventually they moved to Havana and opened up a lace store on Calle Aguacate; their apartment was right above the store. Abuela and Abuelo lived nearby on Calle Oficios and Abuelo worked as a peddler. The Ashkenazi and Sephardic communities kept separate and so it was unusual when my parents started dating.

Despite the cultural clashes, my parents married. I was born in Havana and spent the first years of my childhood there. I briefly attended the same school my mother had gone to, the Colegio Hebreo Autónomo, where instruction was in Spanish and Yiddish. When I was four and a half, my parents and my brother and I left for Israel, and a year later we settled in New York. Nearly all of our family chose to leave Cuba after the revolution in 1959 and start a new life in New York. My mother’s older sister, Sylvia, had married an American Jew and they lived in Queens, so we went to live there, in an apartment in the same building as them. The first few years in Queens we had a vertical home: my maternal grandparents lived on the third floor, my Aunt Sylvia and uncle and cousins lived on the fourth floor, and my parents and brother and I on the sixth floor.

JR: Did your father’s family always know they were from Spain? How did they express this, and what impact did it have on you as a child? And I understand your mother’s family is from Poland, so your parents had a mixed marriage, and how was this viewed?

RB: My father’s family was certain of their Sephardic identity and knew that long ago they came from Spain. This identity was expressed in their use of Ladino, which gradually mixed with their Cuban Spanish. And my Abuela had played the oud as a young woman and sang in Ladino. As a child, what I knew is that the Spanish spoken by Abuela and Abuelo sounded like sweet music, and that they didn’t speak Yiddish, as did my maternal grandparents, Baba and Zayde. On Passover, we could go to the home of Baba and Zeide the first night and to the home of Abuela and Abuelo the second night, and the cuisine of each was so distinctive – gefilte fish and matzoh ball soup on the first night, and egg-lemon soup and stuffed grape leaves on the second night. I knew that each set of grandparents had a different culture, but it wasn’t until I was older that I called those cultures “Ashkenazi” and “Sephardic.” My Ashkenazi family referred to my father as “turco,” as Turkish; the “otherness” of his background was often pointed out. He was temperamental, and this seemed to them to be a “Sephardic” characteristic.

So, yes, in a certain way, my parents had a mixed marriage, or an “intermarriage.” My Ashkenazi family couldn’t understand how my father could be Jewish and not speak Yiddish. My Sephardic family, in turn, spoke Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) and that was a Jewish language to them. And yet eventually this conflict would be resolved in an unexpected way, when they all left Cuba after the revolution in 1959, and the language they then spoke in the United States was Spanish, because they missed the island so much, and their Cuban identity became stronger in exile.

JR: How did you carry this identity as a teenager, and as a college student?

RB: Growing up in New York, I always had to explain how it was possible for me to be both Cuban and Jewish. It seemed an odd identity to most Americans. I usually didn’t go into too much detailed, explaining that I was also Ashkenazi and Sephardic, not to make things even stranger. In college, I started to explore these different layers of my identity, and to read about Jewish history and Cuban history. Later on, I formed part of a group of writers examining Jewish Latina/Latino culture and literature, and then from there, I went on to seek an understanding of my Sephardic heritage. I was drawn to Spain already in my teens, and while in college, I spent a semester abroad in Madrid and returned and directed a performance of García Lorca’s La casa de Bernarda Alba. In those years, I also played Spanish classical guitar. Afterwards, I went on to do anthropological research in a small village in northern Spain. Though I didn’t study Sephardic topics in those early years in Spain, I was always aware that part of my heritage was Spanish and that I had roots in that land, and I went several times to the beautiful and haunting Museo Sefardí in Toledo, once a fourteenth-century synagogue, which inspired an interest in the Jewish presence in Spain.

JR: When did you first start writing, and what reactions did you get? They must have been positive, as you have been incredibly productive. How many books is it?

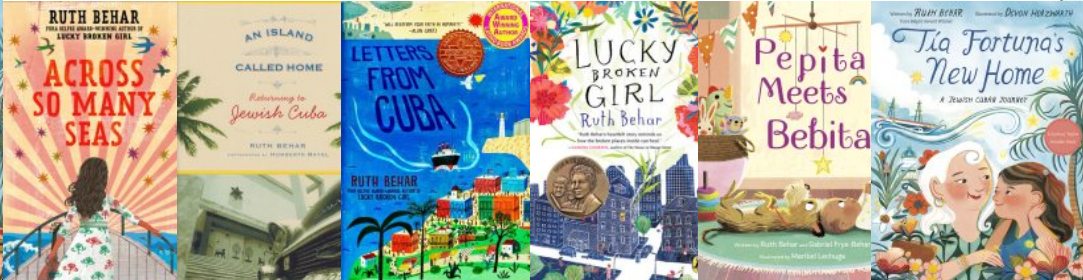

RB: I started writing when I was a teenager and kept a notebook with comments on books I had read and also wrote many drafts of poems. I had a Cuban-American high school teacher, Mercedes Rodríguez, who inspired me to write in Spanish too. I wouldn’t say that all the reactions were positive when I started writing. The first book I wrote was The Presence of the Past in a Spanish Village, based on my dissertation, and it was well-received in the anthropology community. Eventually, it was published in Spanish and I was glad to be able to share it will the children and grandchildren of the people who’d shared stories of their lives with me in the village. From there, I went on to write about Mexico, Cuba, and other places. I’ve written five books about my travels. One book that might especially interest your readers is An Island Called Home: Returning to Jewish Cuba, which is based on my travels around the island and offers a chronicle of the Jewish people I met and the stories they shared with me. I’ve edited and co-edited four books about anthropology, and Cuban literature, art, and culture. In recent years, I’ve been writing fiction for young people. I am the author of two young adult novels, Lucky Broken Girl and Letters from Cuba, and two picture books for younger children, Tía Fortuna’s New Home and co-authored with my son, Pepita Meets Bebita. All these books are also available in Spanish. I’ve also written many essays and articles, as well a bilingual book of poetry, Everything I Kept/Todo lo que guardé. And I’ve made a documentary, Adio Kerida/Goodbye Dear Love, about the Sephardic Jews of Cuba.

JR: I identify with Tia Fortuna, as I also have lived in Surfside at the same time, and I watched the demolitions, though I only lived there for two years. I remember the Seaway, too. I have the impression that nothing in Florida lasts very long, there are always contractors with more grandiose ideas, who uproot little old ladies.

RB: That’s amazing, all the ways that you connect to the story of Tía Fortuna. I also got to know The Seaway. I had a friend who lived there and I was so drawn to this building next to the sea that I decided to set my book in that place. Now the new building is almost done and I’m glad I was able to offer a tribute to The Seaway and its charms.

JR: What prompted you to apply for the Spanish or Portuguese citizenship, which one was it, and when was this?

RB: I began the process, but in the end I didn’t complete my application for Spanish citizenship. The pandemic came in 2020 and it interrupted the process because I couldn’t travel to Spain to sign the documents, as is required. I decided to put the application aside for the time being. I may try again perhaps, if there’s another opportunity in the future.

JR: I understand you have an upcoming novel, Across So Many Seas. Could you kindly tell us a little about it?

RB: I wanted a really broad canvas for Across So Many Seas and thought of telling a story of four girls, in four different times, in four different places. These were the first notes I wrote to myself:

In each generation, a twelve-year-old girl is caught in the web of history:

Something all share – the dream of a just, tolerant world…

The words of a lost song…

A need to forgive…

The bonds of family…

And a heritage of seeking freedom that goes back five centuries to Spain…

The four girls, Benvenida, Reina, Alegra, and Paloma, each have a story to tell and the novel traces their journeys, with their families, through different historical periods and places. The novel begins in Spain in 1492, on the eve of the expulsion, then jumps to Turkey in 1923, just as Ataturk is declaring Turkey a Republic. It then crosses the ocean to Cuba in 1961, in the first years of the revolution, and ends in Miami, Florida in 2003, bringing the story near to the present day. The protagonists are Sephardic Jews who take pride in their Spanish heritage and stay connected to their history through the memories of the songs their ancestors sung. Each of the girls is on the cusp of young adulthood and learning how to use her voice and find courage in challenging times. The novel explores their search for home as each experiences displacement. In the end, Paloma, visiting the Museo Sefardí in Toledo, Spain, with her family, finds a path to an understanding of the profound loss experienced by their ancestors expelled from Spain in 1492.

1 Ruth Behar is a Cuban-American anthropologist and children's author, and the winner of MacArthur and Guggenheim fellowships.

2 Judith Roumani is the editor of Sephardic Horizons.

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800